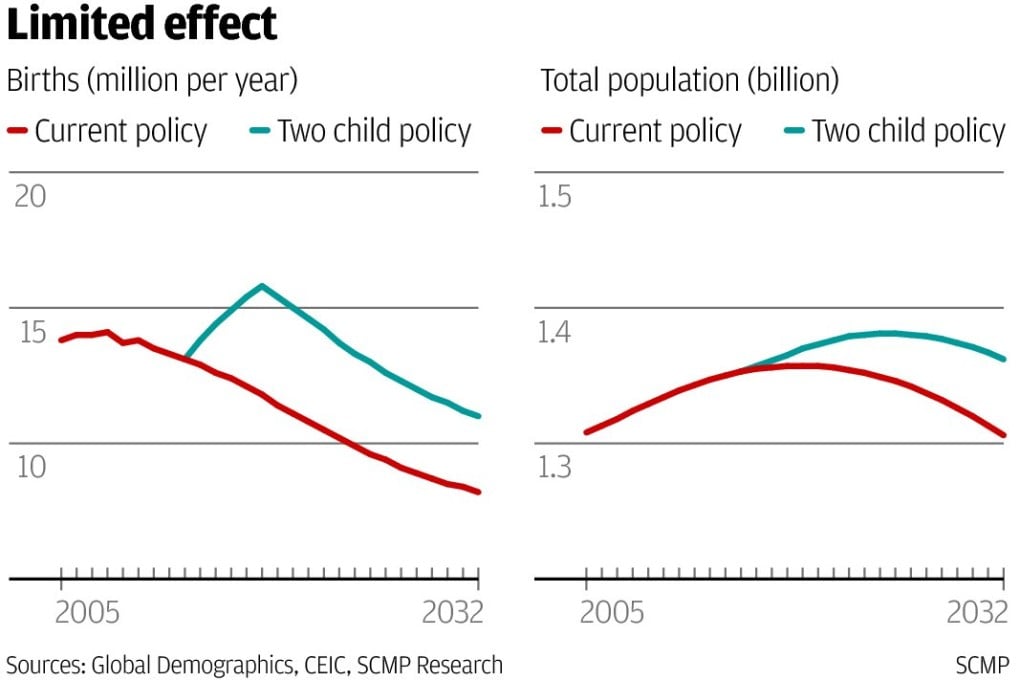

Monitor | Scrapping the one-child policy won't solve China's problems

While a loosening of the current repressive restriction of a basic human right should be welcomed, it will not prove to be an economic panacea

In the coming months, Beijing is set to relax its one-child policy.

On Monday, Xinhua reported that officials are "still deliberating" whether to allow more couples to have two babies.

But most observers expect the authorities to loosen the current rules next year, moving to a two-child policy a couple of years after.

Reaction to the news in international media and markets was uniformly upbeat.

London's Daily Telegraph said the loosening is needed "to avert an ageing crunch as the workforce goes into sharp decline", while The Wall Street Journal predicted "it will put the economy on a better footing for decades to come".