Does cheap money mean governments care about the future?

The appeal of cheap money is hard to shake, but as governments persist with low interest rates it is time they explain the longer-term benefits

We have been living in a low interest rate world since the Great Recession of 2008-2009. While the United States has pulled back slightly on quantitative easing, macroeconomic policy in various guises continues in the opposite direction in Japan, the euro zone, Britain and China. It is unlikely that cheap money will go away soon.

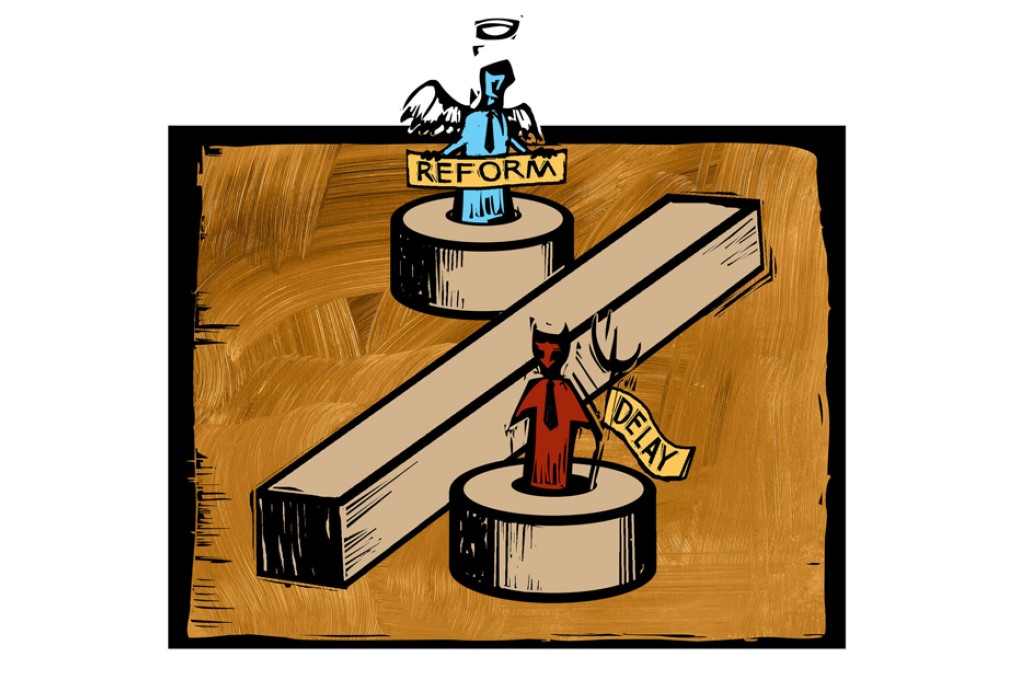

Opinion is divided on how sensible it is to rely on expansionist policies that facilitate cheap money, easy credit and low interest rates. Those doubting the wisdom of stimulus policies worry about asset bubbles, debt-fuelled growth and an accompanying reluctance to embrace the structural adjustments needed to spark improvements in productivity.

A strategy of postponement is more likely to serve the electoral cycle or regime survival

What the critics fear is an irreversible addiction to procrastination that will eventually lead to crisis. For a large number of countries, structural reforms to improve productivity are crucial to future prosperity.

The other side of the argument thinks in terms of Keynesian countercyclical action and the avoidance of needless austerity. It has worked before. Why would it not work again? Deflation can be as toxic as inflation.

These opposing views cannot be readily reconciled. The concerns are valid on both sides. Everything depends on time, place and the intensity with which a chosen stance is pursued. And, of course, considerable risks are attached to both stimulus and austerity.

But as my friend Richard Ward of HSBC and I were discussing recently, these arguments ignore a fundamental question that carries with it the makings of an interesting paradox. We commonly associate interest rates with time preference. The higher the interest rate, the greater the value assigned to the present in relation to the future. Low interest rates imply the reverse.

If the future were as highly valued as the present by our banks, they would extend us interest-free loans. They would be saying money has the same value in the future as it has today. That we can only dream of. Monetary institutions could, of course, still prosper the Islamic banking way, where interest is considered usury and equity partnership is the form that credit takes.