Beijing sets irreconcilable economic targets for 2014

Much needed reforms will slow down the economy, so a pledge of stable growth is at odds with priorities of tackling debt and overcapacity

Last week China's leaders met to set their economic policy goals for next year.

According to a statement issued late on Friday after the meeting's conclusion, Beijing's main policy objectives for 2014 will be to maintain output growth at a stable rate while implementing key economic reforms.

Unfortunately, these two aims - stable growth and structural reform - are mutually exclusive. China can have one or the other next year, but not both.

The official release did not put a number on Beijing's target for gross domestic product growth in 2014. That's likely to be announced at March's meeting of the National People's Congress (although it may well be leaked in advance).

However, the statement's emphasis on "stability and continuity in macroeconomic polices" hints that policymakers are aiming for growth of 7.5 per cent next year, the same target as they set for 2013.

At the same time, China's leaders stressed the need to press ahead with key reforms next year, pledging to "focus on debt risk prevention" and on "resolving the overcapacity problem".

This is where their policy aims appear to diverge. In recent years Beijing has maintained China's rapid growth rates by keeping interest rates low and encouraging state sector industries and local governments to borrow heavily in order to fund massive investments in new plant and infrastructure projects.

The policy succeeded in keeping growth rates high while much of the developed world slumped into recession. But the price has been a heavy one.

Over the last five years China's debt level has ballooned from 120 per cent to around 200 per cent of GDP.

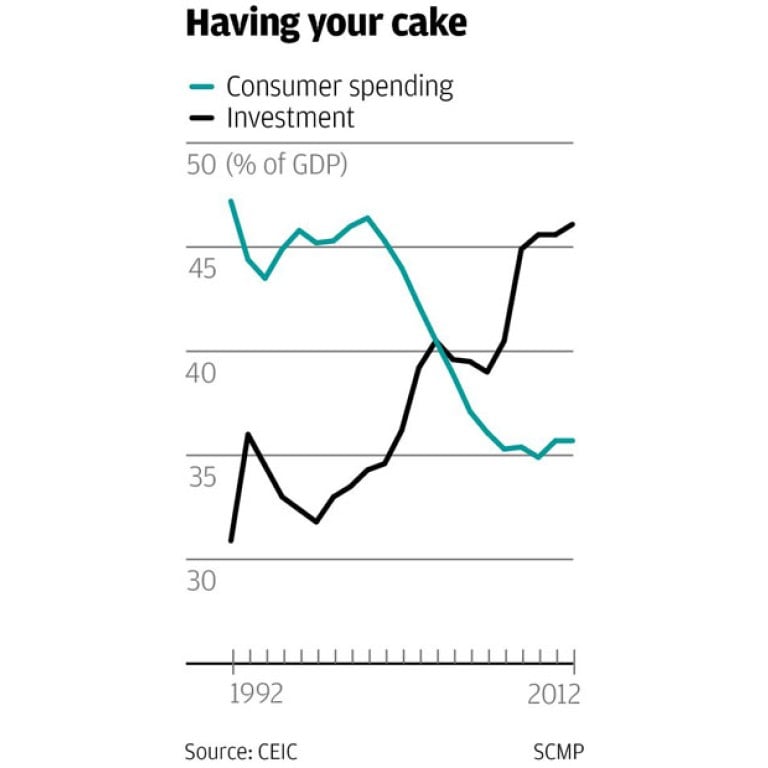

That debt expansion has financed an unprecedented investment boom, which last year saw fixed capital formation climb to a record 46 per cent of China's total economic output (see the chart).

The trouble is that much of that capital has been poorly allocated. Countless billions of yuan have been poured into building unneeded roads, bridges and airports which see little or no traffic.

Even more has been pumped into heavy industrial sectors that were already suffering overcapacity. Between 2009 and 2012, China's glass-making capacity, for example, grew by 50 per cent. Following the investment binge, China now has 1,650 shipyards, while the city of Tangshan in Hebei boasts a greater steel-making capacity than the whole of Germany.

As a result, in many industries China's productive capacity now exceeds its demand by 25 per cent or more, an overshoot which has pushed the industrial sector into deflation since early 2012.

Naturally, unused tollroads and falling prices make it ever more difficult for local governments and state companies to service the huge debts they ran up to fund their new investments.

In short, the economy's returns on investment are falling, which is why growth rates have slumped from double-digit rates three years ago to less than 8 per cent today. Under the current model, China would need heavily to step up its borrowing and investment levels each year just to maintain the same rate of growth.

That's unsustainable, of course, which is why the authorities want to limit debt and tackle overcapacity before they run into an enormous economic crisis.

But if enacted, their reform programme must inevitably mean a slowdown in growth. Beijing would like to switch to an economic model driven more by consumer demand. However, that's not going to happen overnight, or even next year.

Household consumption is already rising rapidly in real terms, but from a relatively low base, which limits its contribution to overall growth.

What's more, if the authorities do indeed curb debt expansion and begin eliminating industrial overcapacity, the incomes of millions of households will suffer, which will slow the growth of consumer demand.

In other words, if Beijing goes ahead with its promised reforms, controlling debt and cutting overcapacity, then economic growth must slow steeply. Conversely, maintaining stable growth would mean forgetting about reform.

You can't have your cake eat it.