Overcapacity plagues aluminium sector

Despite losses, smelters are ignoring Beijing's orders to shut inefficient plants amid pressure from local governments

Since 2003, Beijing has issued at least three policy circulars ordering the aluminium industry to correct its overcapacity problem, caused by local governments' pursuit of their own interests.

Until the central government finds an effective way to motivate local officials to change their penchant for investment-led economic growth and to launch a crackdown that bites, analysts say, overcapacity will not be resolved despite strong growth in domestic demand for the lightweight and versatile metal.

"It is a big challenge for the authorities to untangle the power of [vested interests] and to take back some sort of control or reform those industries," said Mark Pervan, the head of commodity research at ANZ Investment Bank. "The local governments don't appear to get the message that you need to shut some inefficient capacity."

Overcapacity has plagued not only the aluminium sector but also copper and steel smelting. All three grind on with low profits or losses as falling product prices, rising energy and environmental protection compliance costs and falling supply of domestic raw materials erode earnings.

The situation prompted the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology to issue on July 25 an edict for 1,433 firms in 19 energy-intensive and polluting industries to shut down and dismantle outdated and inefficient plants by year-end.

The ministry said this was the first batch of firms and projects, without giving the eventual scale of the crackdown. Only nine steel firms were ordered to close down 2.8 million tonnes of annual capacity, a drop in the bucket compared with the steel sector's annualised output of 786 million tonnes in the first half.

The China Iron & Steel Association estimated the industry had 300 million tonnes of excess capacity last year.

Just four firms were asked to shutter plants with a combined 260,000 tonnes of annual capacity. Last year's national output was 23 million tonnes.

"The government has been issuing policy after policy for many years. People do not want to listen any more, they want action," said Helen Lau, an analyst at brokerage UOB Kay Hian. "We need to see whether industry capacity keeps rising, whether local governments and banks are still supporting new capacity."

A report by the steel association on July 29 painted a grim picture. Citing industry data provider Mysteel, it said 31 blast furnaces were under construction, with total annual capacity of 38 million tonnes.

"Although steel prices are falling, almost no steel mill has cut back on output, as they worry about losing market share and bank loans, and they face pressure from local governments to maintain economic growth," the association said. "Ever rising capacity propagated more depressed market conditions."

The aluminium industry is not faring any better.

Citing figures from the China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association, Xinhua's reported the mainland had 27 million tonnes of annual aluminium production capacity last year.

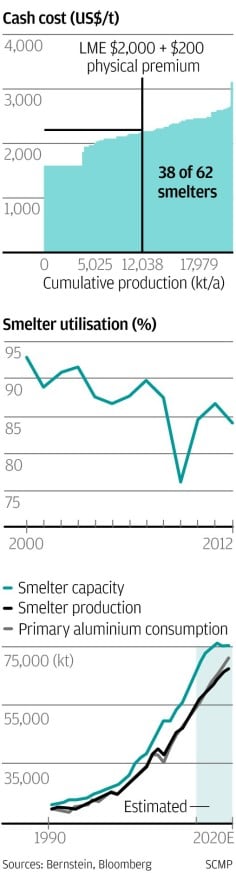

With output of 20 million tonnes, implied capacity utilisation was 74 per cent. Ninety-three per cent of the smelters made losses last year, it said.

While the dire situation should prompt the industry to reduce overcapacity, the association forecast that existing and new-build industry capacity could exceed 33 million tonnes by 2015 when projects under construction came on stream. If projects being planned were realised, the capacity could even surpass 40 million tonnes.

Fixed-asset investment in aluminium smelters rose 24.9 per cent last year, in contrast with a 5 per cent fall in other non-ferrous metals smelting.

Bocom International Securities analyst Benjamin Pei said this was due to investment in new smelters in western China, mainly in coal-rich Xinjiang autonomous region and hydro power-endowed Gansu province.

A Xinjiang smelter could have a cost advantage of 4,250 yuan (HK$5,380) per tonne with its own coal-fired power plant over an eastern China smelter buying power externally, said Vanessa Lau, a senior analyst at US brokerage Sanford Bernstein.

Power accounts for about 40 per cent of a smelter's operating costs.

The savings, calculated after taking into account the extra cost to transport raw materials and finished products over 3,000 kilometres each way by rail, amount to almost 40 per cent of the price of aluminium.

Lau said the economics meant Xinjiang's annual aluminium smelting capacity could rise to 8 million tonnes in 2018 from 1 million tonnes last year, based on the existing project pipeline. The pace of expansion will depend on railway capacity expansion.

Investing in more cost-competitive new plants is good for the industry, but getting rid of outdated, inefficient and pollution-prone old plants is difficult. Their existence limits the recovery of aluminium prices, as owners of these plants will resume their operation once prices rise to levels above their cash costs.

"While Premier Li Keqiang recently vowed to ban the supply of new credit for construction projects in industries with severe overcapacity, we can only wait and see the results," Pei said. "Previous policy initiatives have clearly been unsuccessful."

In a 2009 circular on the restructuring of the mainland's non-ferrous industries, the State Council said it would in principle not approve new aluminium smelting projects or expansion of existing ones for three years.

In 2003 and 2011, it also issued orders for local governments to put a stop to overbuilding.

Pei said the crux of the problem was that Beijing relied on local governments to carry out its policy on phasing out old plants in eastern and central China, but that involved giving up tax revenues and jobs.

Although smelting is not profitable, local governments collect value-added tax from the production of aluminium, as well as profit tax from power generators.

While industry officials have proposed subsidies to incentivise the shutting down of old plants, Pei said it would not be easy because of limited state resources.

State policy aside, Zhang Bo, the chairman of privately owned China Hongqiao, the country's third-largest aluminium smelter, said last week a bigger "second wave" in the overhauling of the industry would soon occur as new plants supported by cheap electricity from abroad would force barely surviving mainland plants to close.

The first wave involved capacity that was severely out of date, the second would hit plants that still survived but would face stiffer rivalry from imports, Zhang warned.

Despite low aluminium prices and widespread losses in the industry, Hongqiao is among the most profitable smelters on the mainland, thanks to its strategy of being highly self-reliant in electricity and supply of the raw material alumina.

With coal prices having fallen almost a third since late 2011, the company was in a much better position to weather falling aluminium prices than rivals that rely on grid-supplied power.

With the cash-market price trading at about US$1,860 a tonne, 34 per cent below the peak in 2011, Pei and Lau said further downside was limited as it was close to the industry's average cash production cost. Lau expects global supply to exceed demand until at least 2017.

State-backed Aluminum Corp of China (Chalco), the country's largest producer of the metal, announced in June a temporary cut of 380,000 tonnes of smelting capacity, or 9 per cent of last year's output. It also unveiled various transactions to dispose of loss-making operations to parent firm Chinalco to narrow its losses and lighten its debt load.

Chalco booked a net loss of 8.23 billion yuan last year, its second annual loss since 2009, when it lost 4.6 billion yuan, and a far cry from the record profit of 11.8 billion yuan in 2006. This is although its aluminium output has jumped 119 per cent since 2006.