China keeping its edge despite grim talk

Figures for FDI inflows tell only part of the story about the mainland's performance, and the rubbery basis for these numbers does not help

Foreign investment into mainland slows

SCMP headline, June 19

This is actually old news. It has been going on for almost two years and foreign direct investment (FDI), which was the subject of our report, presents a clouded picture anyway as most of it is unlikely to be truly foreign.

Let's start with the overall picture. Capital flow on the balance of payments represents money flowing into a country less money flowing out and, in practice, incorporates errors and omissions.

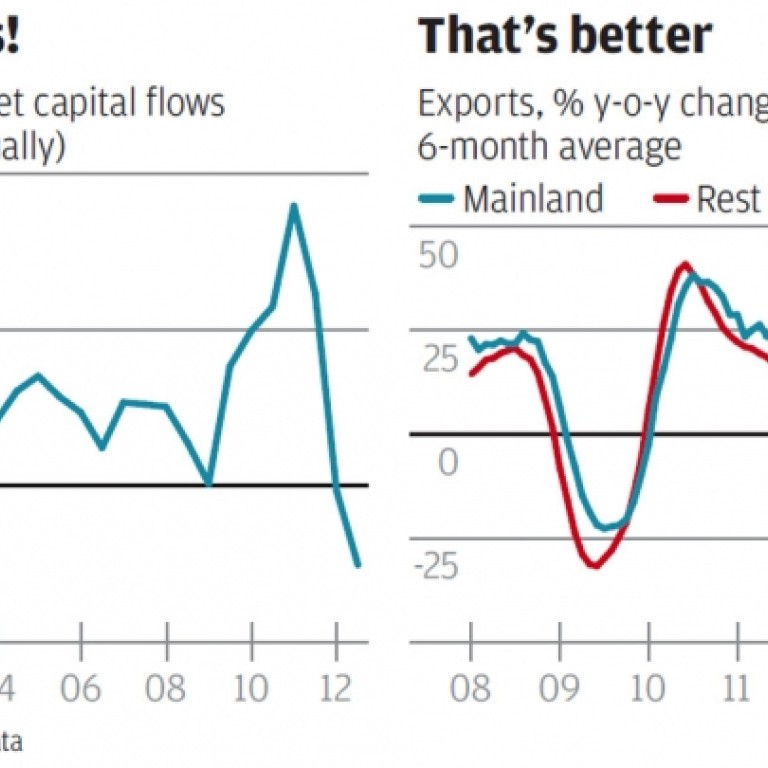

The first chart sets out where matters stand on this count on the mainland.

Two years ago saw a record net inflow of US$358 billion for the previous 12 months. Then the picture suddenly changed. As of the end of last year that inflow had changed to an annual net outflow of US$101 billion.

The culprit was not foreign direct investment. This held up fairly well throughout.

The collapse was in net flows of loans, currency movements and deposits, which in aggregate showed a net outflow of US$245 billion last year.

It is one of the reasons we hear more these days of troubles in the mainland banking system. It has certainly alarmed Beijing, which, in an effort to encourage confidence in the currency, has responded by pushing the foreign exchange value of the yuan to much stronger levels than had earlier been expected.

But there are two sides to the balance of payments - the current account and the capital account.

If the capital account has gone into deficit the overall balance can still be kept positive if the current account shows a greater surplus. This it has done.

I have only room for two charts in this column (boss's orders, although some day I hope to change his mind) and I have decided not to include the one on the current account as I have a better one to put things in perspective here.

The top blue line on the second chart represents the growth of the mainland's exports on a six-month average basis. The bottom red line sets out the equivalent performance for the rest of Asia. The two go up and down at the same time because export demand is dictated by the consumer, not the producer, but the mainland's export growth is positive and rising while the rest of Asia's is negative and falling.

In other words, for all the dire talk of an industrial slowdown, the figures say the mainland is still gaining export competitiveness.

The only difference is that it is now doing so in weak rather than strong export market conditions.

And as to the slowdown in direct investment, sometimes this money for industrial investment comes directly from export profits and sometimes these exports are sent out at a lower invoice value with a top-up margin added after they are outside the mainland's borders. In this second way the money can be treated as foreign investment when it comes back in, which gives it privileges not available to reinvested industrial earnings.

I don't know what the fine nuances of this game are at the moment but I do know that these numbers are never quite what they say they are.