Climate change: can Hong Kong businesses cope with a direct hit by a super typhoon at high tide?

- Large swathes of Tsim Sha Tsui, Central, Wan Chai and Causeway Bay would have been inundated in case of a direct hit, non-profit says

- Hong Kong faces challenge of strengthening infrastructure without overspending on over-the-top facilities, official says

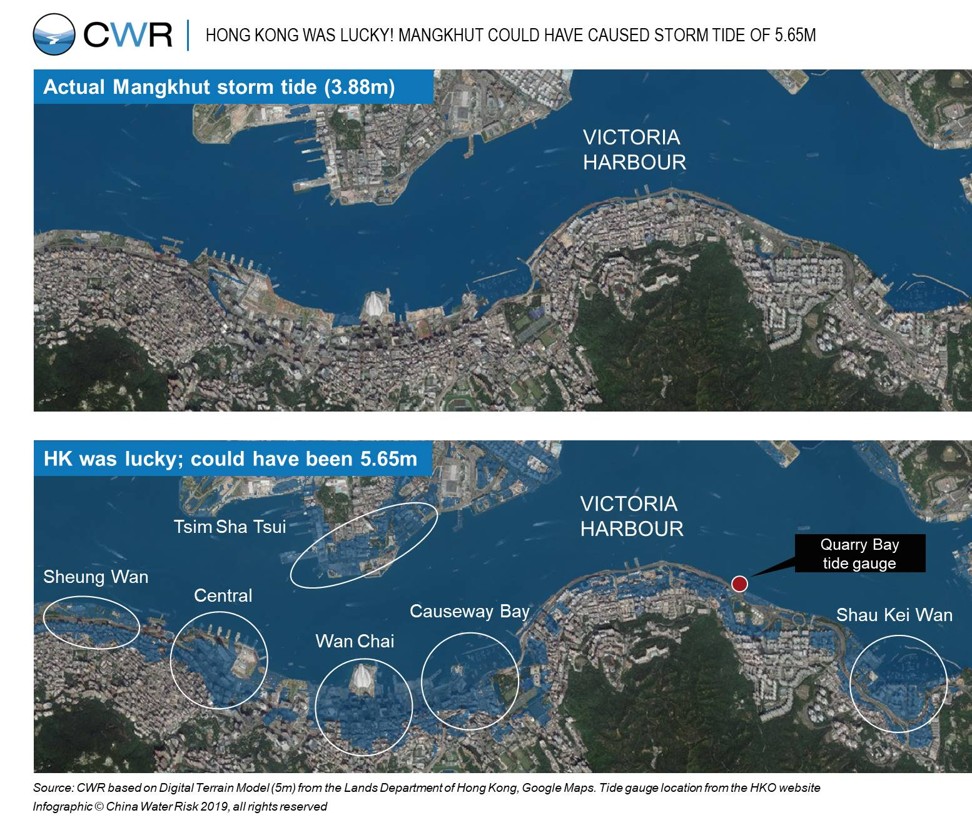

According to researchers at China Water Risk (CWR), a Hong Kong-based non-profit initiative, large swathes of the business districts of Tsim Sha Tsui, Central, Wan Chai and Causeway Bay would have been inundated. The initiative used a digital terrain model to show areas lying up to 5 metres above sea level would have been flooded in this scenario.

“Hong Kong was lucky. Mangkhut could have caused a storm tide [in Quarry Bay as high as] 5.65 metres, which would have inundated Central … storm surges could have reached past Des Voeux Road [500 metres from the sea front], which would have been extremely costly and disruptive,” CWR said in a recent report.

“The natural inclination is to ignore these warnings as being alarmist, too distant … this certainly seems to be the prevailing attitude among governments and companies in the GBA,” it said.

Hong Kong joins the ranks of Guangzhou, Shanghai and Tianjin in mainland China, Kolkata and Mumbai in India, as well as Tokyo and Bangkok as cities most vulnerable to storm surges in Asia, according to the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). More than 90 per cent of the global population exposed to tropical cyclones lives in these areas.

The IPCC, supported by thousands of volunteer scientists globally, is tasked with providing an objective and scientific view of climate change linked with carbon dioxide emissions.

Governments and businesses in Hong Kong and its neighbouring cities – spared from devastation arising from super typhoons in 2017 and last year – need to step up their preparations as the impact of climate change escalates in the coming decades, according to the panel.

“Even if efforts to mitigate emissions are very effective, extreme sea-level events that were rare over the last century will become common before 2100, and even by 2050, in many locations,” the IPCC said in a report released in late September. “Without ambitious adaptation, the combined impact of hazards like coastal storms and very high tides will drastically increase the frequency and severity of flooding on low-lying coasts.”

More severe storm surges and waves will be generated by rising sea levels, as global warming expands the oceans’ volume and causes glaciers and icebergs to melt. This is besides storms with greater intensity fuelled by warmer seas.

According to the IPCC, the global average sea level might have risen by about 22 centimetres since the turn of the 20th Century, as average temperatures rose by about one degree Celsius. Sea levels could rise by 40cm to 80cm this century if the global temperature increase is contained at 2.5 degrees over pre-industrial levels by the end of this century.

But based on emissions reduction commitments made so far by countries under the 2016 Paris Agreement, a 3.2 degrees increment from pre-industrial levels is anticipated by the panel. This means much more aggressive cuts to carbon emissions are needed for the world to make the well below 2 degrees increment goal set out in the agreement.

And the United States’ withdrawal further undermines the agreement as well as the global fight against climate change.

Mangkhut was the most intense storm to affect Hong Kong since records began in 1946, and CWR is not alone in raising the alarm.

New Jersey-based non-profit climate science research company Climate Central said in a report late last month that land supporting the homes of about 93 million people in China’s eastern and southern coastal regions – especially Shanghai and the adjacent Jiangsu province, Tianjin and the Pearl River Delta – will fall below the elevation of an average annual coastal flood by 2050. The Pearl River Delta is home to nine cities that Beijing wants to integrate with the two special administration regions of Hong Kong and Macau under the GBA, which aims to rival the US’s Silicon Valley.

Climate Central, whose findings were published in scientific journal Nature Communications, based its estimates on an improved global elevation data set it produced using predictive analytics, which showed that “coastal elevations are significantly lower than previously understood in many areas”, it said.

Charles Yonts, head of power and environment, social and governance at brokerage CLSA, meanwhile, said recently that companies such as Hongkong Land, the largest office landlord in Central, Hutchison Port Holdings Trust, a major container terminals operator in Hong Kong and Shenzhen, and Hong Kong flag carrier Cathay Pacific Airways, had yet to disclose their preparation for such risks.

The vast majority of Hutchison’s cargo handling sites in Kwai Chung in Kowloon and Yantian and Huizhou in Shenzhen would be flooded by a storm tide of 5.87 metres, while Hongkong Land could see nine of its 12 office buildings in Central – worth US$32 billion last year – affected by such an event, according to CWR’s model.

Elevating yard areas, rebuilding warehouses and erecting flood walls at ports in the GBA could cost as much as US$1.5 billion, CWR said, citing estimates by sustainability consultancy Asia Research Engagement.

Mangkhut damage costs to soar, with insurance companies set to bear the brunt

A spokesman for Hutchison Port said the company“acknowledges the issue of climate change” and has been in “regular consultation with industry experts to ensure its assets – existing and future projects – are built in accordance with international standards vis-à-vis the safety and sustainability of terminal operations”.

Hongkong Land too said it was aware of the impact of climate change and rising sea levels on its operations, and believes these were “best addressed through collaboration and actions taken by both industry and government”.

Cathay redirected queries about climate change preparedness to Hong Kong’s Airport Authority, whose spokeswoman said it was “well aware” of potential storm tide flooding risks, and that it would activate established contingency measures should land links to the airport be disrupted. The construction design of its runways followed recommendations based on the IPCC’s latest assessment of climate change impact, she added without giving details.

The authority was also building a sea wall that would reach 6.5 metres above sea level, according to CWR.

MTR Corporation, which runs the Airport Express rail service, was “working closely with the government to ensure [its] transport networks are resilient and adaptive to climate change”, a spokeswoman said.

The challenge the Hong Kong government faces is strengthening its infrastructure with a sufficient margin of resilience, without overspending on over-the-top facilities, according to an official.

Look at Mangkhut havoc to see impact of climate change

“Climate change is an imminent global problem, but the forecast of its effects is full of uncertainties, including political and human factors,” a spokesman for Hong Kong’s Drainage Services Department said. “If the most severe climate change scenario is adopted for drainage system planning, resources including money and land will be spent unnecessarily on overly designed drainage infrastructure.”

The department, which works with the Civil Engineering and Development Department (CEDD) to tackle storm surge risks, has adopted a moderate climate scenario by the IPCC for drainage infrastructure resilience planning.

This assumes global temperatures will rise by 1.6 degrees to 1.7 degrees between 2031 and 2050 compared with pre-industrial levels, rising by 2.5 degrees to 2.9 degrees by the last two decades of this century. The worst-case scenario will be covered by emergency preparedness and future infrastructure upgrades, the official said: “The government will keep abreast with the latest global development on climate change and regularly review the design standards … to allow sufficient flexibility for adapting to different future climate scenarios.”

The risk of storm surges, while potentially devastating, needs to be put into context, said Chan Sai-tick, senior scientific officer at Hong Kong Observatory.

A 5.65-metre storm tide was a worst-case scenario that has a “rather low probability of occurrence” and has never been recorded in the past 150 years, he said in an interview. Chan, however, did add that such a surge would have been possible had Mangkhut not been weakened crossing Luzon Island in The Philippines, and had it hit Hong Kong directly during high tide.

The CWR model also projects that at least half of Macau’s casinos could be affected by extreme storm tides by as early as 2030.

In the flood-prone Inner Harbour area, the Macau government erected a 2.1-kilometre flood wall to withstand storm surges of up to 4.8 metres, besides installing water pumping and storage systems. As an additional protection measure, it also announced a long-term plan to build a 650-metre wide removable tidal gate system that will allow vessels to pass and can withstand 5.8-metre storm tides.

This system, higher than Hato’s maximum recorded storm tide of 5.58 metres, would be enough to cope with a “once-in-200-year” storm emergency, the government said.

Casino operators Wynn Macau, MGM China and Sands China declined to comment, while Galaxy Entertainment Group and Melco Resorts & Entertainment did not respond to queries.

On the mainland, in neighbouring Guangzhou, its government this month announced a plan to expand and reinforce embankments totalling 13 kilometres, and that it would raise nine discharge sluice gates to protect four islands prone to storm surge-induced river water inundation.

Back in Hong Kong, the CEDD engaged consultants in April this year to conduct a comprehensive review of low-lying coastal and windy locations that had been hit by Mangkhut’s storm surge. The review is expected to be completed in April 2021, after which improvement works and protection measures will be formulated.

Businesses too need to plan for such a crisis. “Insurance companies and property underwriters are modelling for catastrophic risk. Any complacency in the broader business community could threaten the ability to recover from extreme weather events,” Simon McConnell, Hong Kong managing partner at law firm Clyde & Co, which has published reports on climate change liability risks, said.