How MacLehose shifted priorities from resettling squatters to accommodating low-income households

While the housing policy mistakes of the past cannot explain all the causes of the 1967 Riots, they did have a role to play

After the 1967 Riots and with the arrival of Governor Murray MacLehose, more policies in support of the disadvantaged were adopted in Hong Kong.

The great expansion of public housing was the centrepiece of MacLehose’s new policy initiatives. But this also presented considerable challenges for government in terms of land acquisition and finding the required resources.

MacLehose correctly recognised that while the 1967 Riots were triggered by an industrial dispute, the public’s strongest complaints about life in Hong Kong centred on the harsh housing conditions that most residents had to endure.

Their sense of injustice was exacerbated by the allocation of many valuable public housing units to squatters rather than low-income households. Many of these squatters had incomes above the median level.

This situation had been created by a series of bad decisions that I outlined in my column last week – rent control in 1947, the resettlement of squatters in 1954, and a poorly executed amendment of the plot ratio in 1962.

MacLehose’s programme announced a shift in priorities from resettling squatters to accommodating low-income households.

The early years of the resettlement rental housing policy nonetheless continued to determine the shape of housing policy. A large proportion of households ended up renting not owning their homes – at its peak in 1976, some 42.2 per cent of all households were accommodated in public rental housing units.

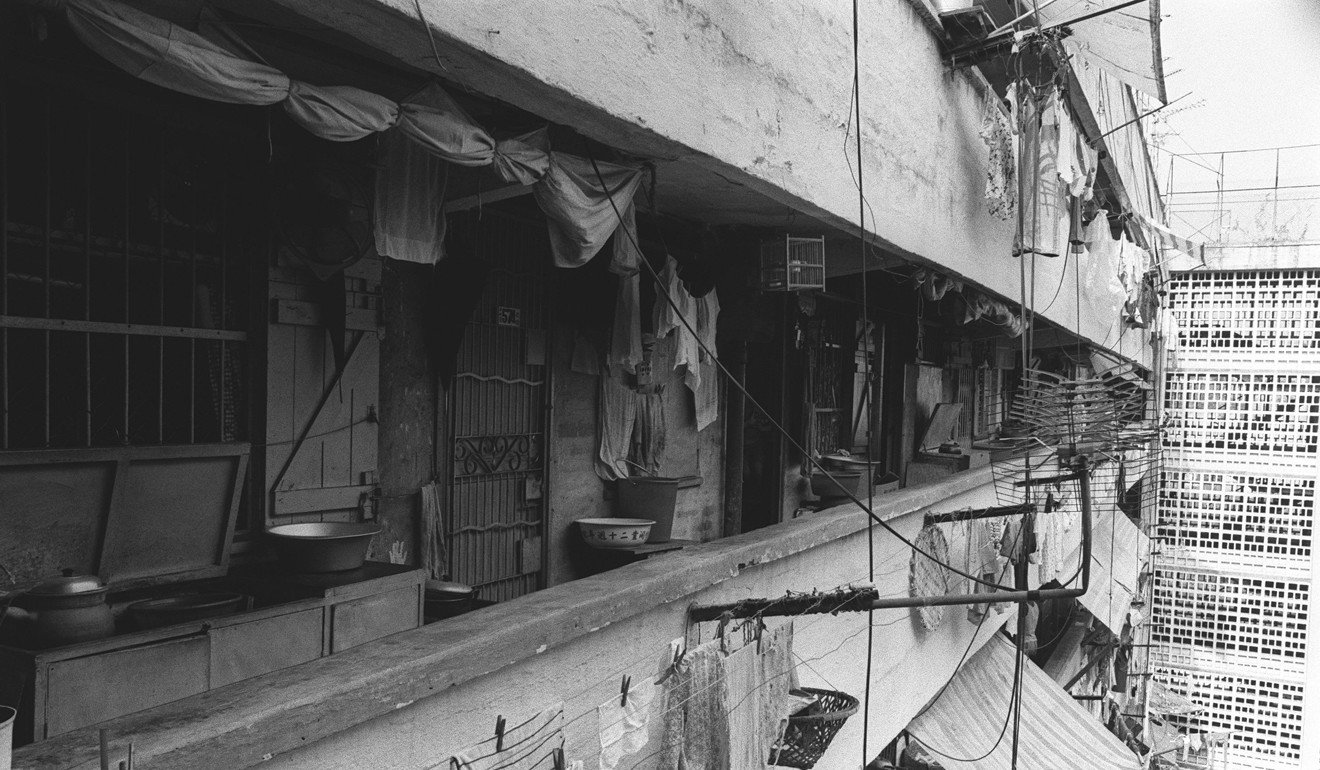

These units were (and still are) very small, a legacy of the resettlement programme. Urban land was in short supply, so resettled squatters were provided with an extremely basic standard. This decision exerted a lasting influence on the size of all future public housing units and even those in the private sector.

MacLehose’s Ten-Year Plan required vast amounts of land, which had implications for land policy in the New Territories where such land was available. Most of it consisted of small agricultural plots owned by indigenous residents and the task of assembling land for development was quite formidable in terms of both time and cost.

Therefore, new market exchange institutional arrangements in the forms of “Letters B” and the “small house policy” were created to facilitate the surrender and assembly of land through exchange.

These arrangements were an ingenious answer to the dual problem of finding land and funding construction with minimal coercion.

They overcame the propensity to withhold land and resist development, and made it possible to assemble many small dispersed plots of land into larger contiguous pieces that could be usefully deployed with greater efficiency.

The lingering presence of non-means tested squatters in public housing, however, contributed to the “well off tenants” problem and concern about preventing public rental housing tenancies from being inherited by the next generation.

Formal measures were introduced in 1984 to force “well off tenants” that failed the means test to either surrender their units or pay “double rent”.

Although this failed to drive out the original tenants, it got their children to exit to avoid breaching the household income threshold.

Some of these children, however, did not have high incomes and had to rent in the private housing sector. The irony is that it has helped to drive up rents there in the past decade and led to the mushrooming of sub-divided private housing units, now estimated to be 200,000 units. It has also exposed the odd situation that public housing cannot be sub-divided, but private housing can.

Finally there is the Homeownership Scheme (HOS), introduced in 1978. This was meant to provide a housing ladder for households whose economic conditions improved over time.

The units were sold at a discount to market rates. However, soon after being introduced, a requirement was added that the unpaid land premium be repaid, to be determined at present-day values.

Owners cannot resell until they repay, meaning they do not have 100 per cent ownership. As property prices have risen, most owners have become stuck in their unit without the prospect of upgrading into the private sector. Higher property prices mean more rungs on the housing ladder vanish. The ladder ceases to function.

The rent control in 1947 and squatter resettlement in 1954 set Hong Kong’s public housing policy on the trajectory of public rental housing and a pseudo-subsidised home ownership that deprived some half the population from sharing in Hong Kong’s rising prosperity. This is most unfortunate.

While the housing policy mistakes of our past cannot explain all the causes of the 1967 Riots, they did have a role to play.

Would the visionary Governor MacLehose have imagined an ambitious housing plan not anchored in public rental housing if the resettlement programme had not been entrenched? It is hard to say. But must we forever be trapped in the past? The market-like institutions introduced to find land and fund the building programme suggest that creative deviations from the standard fare are always possible for those who are bold and thoughtful.

Richard Wong is the Philip Wong Kennedy Wong Professor in Political Economy at the University of Hong Kong