'Made in America' means added pain for Hong Kong

City could lose its regional cost advantage as cheaper fuel and fresh investment help bring the US dollar - and the HK dollar - back to life

For the past 10 years, Hong Kong's economy has been boosted by twin external superchargers.

Now, both are in danger of breaking down.

Part of the performance boost over recent years was provided by the rapid growth of China, which yielded a bonanza for the city's financial, trade services and retail sectors.

But Hong Kong also got a propellant charge from its exchange rate peg to the US dollar.

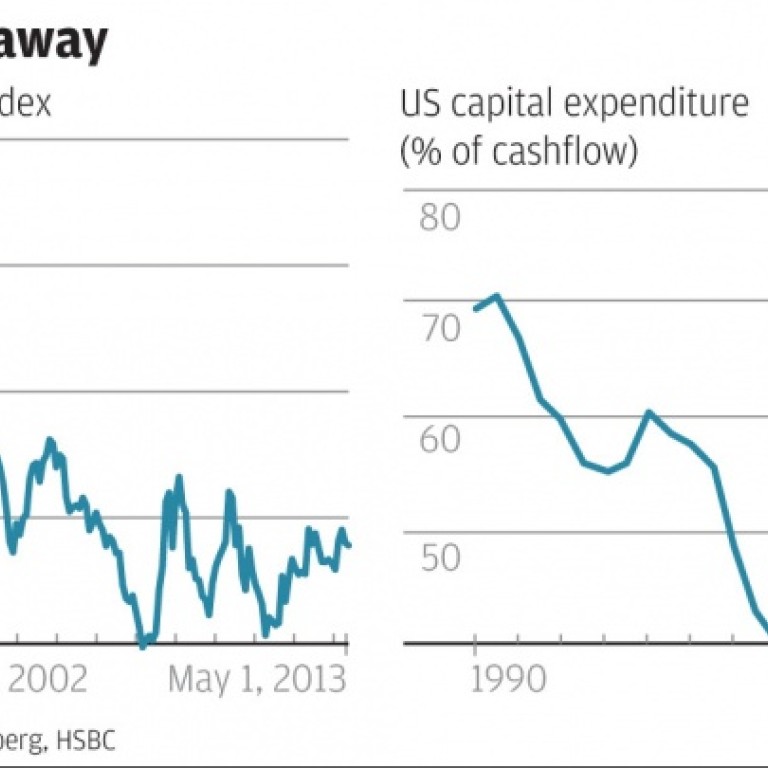

Since 2002, the US dollar has lost a third of its value against a basket made up of the currencies of its trading partners and competitors (see the first chart).

Because of the peg, the Hong Kong dollar has also declined in value. Since 2002, it has fallen by almost a quarter against its own trade-weighted basket of currencies; a fall that's sharply enhanced the city's competitiveness.

Sure, some of the competitive gain was offset by the steep rise in Hong Kong's property prices over the same period.

But only some.

Thanks to currency depreciation, Hong Kong won a powerful cost advantage relative to its Asian neighbours, which helps to explain why the city has outperformed Singapore in terms of real output growth per head over recent years.

Now, ominously, Hong Kong's twin turbines may be about to run out of gas.

First, as even the China's-going-to-take-over-the-world brigade now recognise, the mainland is shifting to a structurally slower growth trajectory.

Second, the US dollar, long regarded by many as a currency in terminal decline, looks as if it could be primed for an extended period of appreciation.

Three related factors are likely to drive the US dollar higher.

First, the US currency's long decline, coupled with flat local currency unit labour costs over recent years and the boom in cheap domestic shale gas, means the US has clawed back much of its own lost competitiveness.

As a result, US companies are no longer "offshoring" jobs to cheaper countries in Asia.

Given the restored cost advantage, many analysts believe they will soon begin "onshoring"; taking advantage of their low leverage levels to invest in new factories at home rather than abroad.

Such a revival in manufacturing - and in a report yesterday HSBC noted rising capital expenditure across a range of US industries (see the second chart) - should further reduce the US trade deficit, which has already fallen by 30 per cent since the crisis.

That will directly support the US dollar, but according to Hans Redeker, a foreign exchange strategist at Morgan Stanley in London, it will have a second, indirect, strengthening effect.

Fresh investment at this point in the cycle, he argues, will raise US productivity, which in turn will attract capital inflows, further boosting the US dollar in a positive feedback loop similar to the inward investment surge of the late 1990s.

Finally, any strengthening of the US dollar will prompt investors to abandon it as a funding currency for carry trades in favour of the yen.

Such a switch - already emerging as a result of Tokyo's new-found enthusiasm for reflating the Japanese economy - would remove a powerful downward force weighing on the US dollar, providing further impetus to appreciation.

It's early days yet, but where the US dollar goes, Hong Kong's pegged currency must follow.

That could prove painful. Between 1995 and 2002, the US dollar appreciated by almost 50 per cent on the back of the US inward investment boom.

As a result, Hong Kong's competitiveness was severely eroded. When the Asian crisis hit, the city found itself forced to readjust through a long period of low growth and deflation. Over the coming years, history may be about to repeat itself.