China’s shadow banking woes force regulators to change course on policy making

The sobering fact that China’s shadow banking system now contributes about one-third the country’s total credit to the real economy is a stark lesson in how well-intentioned policy can lead to a financial mess.

Mainland financial authorities have been tightening rules to better police shadow credit since the beginning of this year, part of their plan to deleverage an economy facing lofty debt levels and high risk exposure.

The new policy direction conveys a message that shadow banking increasingly appears to be the bogeyman behind the world’s second-largest economy that’s trying to make the massive transition to a slower but more sustainable growth pattern.

But in hindsight, the root cause of the explosion in shadow banking was the central government’s attempts to spur economic growth and to reform a rigid banking sector.

The spread of shadow banking in China was the result of regulatory arbitrage under which business organisations capitalise on loopholes to circumvent unfavourable regulations.

“Regulatory arbitrage is not necessarily a negative term, which suggests that a company is embarking on dishonest practices to make money,” said Qian Jun, a professor of finance at Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance. “Instead, it’s a neutral term and the practices can be widely used in global financial markets.”

China’s sizeable shadow banking system, with assets estimated to be worth more than 100 trillion yuan (US$14.7 trillion), largely helped boost the business sector’s leverage ratio while sometimes putting depositor money at risk given the absence of an efficient regulatory mechanism.

Excluding lending between financial institutions, shadow credit is equivalent to about 90 per cent of China’s gross domestic product, or more than 60 trillion yuan, flowing into the country’s real economy, according to Wang Tao, head of China economic research with UBS Securities.

Total credit flowing into the real economy through the shadow banking system represents about one third of the country’s total loans to businesses and individuals.

State financial regulators including the central bank, the banking watchdog, securities and insurance regulators are now combining their efforts to stem the wild growth of the shadow banking sector, fuelled by worries of rising defaults which could cripple the already slowing economy.

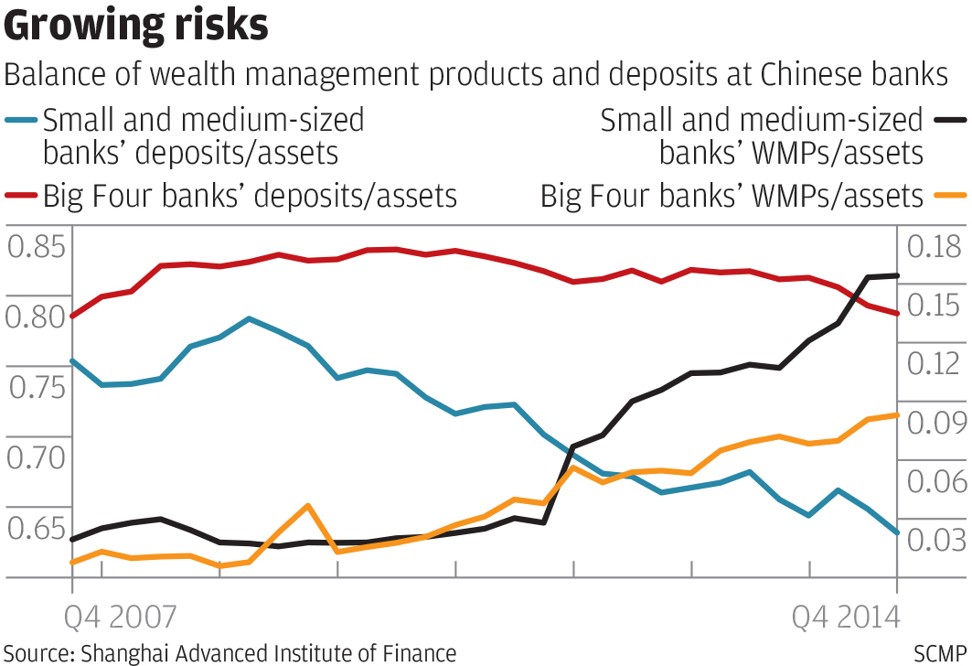

Wealth management products (WMPs), off-balance-sheet assets sold by mainland lenders to expand funding, are a typical example of how shadow banking has expanded.

Regulators recently stepped up risk assessment, including of WMPs, in their so-called macro prudential assessment framework that is being carried out in tandem with proposals for unified regulation to enhance monitoring efficiency.

“Enhanced regulatory policy measures and guidelines should further constrain the growth of off-balance-sheet WMPs, which have been one of the fastest-growing components of the shadow banking sector,” Moody’s Investors Service said in a report last week. “This is credit positive as it would gradually dampen banks’ incentive to engage in regulatory arbitrage, and reduce the risks in the shadow banking sector.”

It was the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package...that stimulated the sizzling growth of the shadow banking system

Indeed, the rapid growth of shadow credit, at an average of 60 to 70 per cent annually between 2011 and 2016, originated from the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package launched by Beijing to combat the global slowdown in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

The infrastructure-focused stimulus policies encouraged banks to grant easy credit to large-scale state-owned businesses to push forward with construction of mega projects.

At that time, the mainland’s mid- and small-size lenders, unable to meet their loan-to-deposit ratio amid soaring loans, resorted to WMPs to raise more funds to support their accelerated extension of credit lines, said Qian.

“It was the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package, an external factor, that stimulated the sizzling growth of the shadow banking system,” he said. “Regulators should be flexible in policy-making to engineer a long-term healthy growth of the financial sector. It is short sighted to implement reckless policies that would turn out to be detrimental.”

WMPs have been in existence on the mainland since 2003, with the central bank pinning hopes on such products to help liberalise the country’s interest-rate mechanism.

In order to attract more deposits, a WMP issued by a bank normally offers an interest rate higher than that suggested by the central bank.

Banks could also sell WMPs to clients on behalf of borrowers, charging only a service fee as a matchmaker, rather than as a banking institution.

Qian added that factors such as regulation, banks’ pursuit of growth, and investors chasing higher returns collectively influenced the growth of the shadow banking sector which in turn complicated the nature of the banking system.

“It is difficult for regulators to solve all the historical legacy problems without damaging a market-based system,” he said. “Besides, when drawing up regulations, regulators must take into account the business situations facing different levels of banks. One size does not fit all.”