Some disasters can defeat a firm's best efforts at crisis communications

The disappearance of Malaysia Airlines' jetliner has put to the test the firm's crisis communications experts, who can only hope to limit damage

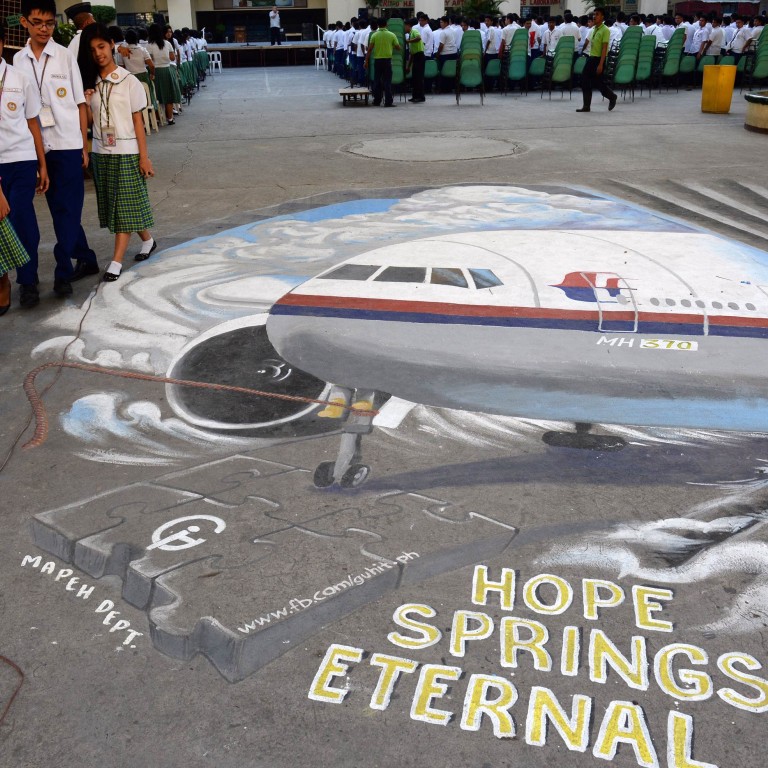

It is hard to think of a tougher or less comfortable job than being responsible for public relations at Malaysia Airlines as the search continues for the missing flight MH370, carrying 239 passengers and crew.

To pre-empt understandable misgivings about discussing this aspect of the MH370 disappearance when the fate of those onboard remains unknown, it should be stressed that concern over human life is the absolute priority, but corporate reputation is also important and can have an enormous impact on many people's lives for years to come.

As with so many unpalatable things, we can thank so-called experts for coming up with a title that obscures the reality of tackling profoundly saddening events. The title in this case is "crisis communications".

Once the problem has been identified, a clear-cut attempt to provide solutions is vital

But no amount of preparation will be adequate for handling a crisis on the scale of the disappearance of MH370.

A wonderfully named "Reputation Review Report" published by the advisory firm Oxford Matrica in 2012 found that there is an 80 per cent likelihood of a company losing at least 20 per cent of its value in the aftermath of a disastrous event and that this can continue over a five-year period. More disastrous events will trigger much bigger falls.

A case in point is the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, primarily affecting the British oil firm BP. The immediate impact was to slice BP's stock market valuation in half over a 50-day period. BP has clawed back much of this loss, but its share price is still about a third below pre-disaster levels.

It remains to be seen what will happen to the value of MAS shares, but there was an immediate loss of 18 per cent after the plane's disappearance.

Like BP, MAS has a good reputation to lose, but the airline is more vulnerable because there are few businesses quite so reliant on public confidence as an airline. No one in their right mind will choose to fly with a company perceived to be unsafe or uncaring about safety.

The worst way to provide reassurance is to get some smart alec to produce figures showing how good the firm is on average; in other words, trying to prove that the incident on everyone's mind is some kind of aberration.

The reality is that playing the averages game only serves to call attention to the very incident that they are trying to avoid mentioning and suggests that the company is not focusing on the priorities to hand but looking for ways to ignore them.

Yet it is quite surprising how often companies think they are being clever by mustering up statistics designed to put themselves in a better light.

I know something about this from experience in my business, where food safety is a crucial and time-consuming subject.

Practically every company in this business has faced instances of real or alleged food poisoning. There is no surer way of annoying the victims than by telling them how unlucky they are, because no one else has had food poisoning, while claiming that the overall food safety record is good.

Compensation, monetary or otherwise, provides some amelioration, but fundamentally what matters is the manner of the response. Companies need to demonstrate seriousness and determination to get to the bottom of the problem.

They also need to be honest and provide timely factual information. In the internet age, only stupid people believe that burying disturbing facts is a possible solution.

Once the problem has been identified, a clear-cut attempt to provide solutions is vital.

There is still no concrete information about what happened to MH370, but whatever occurred will require MAS to clearly set out ways in which it will enhance airline safety.

This alone will not be sufficient to restore confidence, because this disaster is simply too big and too public to not have a severely detrimental impact. However, even airlines can recover from disasters, man-made or otherwise.

Air France, for example, is still in business even though it took two years to adequately explain what happened to Flight 447, which disappeared on a Rio de Janeiro-Paris run in 2009.

MAS has been widely criticised for its response to the crisis, but some of this criticism has been unjust, especially when officials are castigated for not providing information that they simply do not have.

However, faced with the desperation of the relatives of passengers, fear of the unknown and a complex set of circumstances, MAS has little chance of coming out of this with its reputation intact; it is no exaggeration to say this could fatally damage the company. At best, there will be damage limitation, and people may come to understand that the airline did its utmost in difficult circumstances.

However, the limits of a so-called crisis communications strategy will be there for all to see. The blunt truth is that some things are well beyond corporate control.