To fight sleaze, Xi needs to call the Untouchables

It won't be politically painless but China's new leaders can stop the official rot, just as other countries have done on the road to development

The pledge by China's new leaders to stamp down on official corruption has been greeted at home and abroad with weary cynicism.

People have heard similar pledges too often before. Too often the subsequent campaigns have been little more than window dressing, or a pretext to eliminate political rivals. A handful of corrupt officials have been imprisoned, or even shot, but official corruption has continued unabated.

Many believe this time will be no different. The sceptics point to international media articles detailing the vast fortunes amassed by the families of top-tier officials and to the recent crackdown on China's domestic press as evidence that the country's new leaders have no interest in a real clean-up.

Getting rid of a few bent officials will change nothing, the sceptics lament. Others will simply step into their shoes. It is the system itself that is corrupt.

Some even look at history and suggest there is something in China's culture that encourages corruption - which always involves a transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich, and from the weak to the strong. Change, they conclude, is all but impossible.

Although such pessimism is understandable, it is unjustified. Corruption may be rampant in China, but there is nothing exceptional about that - or incurable.

Developed countries now considered relatively clean-handed, like Britain or the United States, also went through phases of deep sleaze while their economies were growing fast.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries official corruption was endemic in Britain. Changing things took decades, and huge political upheavals. But eventually the rot was excised.

Similarly, during its period of rapid growth between 1870 and 1930, the US was also awash with political corruption.

In the 1870s senior politicians colluded with distillers to under-report whiskey sales, siphoning the foregone tax revenues directly into the coffers of the ruling Republican Party.

Things hadn't improved much by the 1920s, when the Secretary of the Interior was jailed for taking bribes and the prohibition of alcohol fostered a countrywide culture of corruption.

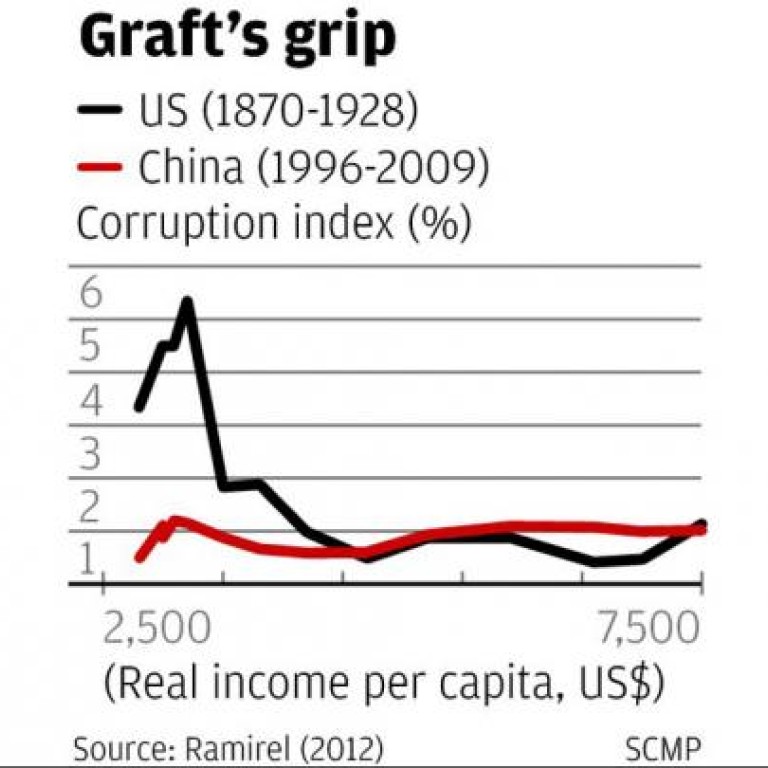

China today looks no worse. In an attempt to compare historical US sleaze with contemporary Chinese corruption, Carlos Ramirez at George Mason University has compiled an index for each.

For the US he counted the number of articles in five major American newspapers between 1870 and 1930 that referred to US government corruption, divided by the number of articles about politics. Then he repeated the process - using the same five US papers - for China between the late 1990s and 2011, the period when Chinese incomes per head were at comparable levels.

Clearly there are some weaknesses with this method. For example, you might think US newspapers would be more likely to report local corruption than Chinese sleaze.

But Ramirez, rejects this suggestion. Employing Britain's newspaper as a control, he finds little evidence of domestic bias.

On the contrary, he argues that, if anything, US newspapers are inclined to over-report Chinese corruption as part of a China-bashing agenda.

On the other hand, he doesn't recognise that the rising incidence of corruption he detects in China over the last two decades may be the result of more and freer media coverage rather than of greater sleaze. And he fails to acknowledge that the true level of corruption in China may still go under-reported because of enduring constraints on both local and international media operating there.

Still, to a certain extent those objections cancel each other out, leaving the conclusions Ramirez draws still standing.

He reckons that in 2009, when Chinese incomes per head were US$7,500 (in real 2005 terms), China's incidence of corruption was much the same as America's in 1928, when incomes stood at the same level (see the chart).

That's encouraging. Admittedly, corruption on the scale of the US in 1928, when violent gangster Al Capone effectively ran Chicago, then America's second-largest city, is nothing to smile about.

But the US largely dealt with its problem over the following decades. China can too, although the process will inevitably involve a great deal of political pain.

So if incoming president Xi Jinping wants to overcome the cynicism and really tackle official corruption, perhaps what he needs is a Chinese version of Eliot Ness and his squad of Untouchables to clean up the corridors of power.