It's high time Beijing kicked its addiction to GDP numbers

Gross domestic product figures on the mainland are so political the state news agency Xinhua is prepared to rewrite history over them

Making a fetish of anything is foolish, but making a fetish of gross domestic product is worse than that. It's not only unwise, it's unhealthy.

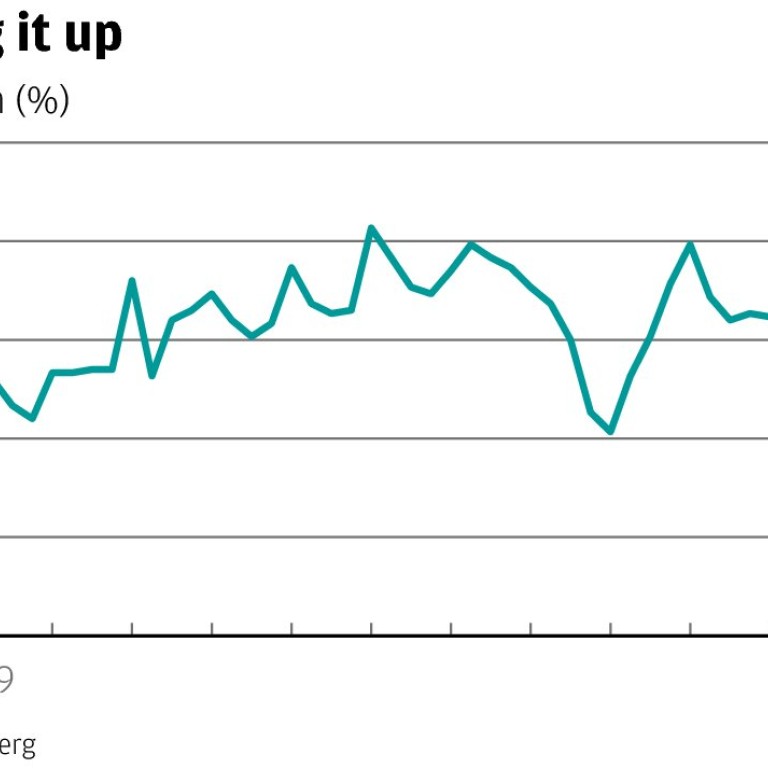

For years ministers drew a line in the sand. Growth must be supported above 8 per cent, they said, in order to sustain full employment.

Any failure to keep GDP growth above that level would be regarded as political failure, and a potential threat to the Communist Party's rule.

So when activity slowed after the 2008 international financial crisis, the Chinese authorities pulled out all the stops, ordering the country's banks to lend as much money as it took to stimulate the economy and maintain growth.

They succeeded, but increasingly China's leaders have come to realise their obsession with GDP is both distracting and destructive.

Alas, kicking the GDP addiction is going to be tough. Despite all his talk of economic reform, last week Premier Li Keqiang promised that Beijing would do whatever it takes to keep GDP growth above a minimum floor level.

Then the state news agency, Xinhua, quoted Finance Minister Lou Jiwei as saying that growth could dip below 7 per cent this year. It seems that number was too low for comfort, however. Over the weekend, Xinhua quietly revised the quote, with Lou now saying there was "no doubt" that China will achieve growth of 7.5 per cent this year.

In fact, China's growth has so far out-run the pace laid down as sustainable in Beijing's current five-year plan that if the economy were to hit the GDP targets, growth would have to slow to no more than 6 per cent a year over the next three years.

Yet, as Li's pledge and the hasty revision of Lou's remarks demonstrate, if growth were actually to slow to such an extent, it would be considered a political disaster.

This focus on GDP numbers does no one any favours. Described as a measure devised so that economists could avoid thinking, GDP was developed during the 1930s depression, and came into its own during the second world war as a gauge of how many guns, ships and planes an economy was able to produce.

But GDP measures quantity, not quality. Although it tells you how much stuff you are churning out, it says very little about the health of your economic development.

For example, you can stimulate GDP simply by paying workers to dig giant holes in the ground and to fill them in again. That will allow you to hit your growth target, but it will add nothing of any value to your economy.

Equally, GDP fails to account for costs including environmental and health damage. So you can record impressive GDP growth if you don't limit pollution, even though you may be eroding the value of your natural assets and storing up heavy medical costs for the future.

(A few years ago, China's State Environmental Protection Administration did try to factor pollution costs into the country's GDP figures. But when it found that including environmental costs would have reduced growth by at least a third, the attempt was quickly discontinued.)

Simon Kuznets, the US economist who originally developed the idea of GDP, understood the measure's limitations. "Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between its costs and return, and between the short and the long run," he warned. "Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what, and for what."

It's advice Li, Lou and the rest of the Beijing leadership do well to listen to.