Selling down China's reserves could ease domestic problems

Emptying part of this US$3.66 trillion piggy bank would also help reduce the country’s overexposure to US Treasury debt

Last week China's leaders got an uncomfortable reminder of the risks they run by holding US$3.66 trillion in foreign exchange reserves.

As US politicians bickered over the administration's borrowing and spending plans, Chinese policymakers became increasingly nervous that the stand-off could force Washington to default on its Treasury bills and notes.

It could open its capital account, scrapping restrictions on the outflow of domestic savings

That, they feared, would blow a massive hole in the value of the US$1.3 trillion or so in US government debt owned by Beijing's reserve managers.

Although a default was averted, China's leaders would still like to have less of the US Treasury's debt. But unfortunately, when you are sitting on US$3.66 billion in assets, few markets are big or deep enough to offer you any meaningful diversification.

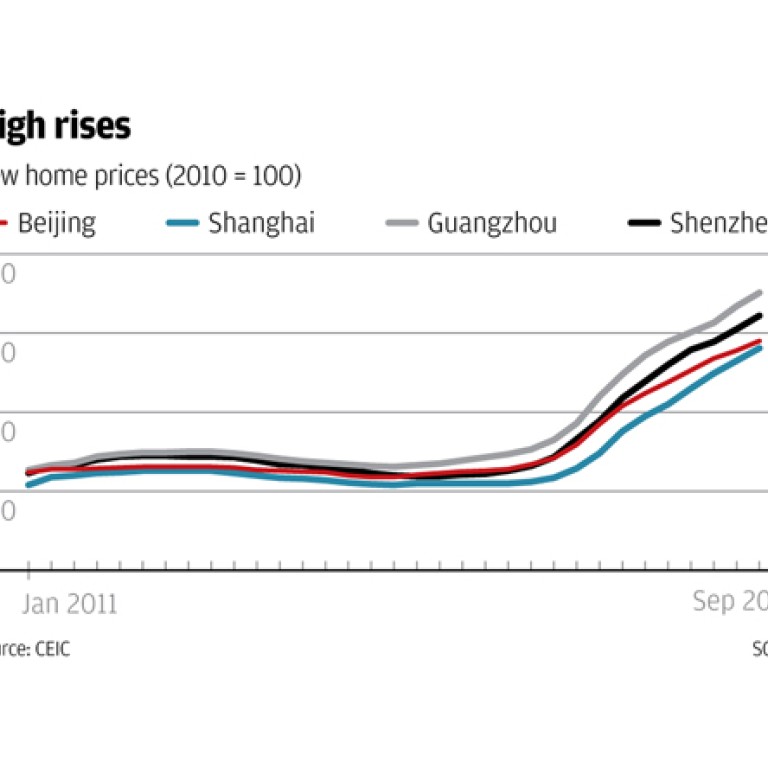

This week, Beijing's economic policymakers find themselves facing a different problem. Data released yesterday showed that nationwide home prices climbed 9 per cent over the year to September - the fastest increase in nearly three years.

In major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, the rate of increase was even faster. In Guangzhou and Shenzhen, prices shot up by almost 20 per cent, inflating fresh talk of a dangerous housing bubble.

In response to both the property market run-up and rising consumer inflation, there is talk that the central bank will be less generous with its money-market liquidity injections.

Whether that will be enough to contain inflationary pressure over the long run is doubtful.

But there is a way Beijing could tackle both problems - overexposure to US Treasury debt abroad, asset and consumer inflation at home - in one policy move: it could open its capital account, scrapping restrictions on the outflow of domestic savings.

Depending on the degree of simultaneous opening to inflows, a simple rebalancing of Chinese savings portfolios could lead to net capital outflows of between 4 trillion yuan and 10 trillion yuan, or between US$650 billion and US$1.6 trillion.

Under normal circumstances, such heavy outflows would put the yuan under enormous downward pressure. But the central bank could meet the demand for foreign currency and keep the yuan relatively stable by selling down a portion of its reserves.

That could help trim Beijing's exposure to US government debt, but it would also have a big effect on monetary conditions within China.

When the People's Bank of China built up its reserves, it financed its accumulation of foreign assets by running up domestic liabilities. In effect it printed money.

Much of that liquidity it mopped up by issuing short-term debt and by ordering banks to lodge more of their deposits with the central bank.

But this sterilisation process was imperfect. As a result, China's massive foreign reserve build-up was paralleled by a big expansion of domestic liquidity.

Running down the reserves would reverse the process. As the central bank sold foreign currency, it would buy back yuan, taking money out of circulation.

The reduction in liquidity would be partially offset by retiring central bank paper, but running down the foreign reserves would still result in a domestic monetary tightening. That would rein in consumer and property market inflation.

In short, scrapping capital controls could help solve two of China's most pressing financial problems. Accompanied by domestic interest rate liberalisation, the economic benefits would be enormous.

The political costs, however, would be heavy. Local governments and state-owned industries would find their access to plentiful cheap credit rudely curtailed. The result could be a state-sector debt crisis.

Unfortunately, that risk is probably enough to ensure Beijing looks for a gentler solution to its twin problems.