The stifling of Hong Kong’s once unstoppable aspirations

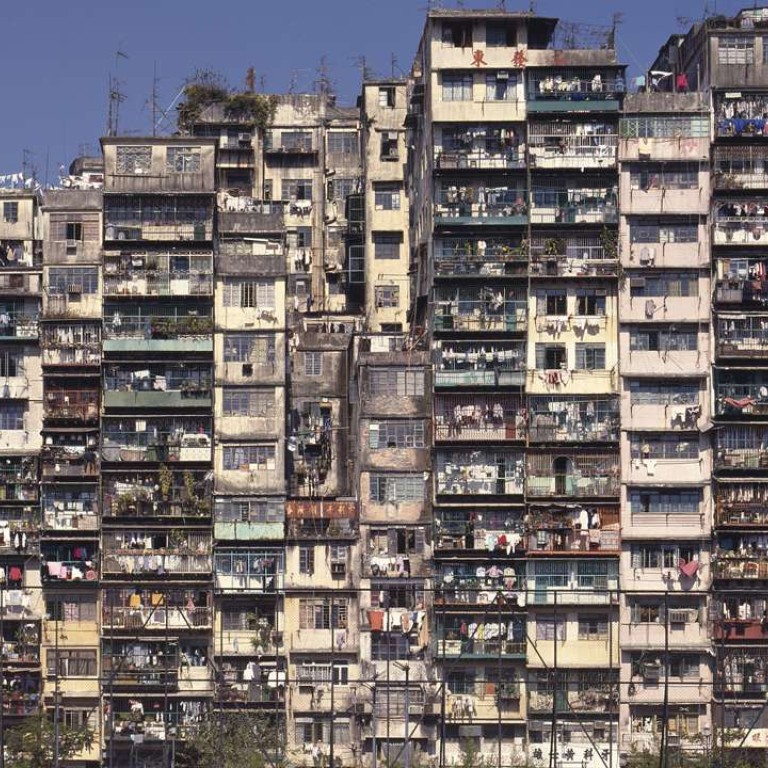

In the early 1980s as I sweated through the chaotic corrugated iron squatter shanties up above Sham Shui Po, or pawed through the dark, damp grotto we called Kowloon City, I would always marvel at two things: first, how could families living in such primitive circumstances walk out every morning with their children in crisp ironed shirts and shorts? And second, why were these communities not railing against the excesses of the local rich, and clamouring for a more even distribution of wealth, unemployment benefits, and minimum wages?

Local friends always explained that Hong Kong was an aspirational society. We may have arrived poor, but with hard work, we can become rich. If we invest in our children’s education, we and our families will be rewarded in due course. These were the days when Li Ka-shing was “superman”, and his rags to riches story front of mind for thousands of Hong Kong’s immigrant poor.

Today, those squatter shanties – and the Kowloon Walled City – are long gone, but why is the mood today so changed for the worse? Why the glowering political standoffs? Why the Occupy movement? Why the clamour for standard working hours and a minimum wage? Even more serious, why has business become a dirty word, seemingly synonymous with corruption, and perceptions of collusive back-room deals with government officials?

The first and most obvious answer is that Hong Kong has gone through a terrible couple of decades – and despite the predispositions of international journalists and some local politicos, this cannot be blamed on the 1997 change of sovereignty. From the Asian Financial Crisis through the dotcom crash and on to the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003 and the 2008 global crash, Hong Kong has seen nearly two decades of wage deflation while property prices have roared off over the horizon.

Since 2008, other economies worldwide have begun to feel similar angst-creating adversity, and the grim consequences of this are already clear in Trump, in Brexit, in Marine Le Pen, and so on.

Set against the extraordinary boom of the ’90s, with property still affordable for Hong Kong’s aspiring middle class, and full employment taken for granted, the two-decade reversal has been painful and demoralising. Since 1997, a significant proportion of the working population have lost jobs – perhaps several times – and had to re-enter the workforce on lower wages. Salary levels have for most stagnated, with little prospect of a change for the better any time soon.

The challenge is not that people are poor, even though Hong Kong has always been home to a significant number of poor people. Nor is it that the gap between Hong Kong’s rich and poor is wider than it has ever been – and wider than in most economies in the world. No, the challenge is that the chasm between Hong Kong’s poor and rich feels unbreachable. It no longer seems possible that we can start dirt poor like Li, and a generation later feel affluence as a reward for our steady and uncomplaining labour.

It is a paradox that this loss of confidence in Hong Kong’s ability to transform rags to riches is in part due to a sound education system that is largely meritocratic. As the children of poor immigrant parents reaped the benefits of a good education, so they easily surpassed the earnings of their parents. A sense of upward mobility was palpable. If poor kids were bright enough, they were able to earn degrees, and join the professional classes that brought wealth and respectability.

Today, this sense of upward mobility has faded. As the brighter kids have earned their degrees, so those without degrees feel a dense and impenetrable ceiling pressing down on them. That sense of aspiration has been squeezed out of us.

Instead of thinking about supporting specific businesses, [our leaders] should instead be thinking about development of a more business-friendly environment

This is all the heavier as Hong Kong has transformed from an entrepreneurial society to a largely managerial one. In the entrepreneurial heyday of Li’s youth, a combination of a few dollars, a good idea, a willingness to work hard, and perhaps a smattering of “streetwiseness” could quickly be translated into wealth and material comfort.

In the managerial society of today, wealth and prestige sit with professionals – accountants, lawyers, doctors, engineers. Paradoxically, entrepreneurship has not been lost – but in large part it has migrated. It sits with energetic mainland business executives who in Hong Kong can celebrate escape from the stifling hand of mainland bureaucracy, and it sits with international entrepreneurs raring to win access to an increasingly prosperous mainland middle class.

Hong Kong’s own young entrepreneurs have found it harder to launch their new small businesses, in particular as strangling rental costs create entry barriers that only large, influential and well-resourced companies can surmount. Government has given lip service to innovation, incubation and entrepreneurship, but substance has been lacking. Business organisations in Hong Kong have done themselves no favours by allowing themselves to become associated with Hong Kong’s tiny business elite, rather than with the imperative to fight for Hong Kong’s “business-friendliness” – the need for the economy to remain a hassle-free place in which to set up and operate a business, no matter big or small.

Against this backdrop, it is perhaps not surprising that government claims of support for innovation and bright young start-ups ring hollow. For many of our younger population, the sense of optimism, self-reliance and aspiration that simmered across the community in the ’70s and ’80s has irreversibly faded.

As CY Leung has laid out his final policy address, and as potential successors manoeuvre for electoral support for the upcoming Chief Executive election, it is surely timely for our leaders to think hard on this collapse of aspiration. Instead of thinking about supporting specific businesses, they should instead be thinking about development of a more business-friendly environment. Instead of being digital laggards, they should be ensuring that Hong Kong leads the world in building a digital infrastructure second to none.

And as we reach the end of the second decade of our five-decade transition from British colonial control, they should be thinking about enhanced connectivity with the Pearl River Delta – one of the world’s largest and strongest economic regions with a ferociously entrepreneurial business population. They should be exploring how to exploit Hong Kong’s unsurpassed abilities to link China’s economy to economies around the world to help those thousands of still-stifled mainland entrepreneurs to achieve their full potential. There is less difference between these and our own entrepreneurs than we imagine. Surely, there is aspiration left in us still.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view