The View | Driverless cars: time for Hong Kong to step on the gas and grasp the future

Autonomous vehicle technology just needs a test bed, and we can provide it

It is not necessarily the fault of the Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission (ITC) that it is so difficult to live up to its grand title. It’s just that these government commissions – after all, a camel is a horse designed by a commission – never seem to amount to a hill of beans.

The ITC Commissioner is Annie Choi, a seasoned 30-year civil servant, who has served in such technological hot spots as the Civil Service Bureau and the Insurance Commission. It is not surprising that the ITC website is very domestic and boasts few links to the white heat of global innovation and technology as found in Silicon Valley, Silicon Fen, or any other silicate-related location.

The ITC, the billion-dollar Innovation and Technology Fund, the enterprise schemes to provide cash for ailing inventions; and the new HK$2 billion Innovation and Technology Venture Fund investing in local start-ups, are all laudable attempts to drive Hong Kong’s future. But how is a city of 7 million people, merely the 14th largest city in China, sitting on a pathetic 80 square kilometres of hillside, going to compete in technology with the big wide world?

Eventually driving will become a recreational sport like cycling – done between consenting persons in a private place

In our favour, we are rich and we have a lot of well-educated, globally minded people packed into a small space. We should find one good idea from overseas, pour our money into it, and make it a centre of excellence. Start with something that suits us perfectly and that is coming anyway – like driverless cars.

Elon Musk of Tesla believes that autonomous vehicles will be crossing the United States within two years. Ford chief executive Mark Fields reckons half a decade. Nissan’s boss, Carlos Ghosn, says, “I don’t see any impossible obstacle” to a five-year horizon. Anthony Foxx, US Secretary of Transportation, expects in 10 years to see them everywhere. This technology is not just coming – it is here. It just needs a test bed.

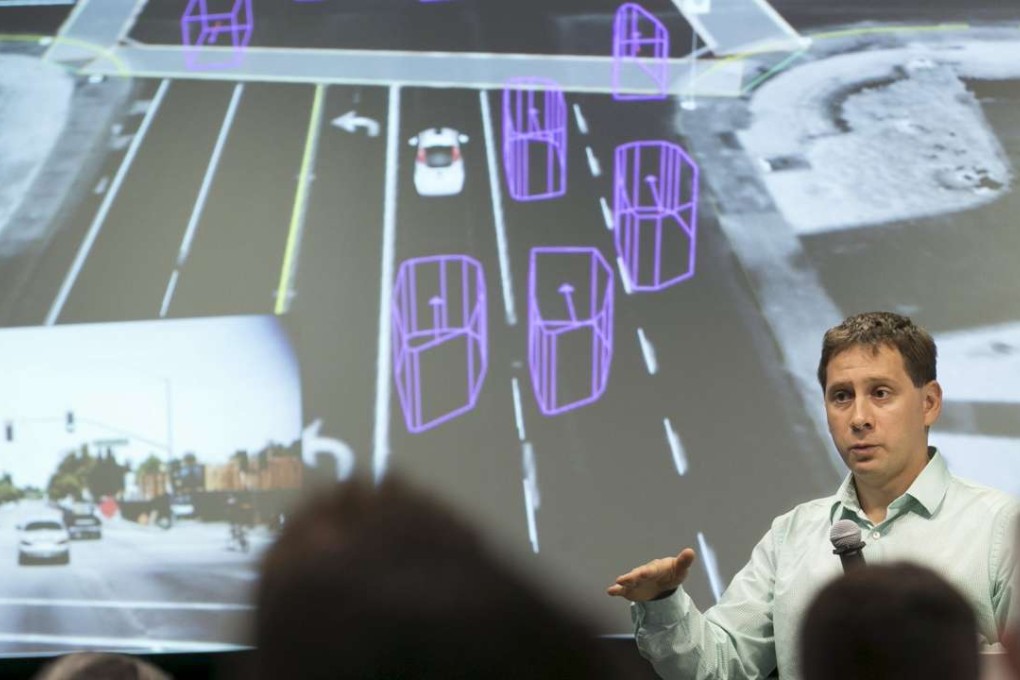

There is a flurry of development as we speak – Apple, Audi, BMW and Baidu, Fiat, Ford, GM, Google and Toyota, Mercedes, Nissan and NASA, Tesla, VW and Chinese bus manufacturer Yutong are just a few of those working on autonomous vehicles. There are still technological problems. Gill Pratt, head of the Toyota Research Institute said, “Most of it is easy, but a little bit is very hard.”

In 20 years time most of us will have stopped driving and will be using the time to work or play on our futuristic smartphones. No more waiting for a bus that comes full. No arguments with taxi drivers about crossing the harbour. No more blocking of the roads in Central by chauffeurs waiting to pick Mistress up from the shops. You will always have a robocar to pick you up, increasing your productivity.