To get rich, poor states must ignore the Washington rule book

A new book argues that in East Asia, there are nations that protect their industries and prosper and those that heed others' advice and fail

The line of latitude at 20 degrees north neatly bisects East Asia.

Skirting Thailand's northern border, and passing eastward between the Philippines and Taiwan, it divides the region into two distinct economic zones.

To the north, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan - three places that long ago achieved developed-country wealth levels. More recently, China has emulated their development, stunning the world with three consecutive decades of rapid growth.

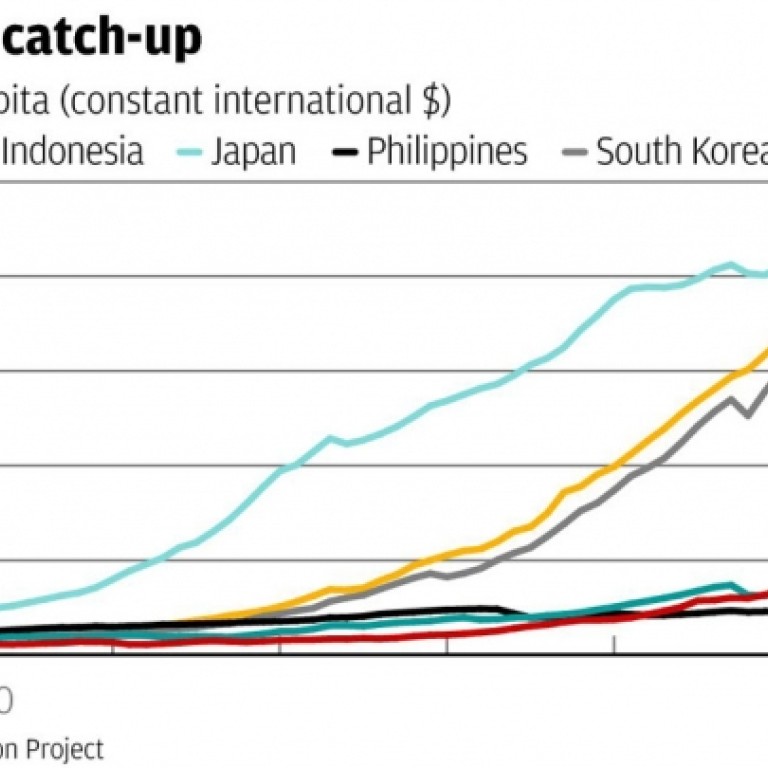

South of the 20th parallel, however, economic development has lagged behind. Although in 1950 Indonesia and the Philippines boasted similar incomes per head as Korea or Taiwan, today their levels of gross domestic product per capita - even after adjusting for differences in purchasing power - are less than a quarter of those enjoyed by their northern neighbours (see chart).

Over the years commentators have suggested all sorts of possible reasons for this divergence, from cultural proclivities to climactic differences.

Joe Studwell has a different explanation. In his new book, , the founding editor of argues that in the 1980s and 1990s governments in Southeast Asia made the mistake of accepting the policy recommendations of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

In response to advice from Washington, they distanced themselves from business, opened up their domestic markets and scrapped controls on capital flows.

In contrast, governments in northeast Asia adopted a much more interventionist, and protectionist, approach. In Japan, Korea and Taiwan post-war governments rode roughshod over property rights, redistributing farmland in order to maximise output from their underemployed rural populations.

Meanwhile, governments maintained a tight grip over their financial systems, holding domestic savings captive and directing cheap capital into favoured manufacturing industries.

The result was Japan's rapid growth of the 1960s, achieved thanks largely to the state's allocation of resources into nascent manufacturing industries which benefited handsomely from a protected home market and generous export incentives.

Similarly, in South Korea, the government directed investment into heavy industry - steel, shipbuilding and carmaking - promoting their development with subsidies and shutting out competitors with tariff barriers. Imports were restricted to raw materials and capital goods necessary for boosting productivity, with controls only relaxed once Korean industry was able to hold its own against international competition.

The lesson was well learned in Beijing. Although China never fully pushed through land reform after the disaster of collectivisation, Beijing enthusiastically embraced the other main elements of the northeast Asian model. The government retained control of the financial system, allocating cheap capital to protected state industries and promising export sectors. Growth took off.

According to Studwell, it's a model governments in newly developing economies in Africa and elsewhere would do well to study.

Throw the Washington rule book out of the window. First, equally redistribute your agricultural land to encourage small-scale intensive farming and boost output.

Next, protect your home markets from foreign competition, while picking winners in likely export sectors.

Finally, keep control of your financial system so you can lavish cheap capital on your favoured manufacturers until they can compete with all comers.

It's hardly a liberal approach, but it's worked a treat for Asia north of the 20th parallel.