China’s one belt, one road plan covers more than half of the population, 75 per cent of energy resources and 40 per cent of world’s GDP

It has been estimated that this emerging network could be pumping out upwards of US$2.5 trillion of annual trade value by 2025

With six major economic corridors extending over Eurasia, China’s one belt, one road initiative stands to reshape the region’s infrastructure network, improve connectivity across the continent, and fill in some of the underdeveloped gaps along the way.

Spanning over 60 countries, this massive project will spread an interconnected network of rail lines, highways, pipelines and logistics zones from China to Europe, covering a potential market that includes more than half of the population, 75 per cent of the known energy resources, and 40 per cent of gross domestic product in the world.

It has been estimated that this emerging network could be pumping out upwards of US$2.5 trillion of annual trade value by 2025.

“The potential result of [the initiative] is an intensification of trade flows across the whole of Eurasia to a level of significance that has not been seen since the decline of the original Silk Road more than 500 years ago,” says Frans-Paul van der Putten of the Clingendael Institute, a Dutch policy research organisation.

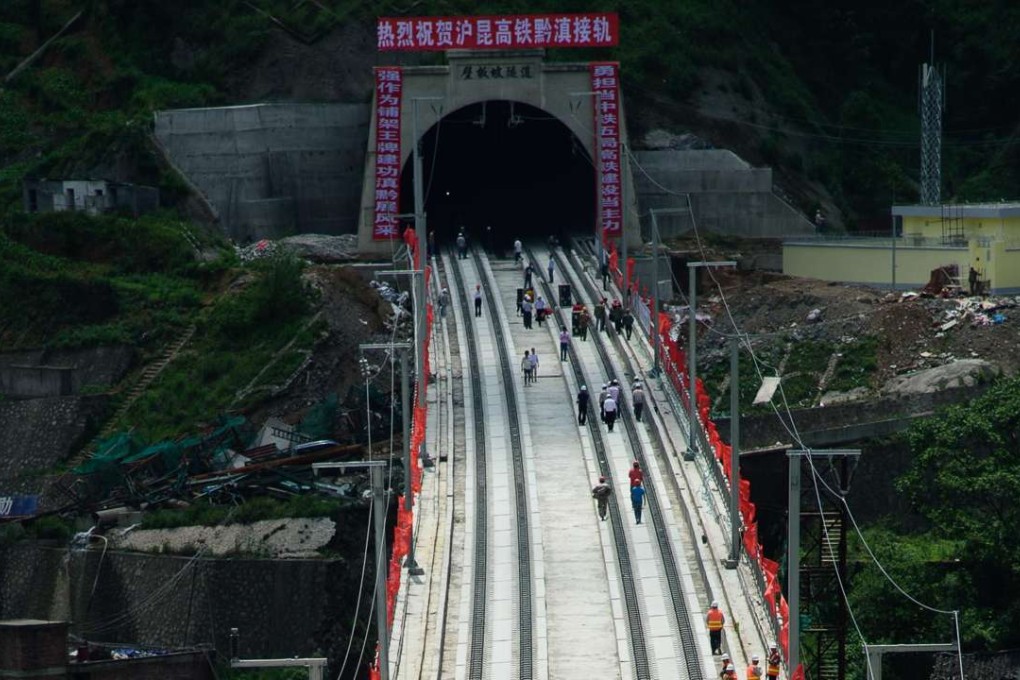

Some of the new infrastructure projects arising along some of the initiative’s economic corridors include new urbanisation projects in the far western regions of China, the massive Khorgos Gateway logistics and special economic zone on the border of China and Kazakhstan, a deep sea port and new port city in Sri Lanka, the Gwadar deep sea port in Pakistan, large-scale hydro, wind and coal power plants in multiple countries, and thousands of kilometres of new rail links and highways extending from East Asia to Western Europe.

In January, the US$100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was open for business. Initially a Chinese concept to create a financial institution to provide funding for the building of infrastructure across Asia, which could complement the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and World Bank, the new fund has grown to include 37 states.