Why the HKMA should fret over consumer debt

The coming housing crisis in the city after the Fed raises US interest rates is going to plunge many Hongkongers into negative equity

Only last week my esteemed colleague Jake van der Kamp was complaining that there is altogether too much consensus among the columnists. Commentators are not meant to be a harmonious society.

Well, Jake, you've got your wish for a healthy dose of adversarial scrappiness, because today the back page is going to pick a fight with the front page.

In his column today, Jake pours a bucket of cold water over the boss of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Norman Chan Tak-lam, who warned last week that Hongkongers were in danger of trying to live beyond their means.

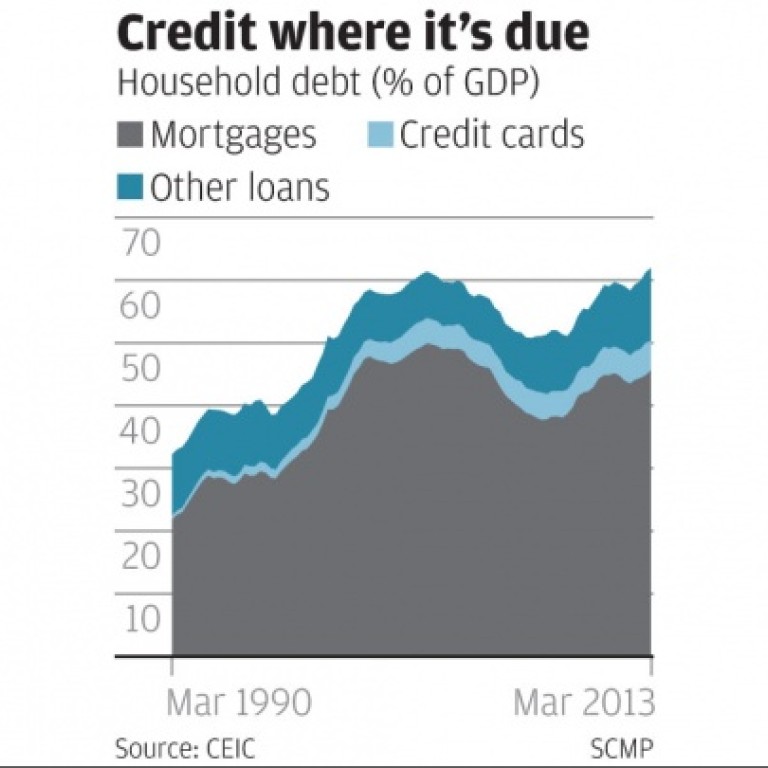

Among other things, Chan is worried that private consumption is growing faster than incomes, and that the city's level of household debt is rising, climbing to 61 per cent of Hong Kong's gross domestic product.

Jake takes issue with this warning, pointing out that debt is a stock measure while GDP measures flow. Over recent years, he points out, household debts have actually declined as a proportion of total loans.

I am not so sure he should dismiss the debt-to-GDP measure so lightly. After all, the ratio of a country's household debts to its national income clearly affects its people's ability to service those debts.

Even so, compared with other developed economies a 61 per cent debt to GDP ratio is hardly excessive. It puts Hong Kong on a par with the frugal Germans, behind Japan or South Korea, and well below wastrels like the Americans, now on 85 per cent, and the British, whose household debts stand at 90 per cent of GDP.

What is more, I don't buy into Chan's assertion that debt has risen because of a credit-fuelled consumption binge. As the chart shows, three-quarters of the rise in Hong Kong's household debt over the past five years consists of the increase in mortgage debts. Mortgage debts, naturally enough, have risen because homes have got more expensive, while mortgages are cheap.

That does not mean we can relax, though. On current trends in US unemployment, at some point around the end of next year, the United States will begin raising interest rates.

That will mean dearer mortgages in Hong Kong, and very likely a major correction in the local property market.

Granted, thanks to modest leverage levels among home loan borrowers, the correction would have to be really big to push many families into negative equity, where the size of their mortgage debt exceeds the value of their homes.

According to estimate, if prices fell by a third, putting them back where they were in mid-2010, only around 1,000 families would find themselves under water.

But if prices were to fall by half, dropping back to their January 2009 level, the number of borrowers in negative equity would soar to almost 60,000.

Many market-watchers are sanguine at this prospect, pointing out that almost twice as many households fell into negative equity at the bottom of the last big slump in 2003, when prices fell by two-thirds.

But even at the worst of that bear market the proportion of borrowers who got more than three months behind with their payments never climbed above 1.5 per cent.

That sounds reassuring, but alas, there is a crucial difference between that correction and the one that is coming.

Last time around, the property market crashed at a time of falling interest rates. Between the height of the bubble in late 1997 and the depths of the slump in 2003, the US Federal Reserve spent most of its time in easing mode.

HSBC's prime lending rate, the benchmark for local mortgages at the time, duly followed, falling from 9.5 per cent to just 5 per cent.

As a result, the cost of servicing a mortgage relative to household income tumbled, which meant that few households defaulted on their payments, even though the number in negative equity shot up to more than 100,000.

Next time around, the interest rate environment will not be so benign. Today, with home loans available at interest rates of just 3 per cent, the cost of servicing a mortgage typically eats up around half of household income.

When the Fed begins raising interest rates, that cost burden is going to rise, plunging many families into financial hardship - and some into default.

As a result, Norman Chan is right to be concerned about household debt levels. And Jake, admirable chap though he is, is wrong.