Rise of Xiaomi: the Chinese start-up poised to become world’s biggest IPO of 2018

Stock exchange officials from New York, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore are trying to pitch their bourses on what would probably be the largest global initial public offering in four years

Lei Jun is a busy man. On a recent Saturday, his first full day in Xiaomi’s Beijing headquarters in three weeks, the founder of the world’s fourth-largest smartphone maker had scheduled 11 back-to-back meetings with board members, government officials, colleagues and customers.

A successful offer, expected in the summer, could make Lei China’s wealthiest man a few months before he turns 49 in December.

Xiaomi’s billionaire founder reveals his formula for success

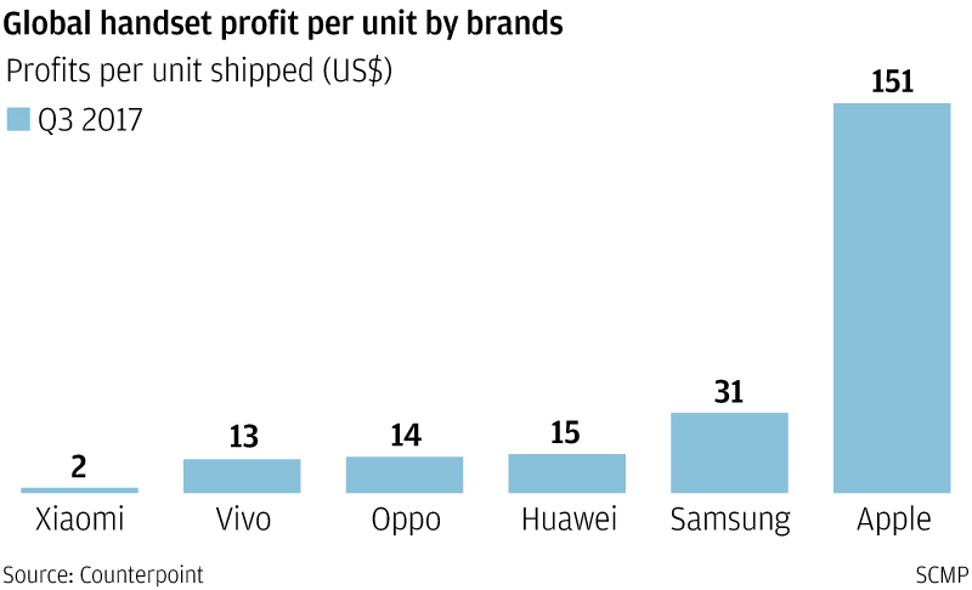

“I started Xiaomi after turning 40, and had figured out 90 per cent of the business model before starting the project,” Lei said. “We created this business model that we call “tipping”, which is to sell our hardware at zero or low profit margin, but monetise our complementary services.”

I call it the triathlete of the New Economy, where Xiaomi makes hardware and devices, sells its products through e-commerce and offers services on the internet

Xiaomi’s valuation has more than doubled from its most recent 2014 fundraising when it was valued at US$45 billion, according to a person familiar with the guidance in the company’s IPO plan, requesting anonymity to discuss a confidential matter.

With Lei’s stake in Xiaomi estimated at 77.8 per cent by the financial news site Yicai Global, that valuation would make him China’s wealthiest man, surpassing the US$45.3 billion fortune of Tencent’s founder Pony Ma Huateng, and the estimated US$39 billion wealth of Alibaba Group Holdings’ founder Jack Ma Yun.

“I call it the triathlete of the New Economy, where Xiaomi makes hardware and devices, sells its products through e-commerce and offers services on the internet,” Lei said.

He believes in a certain degree of decency in business. “We sell our smartphones at affordable prices, but if you use our browser, watch streaming video on our phones, or use our online services, we earn a profit,” he said.

How Chinese start-up Xiaomi became India’s top smartphone brand

“China has understood that providing value for money is very important in emerging markets,” said Narayana Murthy, founder of India’s second-biggest technology company Infosys, during an interview in Hong Kong. “Look at Xiaomi: I don’t find it any worse than any other brand, but it is so inexpensive and so much value for money. Why would I waste 10 times the price and buy anything else?”

Look at Xiaomi: I don’t find it any worse than any other brand, but it is so inexpensive and so much value for money. Why would I waste 10 times the price and buy anything else?

Lei founded Xiaomi in 2010 with seven engineers and technologists, including the alumni of Google, Motorola and software company Kingsoft. Yunfeng Capital Management, the US$1.1 billion private equity fund of Alibaba’s chairman Ma, is a Xiaomi investor. Alibaba owns the South China Morning Post.

China’s Xiaomi in talks with US, European carriers in global push

Lei is driven, decisive and passionate about technology, several people who have worked with him or received his investments said in interviews with the Post.

More than anything else, the native of Hubei province said he was motivated by the belief that Chinese manufacturers could cast off the stigma as makers of cheap, low-quality bootleg products.

Putting his belief into practice, Xiaomi started life producing smartphones with specifications found on the best overseas models, selling them at less than half the price.

“When Samsung and LG were selling their phones at 5,000 yuan (US$795), most Chinese vendors were pricing their products at less than 1,000 yuan, and using the cheapest technology. But Lei started with the most expensive specifications,” said Wang Xiang, a former Greater China president at Qualcomm.

Shopping for a chip supplier, and armed with nothing more than an idea, Lei made a passionate two-hour presentation to Wang in 2010. Wang was so convinced that he assigned several dozen engineers out of Qualcomm’s 100-strong team in China to support the start-up, he recalled.

The first Xiaomi smartphone, the Mi 1, featured Qualcomm’s top-of-the-line Snapdragon S3 Dual Core processor, with front and back cameras, was priced at 1,999 yuan (around US$317), less than half of what imported Android phones were selling for. The Mi 1 received more than 300,000 pre-orders in the first 34 hours when it went on sale in 2010.

Wang would later persuade his San Diego-based employer to join in the second round of Xiaomi’s fundraising and become an investor, an unprecedented move by the chip maker.

“I brought the Qualcomm CEO to meet Lei, who once again gave us a speech that lasted for hours,” Wang said. “He sold his idea to us, and brainwashed us to become Xiaomi fans.”

Three years after launching Mi 1, Lei hired Hugo Barra, Google’s product spokesman for Android, as vice-president of international operations. Wang himself was so enamoured of Xiaomi that he left Qualcomm to join the start-up in 2015, and was promoted two years later to senior vice-president, replacing Barra last year when the Brazilian left Xiaomi to start his own venture.

Since Xiaomi’s revenue took off, Lei has turned into the elder statesman of Chinese tech investments, with both Xiaomi and his venture fund Shunwei Capital investing in an estimated 450 companies in China and overseas. India would be Xiaomi’s major stepping stone to the world, with a US$1 billion plan to nurture 100 Indian start-ups over five years.

“He has a very grand vision of whatever he wants to do,” said Mandeep Manocha, founder of Manak Waste Management in New Delhi, which operates the Cashify online service for selling used smartphones and laptops, backed by Shunwei. “He believes that if you want to build something, you need to think about it on a large scale, and figure out how to outpace the competitors quickly, so you can become the No 1 in the market.”

All eyes on ‘Apple of China’ as Xiaomi debuts at biggest mobile show

Pitching to Lei requires deep knowledge and presentations that cut to the chase with no extraneous padding, said Madhusudan Ekambaram, co-founder of Finnovation Tech Solutions in Bangalore, India, which operates an online instalment store for students called KrazyBee.

“He had a poker face, and we didn’t know whether he liked our business idea or not,” Ekambaram said, recalling his pitch to Lei and two dozen Xiaomi business and technology leaders. “We did not know how to react during the meeting. ”

But Lei lived up to his reputation. After KrazyBee’s afternoon pitch, Lei’s team responded the next morning with a commitment. Xiaomi and Shunwei would participate in the third round of KrazyBee’s fundraising.

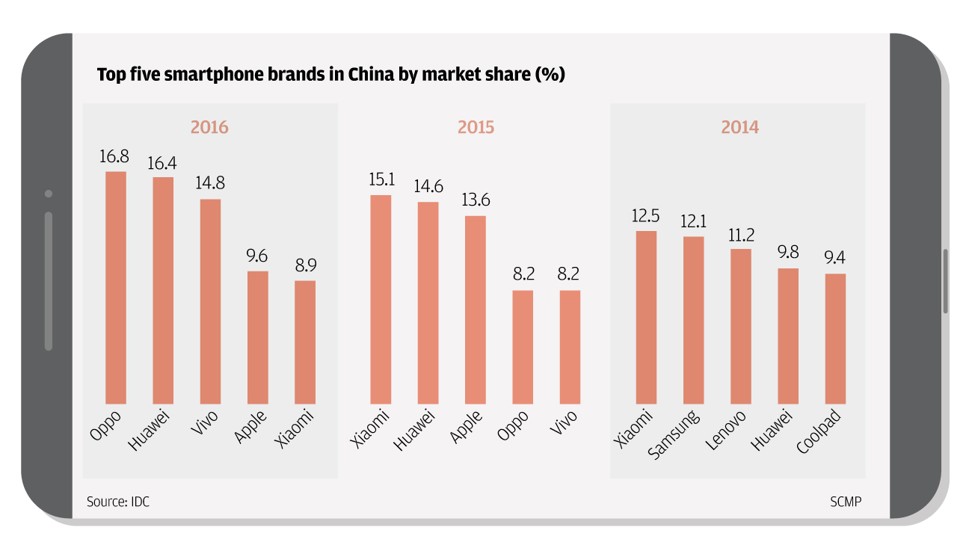

Lei’s decisiveness filters through Xiaomi’s culture. The journey from start-up to 100 billion yuan in global sales was completed several years ahead of schedule, and Xiaomi went from market entrant to No. 1 in India in three and half years.

Up to 70 per cent of Xiaomi’s sales came from seven models of smartphones, 20 per cent from scores of household and appliance products made with partners, and an estimated 10 per cent from internet services.

Lei’s corner office is stacked full of knick-knacks – visitors’ gifts, from an American football to gadgets – some of which are his muse for innovation and improvement.

He is most animated when discussing technology. He would grab random items off his shelf to make his point about Xiaomi’s workmanship. There’s a Xiaomi ballpoint pen in Mac white, selling for 9.9 yuan, with a faux rose gold-plated premium version going for 25 yuan.

Ideas emanate from his product development team and from customers’ feedback, Lei said.

The Xiaomi Mi Power Strip was Lei’s idea. Selling for 49 yuan in China and US$17.77 on Amazon, the three-socket extension cord comes with three USB ports and is made of flame-retardant material, again in Mac white. The sockets are configured for the three-pin Australasian and the two-pin Europlug standards, but unusable for UK plugs.

During an interview, he would summon Xiao Ai, the 169-yuan (US$27) smart speaker, to demonstrate its artificial intelligence. Speaking in Chinese, Xiao Ai would provide an accurate readout of the current temperature, but got lost with the air pollution index.

“We need to take a gradual approach in the globalisation of our products,” he said. “We need to strengthen the control of our quality and manage our brand. So we have to control our growth pace before we build up the capacity to manage our quality and our brand.”

Hong Kong last year pushed through the biggest amendments in the city’s listing rules in decades, to let technology companies with multiple classes of shares and pre-revenue biotech firms raise capital.

I have no interest to be Jobs II or Bezos II. I think Xiaomi’s business model is very different from theirs, even if it has absorbed some of their uniqueness

China’s securities regulator showed its goodwill by approving a 27 billion yuan IPO application by Foxconn Industrial Internet in five weeks, inclusive of a weeklong public holiday, record speed compared with the normal two years required for listings in China.

Xiaomi eyes US smartphone market despite Huawei’s own setback

Lei would not comment on any aspect of Xiaomi’s IPO plans, including the destination or the fundraising amount.

“I have no interest to be Jobs II or Bezos II,” Lei said. “I think Xiaomi’s business model is very different from theirs, even if it has absorbed some of their uniqueness. Ultimately, the Xiaomi business model is an innovation of our own.”

With additional reporting by Iris Deng and Coco Liu in Hong Kong