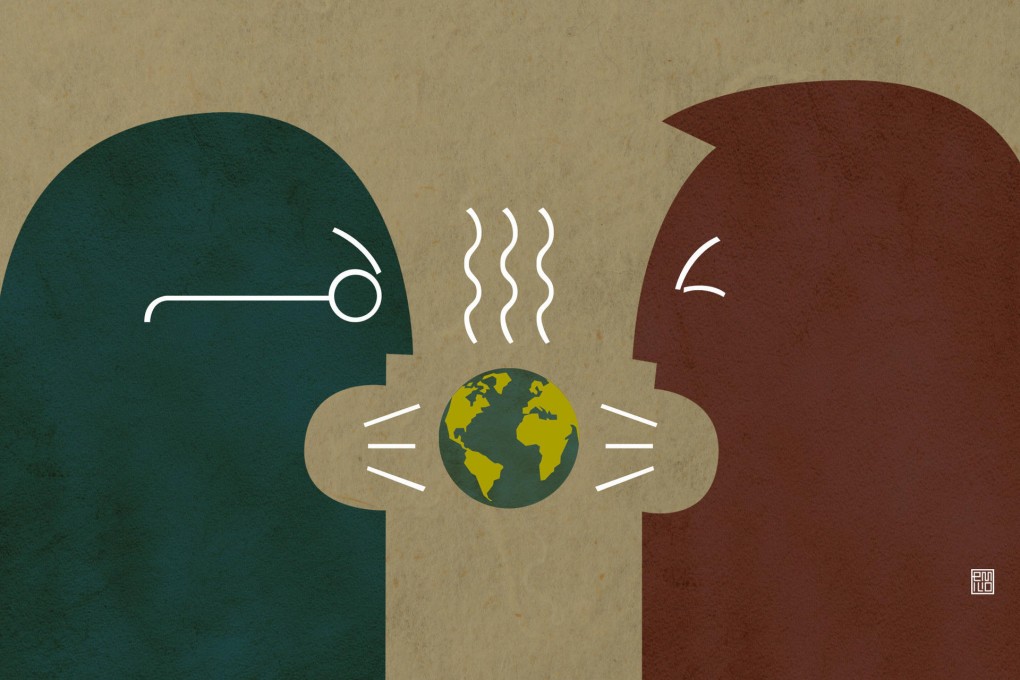

China-US co-operation would reduce hot air on climate change

Bilateral action by the two largest polluters, China and the United States, is the most effective way to unlock the global impasse on climate change

Lots of fossil fuel has been burned over two decades as government officials and sundry others have sped across the globe to frequent United Nations-sponsored meetings aimed at tackling catastrophic climate change.

The latest gathering of this kind brought together nearly 700 officials from 169 governments, along with a couple of hundred observers, who huddled in Bonn last week for four days.

The West grew rich with no constraining thoughts about climatic degradation

Despite all the miles travelled in the 22 years since the first of these internationally co-ordinated efforts to do something about global warming was initiated at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the distance between nations on effective co-operation is enormous.

The Bonn meeting aimed to make progress on establishing a new agreement next year to effectively extend the commitments of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.

The protocol, which entered into force in 2005, legally bound 37 developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but the rest of the world had no such obligation.

And that's the fundamental reason why international discussions on joint action to date have been so fraught and unproductive - they have all been about competing views on where the burden of responsibility for dealing with the problem should fall.