Rethinking Hong Kong’s future housing policy commitment – rental or ownership?

Hong Kong’s experience is particularly valuable because it has both a private housing market and a non-market public housing sector that adjust to excess demand in different and opposite ways

Everyone in Hong Kong knows that there is a huge shortage of housing in the city. The government has been working very hard to increase supply and manage (or suppress) demand. But the effort has not yielded much success so far.

Property prices and rents in the private sector have continued to soar, while the waiting list to get into public housing gets ever longer.

The past decade has been a fascinating opportunity for students of economics to observe how a housing market adjusts to extreme shortage.

Hong Kong’s experience is particularly valuable because it has both a private housing market and a non-market public housing sector that adjust to excess demand in different and opposite ways.

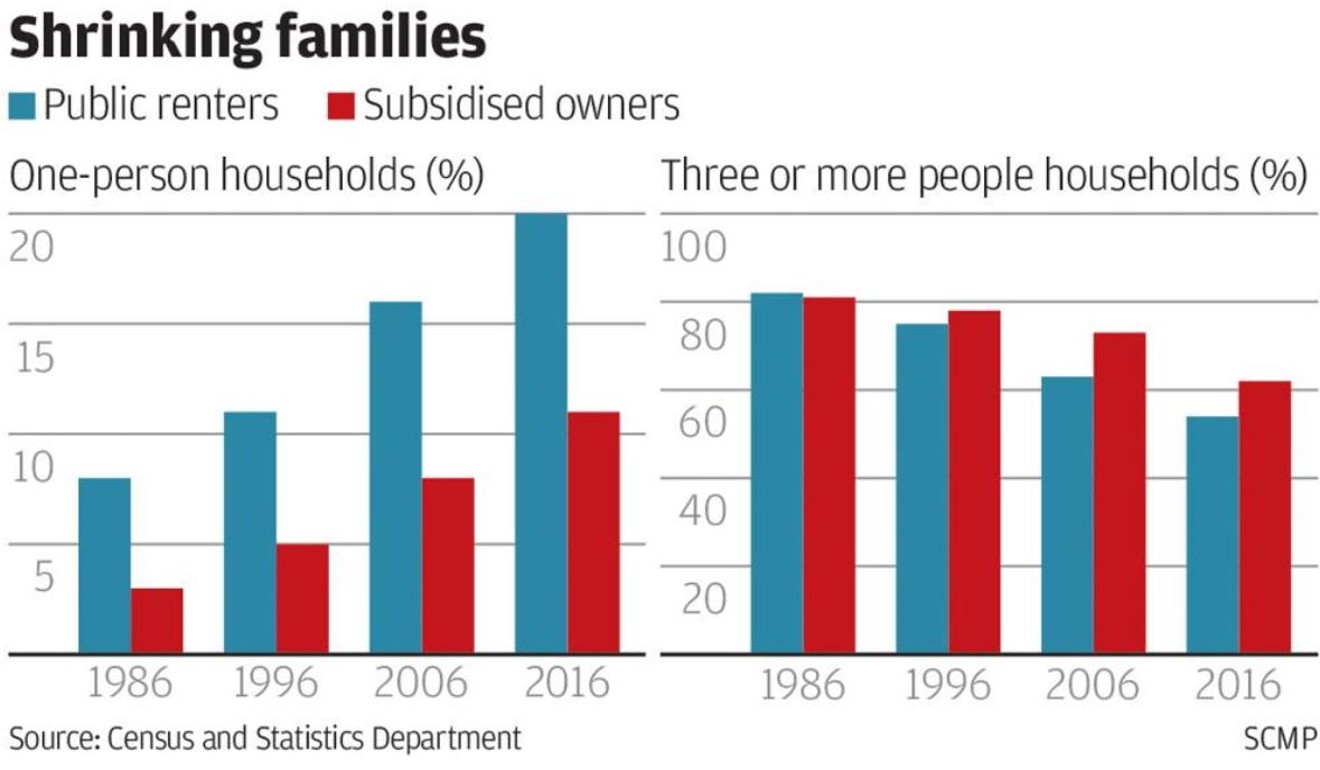

Interestingly, among private sector homeowners and renters, the average household size decreased by about 3.5 per cent and increased by 2.5 per cent, respectively, from 2006-2016, while that of subsidised homeowners and tenants decreased by about 8.5 and 3.5 per cent.

Many private sector homeowners and tenants responded to the rapidly rising shortage of housing by using their residential space more intensely to economise on high property prices and rents.

By contrast, many public sector homeowners and tenants downsized their household size, which implied using their residential space less intensively.

Public tenants have few incentives to economise on residential space since their rents are controlled and subsidised.

The past decade has been a fascinating opportunity for students of economics to observe how a housing market adjusts to extreme shortage

In addition, some well-off tenants avoided paying double rent if their working adult children moved out. This not only increased the demand for private rental housing but also for public rental housing – undermining the intention of double rents to encourage efficient use of public housing resources. The waiting list for public rental housing naturally grew longer and longer.

The adult working children from subsidised home ownership units who moved out of their parents’ premises into the private rental-housing sector have similarly helped to lengthen the waiting list for public rental housing.

When new Homeownership units are available for sale, some also take part in the lottery to try their luck.

Occupants in the public and private housing sectors face different incentives.

Part of the reason is the heavier concentration of elderly households in the public rental-housing sector, the result of a rule that favours the elderly. But even among households aged 40-59, there was still a rising share of one-person households.

Another reason why there are more small-sized households among public renters is the higher divorce rate. Looking at 20-59 year old households in 2016, 41.6 per cent of divorced individuals lived in the public rental-housing sector even though the percentage share of public rental households was only 25.4 per cent.

By contrast, 12.2 per cent of divorced individuals lived in subsidised ownership housing where the percentage share of subsidised households was 14.8 per cent.

Public housing renters who divorce face no housing allocation disincentive, as their eligibility for public rental housing is unaffected. But subsidised homeowners face the prospect of having to share or lose the subsidised housing asset in the divorce settlement.

The private housing market has been more efficient in adapting to rising housing shortages by accommodating more people in limited residential space compared with the public housing sector.

And within the public housing sector, subsidised ownership housing has accommodated the shortage more effectively than public rental housing.

Is it surprising that once again the presence of markets and property ownership have triumphed over the non-market public housing sector in adjusting to housing shortages?

It is certainly time to rethink the future of our public housing policy commitment – rental versus ownership.