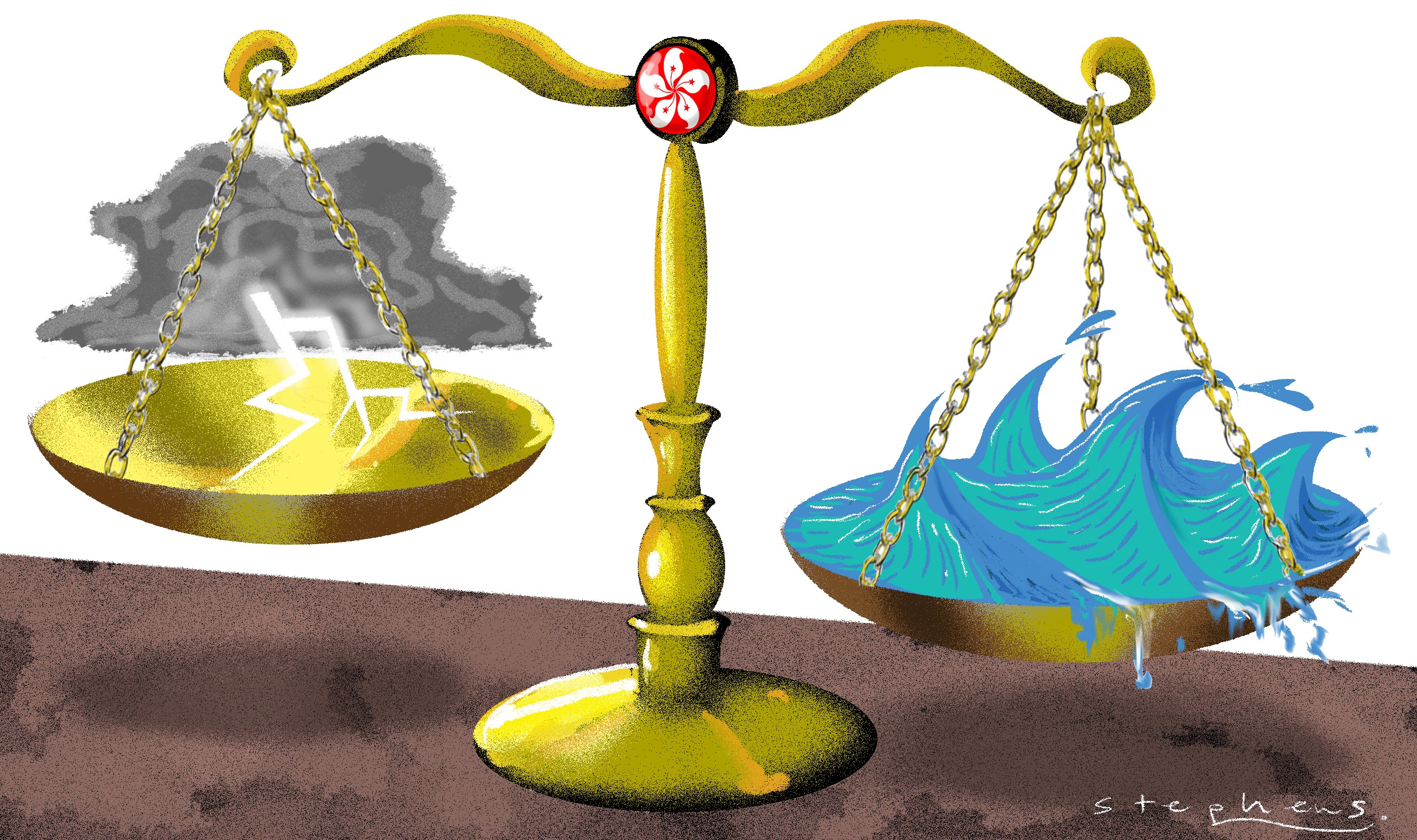

The UN’s top human rights body has sharply criticised Hong Kong’s application of the national security law, making it clear basic freedoms and the rule of law are in danger. Rather than trotting out tired responses, the government should take the criticism to heart and repair Hong Kong’s reputation before it is too late.

Under the standard applied, any slogan that might bear a meaning that is prohibited could be judged unlawful. Pursuing the charge of causing grievous bodily harm would have been supported by the evidence and not caused fears over human rights in Hong Kong.

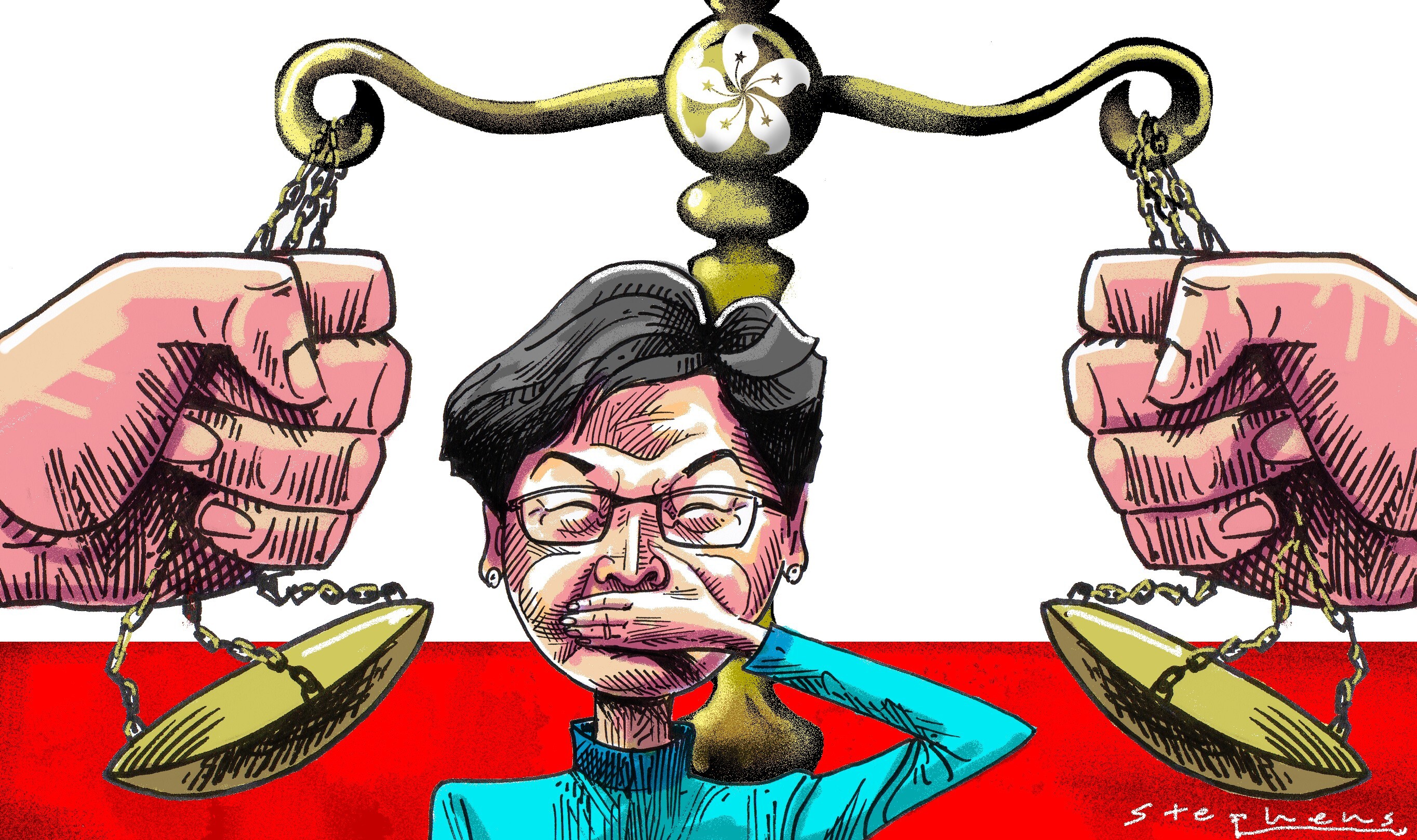

In acknowledging the division of labour between the branches of government, with checks and balances among them, Lam has defined Hong Kong’s separation of powers.

We are told Beijing must act because Hong Kong failed to fulfil its duty under Article 23 to enact such laws ‘on its own’. But why was a bad bill proposed in 2003 and an opportunity for reform squandered?

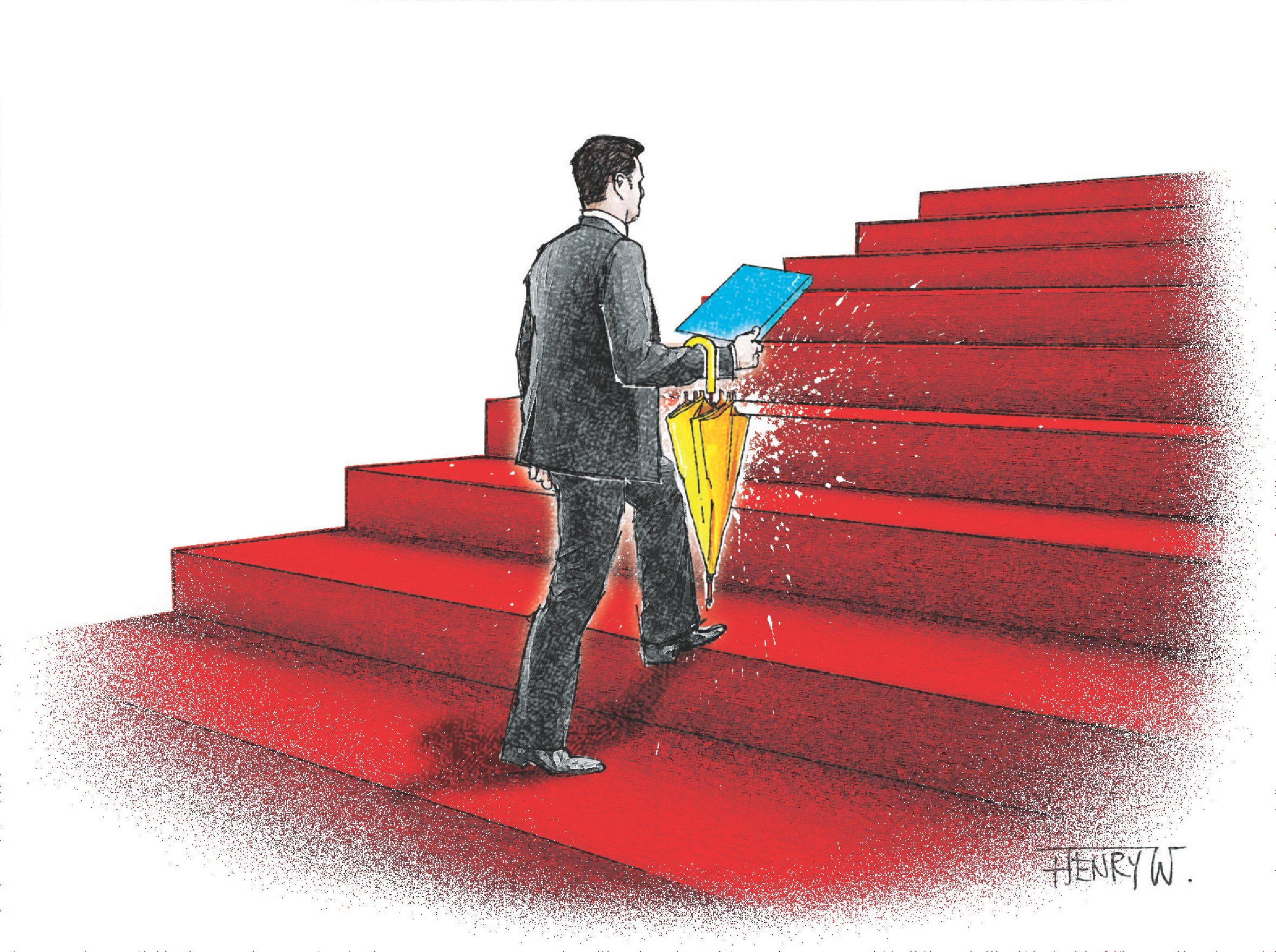

From its process of enactment, apparently bypassing the local legislature and ignoring public opinion, to its future implementation and enforcement, the national security law is incompatible with the city’s common law tradition.

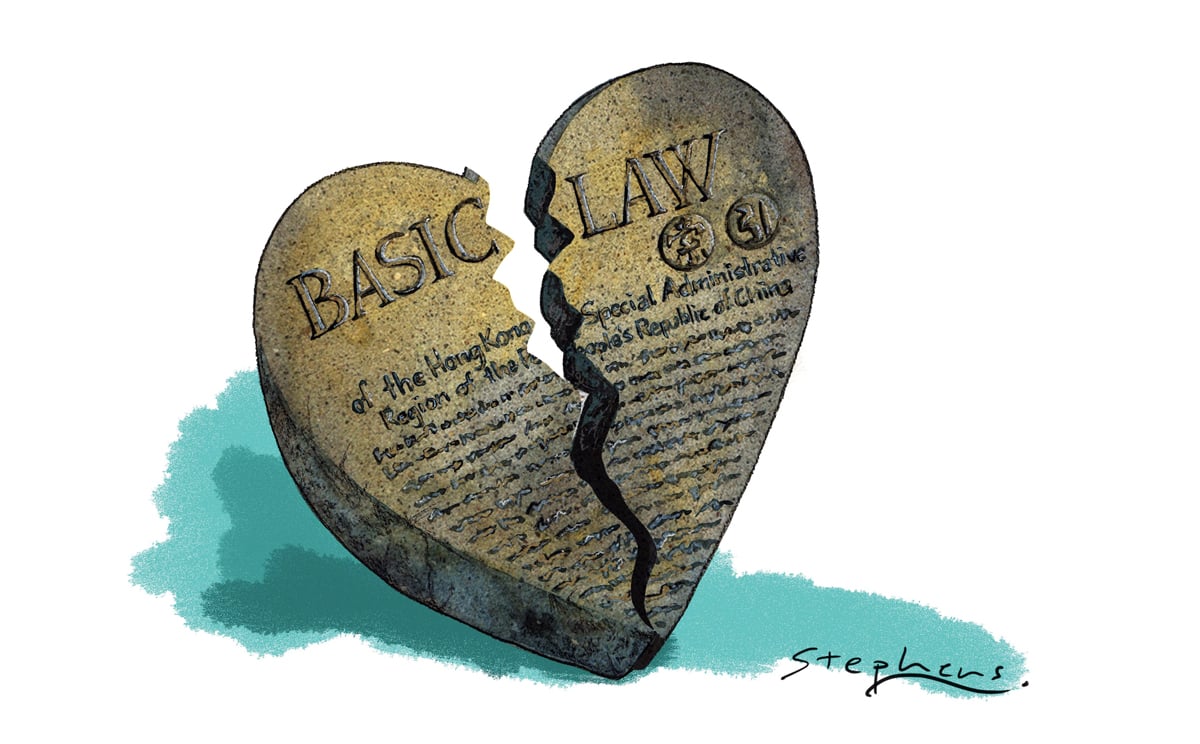

If the Basic Law’s restraint on mainland departments interfering in local affairs does not apply to offices of the central government in Hong Kong, what is the point of the mini-constitution?

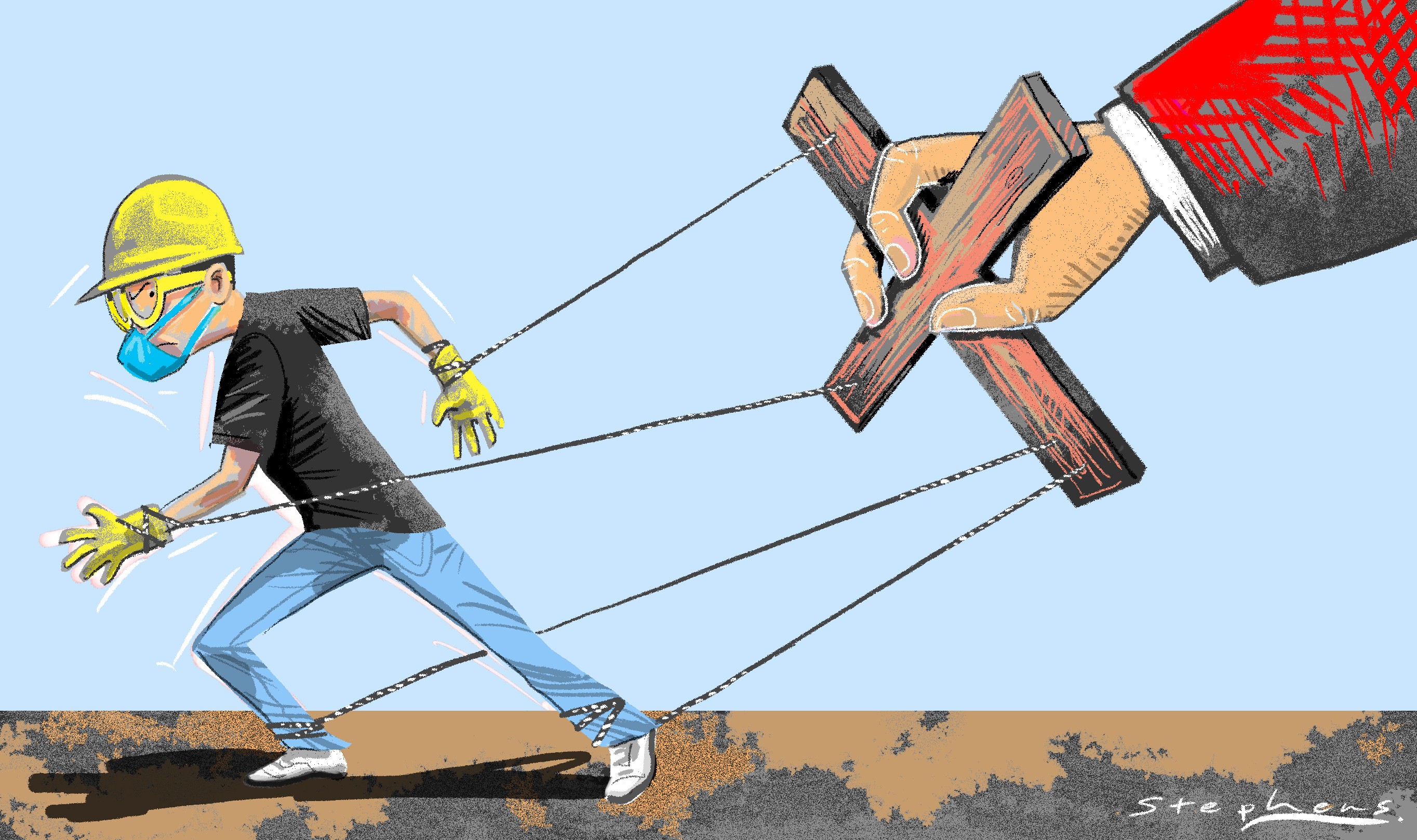

Lack of autonomy is at the heart of protests past and present. A democratically elected government would be better placed to safeguard this, convey the city’s concerns in terms that are palatable to Beijing and end the protests.

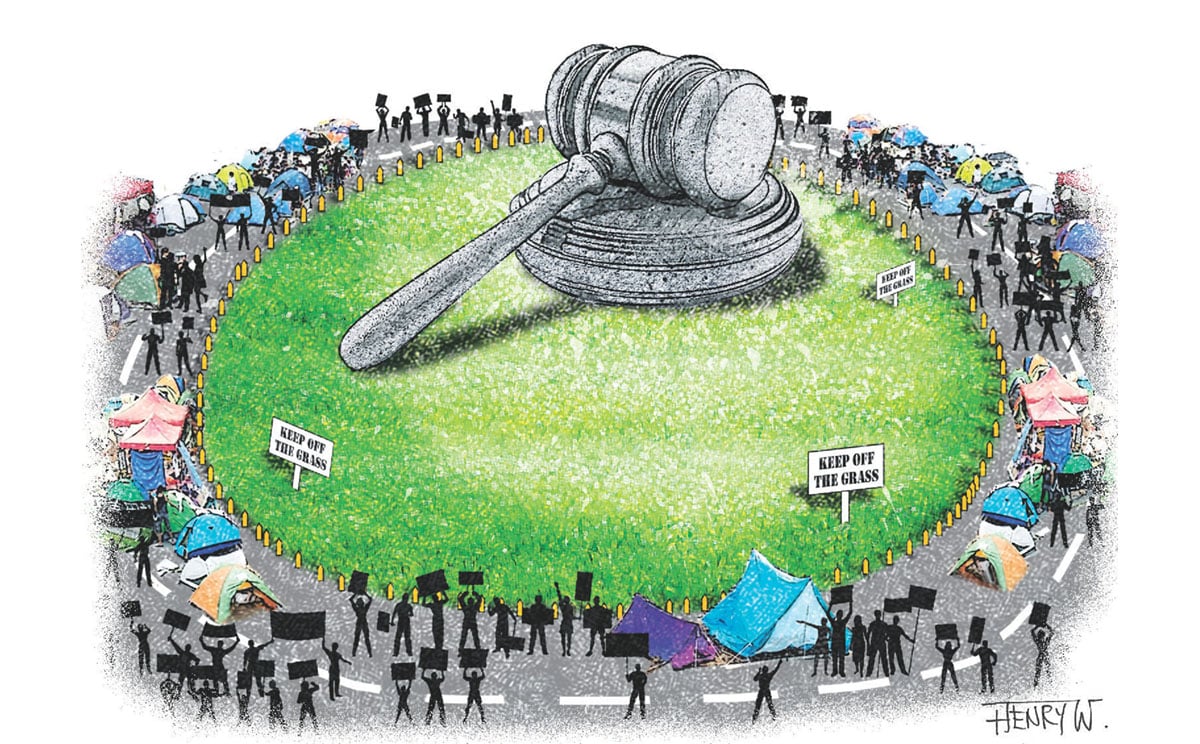

The rule of law is not about enforcing government diktat. It is about the impartiality and independence of courts and leaders, which protesters fear are being eroded.

In this and other mass rallies since 2003, Hongkongers are rising up in defence of their rights and freedoms only because their government can’t – or won’t – find its voice to defend the city’s core values against pressure from Beijing.

The repeated dismissals of the relevance of the Sino-British Joint Declaration are unsettling, particularly as there is no question the document is a treaty under international law, and binding on its signatories.

Michael Davis says the Hague ruling uncovers livelihood issues and environmental damage that China should attend to, if it is to change course and repair its reputation

As court orders, followed by more aggressive police tactics, seek to clear the streets in Mong Kok and Admiralty, the non-violent civil disobedience campaign in Hong Kong has reached a climax.

A small group of lawyers has added to the chorus of establishment figures denouncing the Occupy movement as undermining the rule of law. Are they right?

Hong Kong protesters have recently been under attack by prominent Beijing officials and the state media for allegedly violating the rule of law and for making democracy proposals that are said to violate the Basic Law.

Hong Kong people and the media are surely wondering whether anything positive can come out of the proposed democracy negotiations.

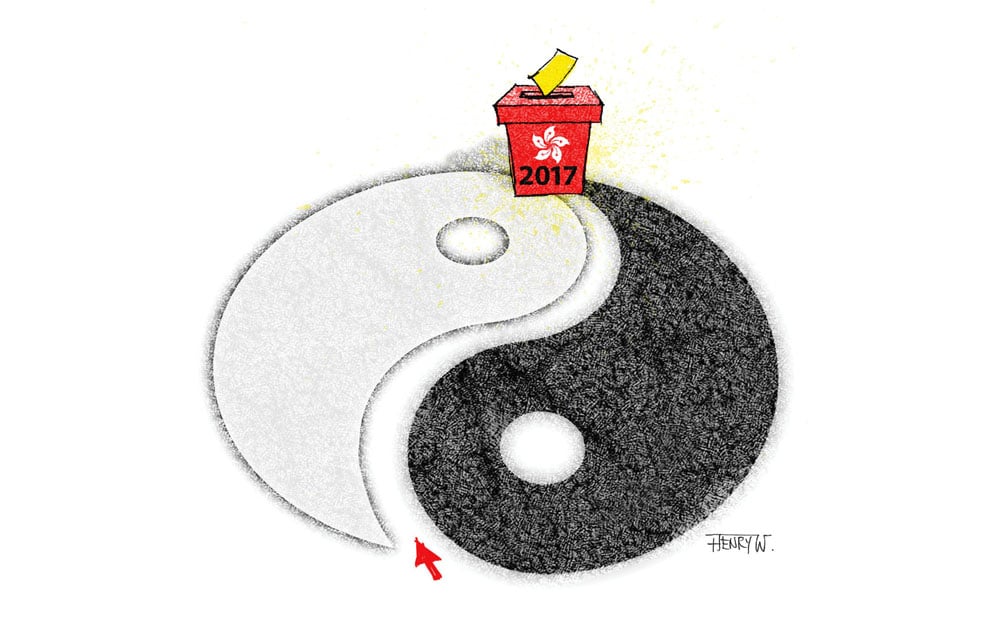

Beijing's decision on universal suffrage marks a dark day in Hong Kong history. The shortcutting of its firm commitments in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law signals a broken trust.

Reading between the lines of the consultation report and Leung Chun-ying's report to the National People's Congress Standing Committee, it seems clear that the government has all but decided in favour of a non-democratic model for the chief executive election.

What is the purpose of Beijing's white paper on Hong Kong? Some argue that it is issuing a warning to unruly protesters. Others assert that this is nothing more than a progress report on "one country, two systems".

As the consultation over the method for selecting the chief executive in 2017 comes to an end, there is a need to evaluate various proposals. Much of the discussion has focused on what Beijing will or will not accept.

Dear chief secretary, considering your frequent calls that proposals for nomination of the chief executive conform to the Basic Law, and mindful that the Basic Law also requires conformity to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, I offer the following proposal.

The government has argued that civic and party nominations of chief executive election candidates being promoted by the democratic camp are contrary to the Basic Law. Both the chief secretary and the secretary for justice have based this view on what they argue is the plain meaning of the Basic Law text.