Tsang's budget will do nothing to solve Hong Kong's twin problems

Despite city's rude fiscal health, a structural glut of government cash and sky-high property prices are two sides of the same coin

Tomorrow Financial Secretary John Tsang Chun-wah will stand up to deliver his sixth budget speech.

The finance ministers of most developed economies would be green with envy at the strength of Tsang's position.

In his speech he is likely to announce an economic growth rate for last year of around 1.5 per cent. That might not sound very impressive. But with much of the developed world struggling to escape recession, it counts as a robust performance.

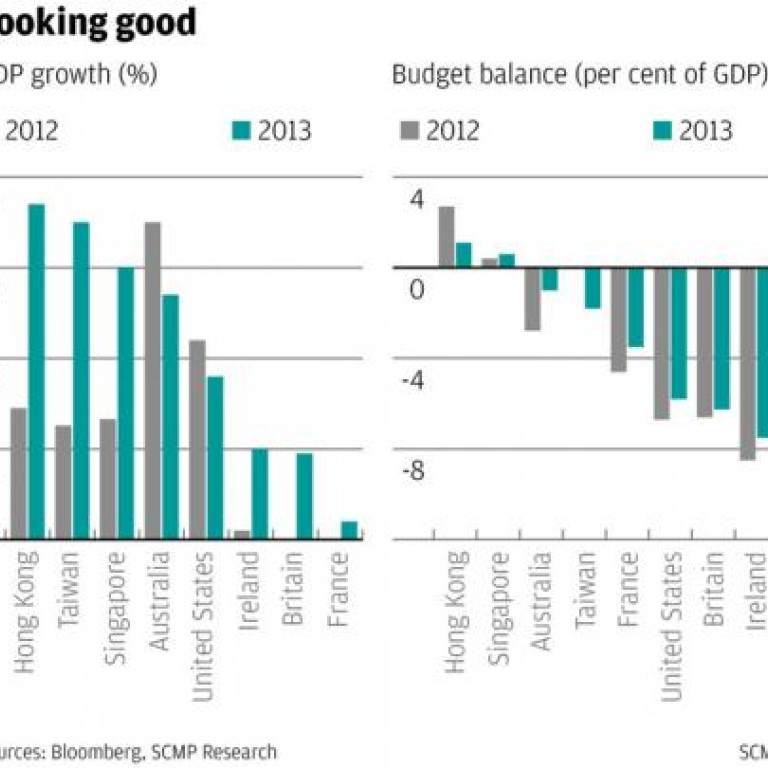

Even better, as the first chart below shows, Hong Kong's economy is forecast to grow by almost 4 per cent this year, which marks the city out as one of the strongest rich economies around. At the same time, unemployment is low at just 3.4 per cent, while inflation remains muted at 3 per cent.

And almost uniquely outside the oil-exporting sheikhdoms of the Persian Gulf, Hong Kong's government finances are in rude health. Last February Tsang forecast that the government would run a deficit for the 2012/2013 fiscal year of HK$3.4 billion.

In reality, by the time all the receipts are counted, the government is actually likely to be in the black to the tune of HK$55 billion, or around 2.7 per cent of the city's gross domestic product (see the second chart).

What's more, last year's surplus was no one-off windfall. Despite riding a violent economic roller-coaster over recent years, the current fiscal year will be the ninth in a row that the city's public finances have been in the black.

As a result, while most developed economies are labouring under the shadow of ever-growing debt mountains, Hong Kong has amassed a stash of excess reserves worth around HK$1.4 trillion, or 70 per cent of the city's annual output; a clear sign that the surplus is structural in nature and not cyclical.

Yet although he delivers his budget from a position of enviable strength, Tsang is a troubled man. His biggest worry is Hong Kong's fast-rising home prices; a problem so acute he could not even wait for tomorrow's budget to reveal a doubling of stamp duties on property transactions, jumping the gun with an announcement last Friday.

Whether higher stamp duties will do anything to make homes more affordable is doubtful. If anything the punitive tax rate is likely to deter sellers, reducing supply even further.

In short, the stamp duty increase looks like a knee-jerk reaction from a government desperately short of ideas.

Yet if Tsang and his officials had stopped to think about it, they would have realised that the strength of their position and the biggest problem they face - a structural glut of government cash and sky-high property prices - are two sides of the same coin.

The government runs a structural surplus because it long ago adopted a high land price policy, restricting the supply of new building land in order to bump up its revenues from developers paying to convert land zoned for industrial or agricultural purposes to residential use.

And home prices are unaffordable today for exactly the same reason: the government operates a high land price policy in order to generate fat revenues from the property market.

Clearly the solution to both problems - an unneeded structural surplus and prohibitively expensive housing - is not to tinker with stamp duties. The solution is a root and branch reform of the way the market for building land in Hong Kong works.

Unfortunately, that's far too much to hope for in tomorrow's budget.