Worrying economic parallels between China and India

China and India are very different countries with very different economies. But visiting his opposite number in New Delhi this week, Chinese premier Li Keqiang may well have been struck by some disquieting parallels.

China and India are very different countries with very different economies.

But visiting his opposite number in New Delhi this week, Chinese premier Li Keqiang may well have been struck by some disquieting parallels.

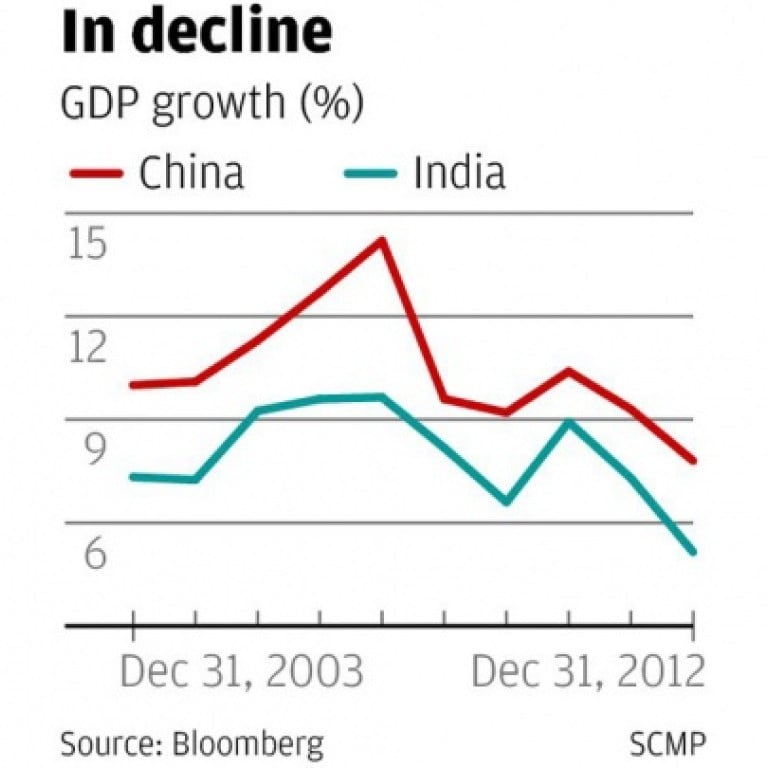

After years of rapid expansion, each country is now seeing a steep decline in its rate of economic growth.

What's more, to set their economic development on a sustainable trajectory for the future, leaders in both Beijing and New Delhi must push through far-reaching structural reforms in the face of stiff opposition from well-entrenched interests within their own domestic power structures.

In India, as in China, the danger is that too much government involvement in the economy may stifle future progress.

For much of the last 10 years, India enjoyed near double-digit growth rates in its gross domestic product.

But that growth was driven largely by high government spending, funded by swollen deficits at both the central and local government levels. In 2011, for example, the combined national and state government deficit reached almost 10 per cent of GDP.

Such lavish spending may have helped redistribute wealth and support growth, but it also exacerbated inflation and crowded out productive private sector investment.

As a result, both consumer and wholesale inflation rose to more than 10 per cent, forcing the central bank to raise interest rates to punitive levels. In response, private sector investment dropped from 27 per cent of GDP to 24 per cent.

Meanwhile, thanks to India's reliance on oil imports and Indian consumers' love affair with imported gold, the trade deficit surged, further weighing on economic growth, which slumped from 9 per cent in 2010 to just over 5 per cent last year.

In recent months, the central bank has done a good job of bringing down inflation and interest rates. But to secure India's future growth prospects, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh needs to press ahead with an ambitious agenda of structural reforms to reduce official budget deficits, deregulate the economy and encourage private investment.

The government has made a start, cutting fuel and fertiliser subsidies, streamlining welfare payments and planning a nationwide value-added tax.

The cabinet has also pledged to speed up the approval process for infrastructure projects and has introduced financial sector reforms.

But efforts to tackle India's chronic power shortages appear to have stalled, and so far there has been little progress towards rewriting restrictive land-use and labour laws.

Worse, there are fears of another public spending binge ahead of elections due by the middle of next year, which could further undermine the government's fiscal position. Unimpressed by talk of fiscal consolidation, ratings agency Standard & Poor's warned last week that there is a one in three chance it could downgrade India's sovereign debt rating to junk status.

China, too, is slowing from double-digit growth rates. But Beijing's trouble is not too little investment, but too much, raising the threat of over-capacity, declining returns on assets and a possible debt crisis.

To switch the economy towards a more sustainable, more consumption-driven, growth path, Li has outlined a bold programme of reforms.

These include interest rate liberalisation, which should help direct capital to more productive investments, and reform of the household registration system, land rights and social welfare system, all of which should encourage consumer demand.

But so far the reform programme remains just an outline. Timetables are fuzzy, and opposition from the state sector and powerful industrial lobbies, which benefit from cheap capital, low-cost migrant workers and favourable access to land, is certain to be strong.

Yet despite the political obstacles, it is essential that the leaders of both China and India persevere with structural reform.

Unless they each move to a more deregulated model in which the government plays a smaller role in the economy - that of regulator rather than dominant participant - the danger is that growth rates in both countries will continue to dwindle.

That would mean Asia's two emerging economic superpowers fall into the dreaded middle-income trap of stalled development.

Let's hope the leaders exchanged a few useful tips this week in New Delhi.