Warmongering cannot be allowed to damage continued progress made in global trade

Post Xi-Trump summit, the adults in the room on global trade must put their heads together to begin the process of building a robust defence of the overall merits of liberalising international trade and investment

Even on this Easter weekend it is probably premature to hope that US President Donald Trump has had a sudden “Road to Damascus” revelation that will call off his dogs of trade war, receding the January fears of imminent and potentially catastrophic conflict.

Instead, I suspect, his testosterone has been distracted by the challenge of pummelling Syrian airp bases, northern Afghanistan mountains – and waving a big stick at Kim Jong-un.

I suppose I should be mightily anxious about this military muscle-flexing, but in spite of the extraordinary paranoid unpredictability of Kim, I sense there are a lot of experienced adults in the military strategy rooms in Washington, Beijing and Seoul, and so I can’t yet get myself to panic of any imminent nuclear conflagration.

And I had better be right, because this time next week I will be flying to Seoul for the year’s second meeting of the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC).

The worst war that I was expecting to discuss there was a trade one. And on this front, there is much to be encouraged about. Trump has tasked Wilbur Ross to spend from now until July drafting a detailed report on the true trade challenges facing the US, and how to address them.

Trade liberalisation has generated higher living standards worldwide through greater productivity, increased competition, knowledge exchange, more choice for consumers and better prices in the marketplace

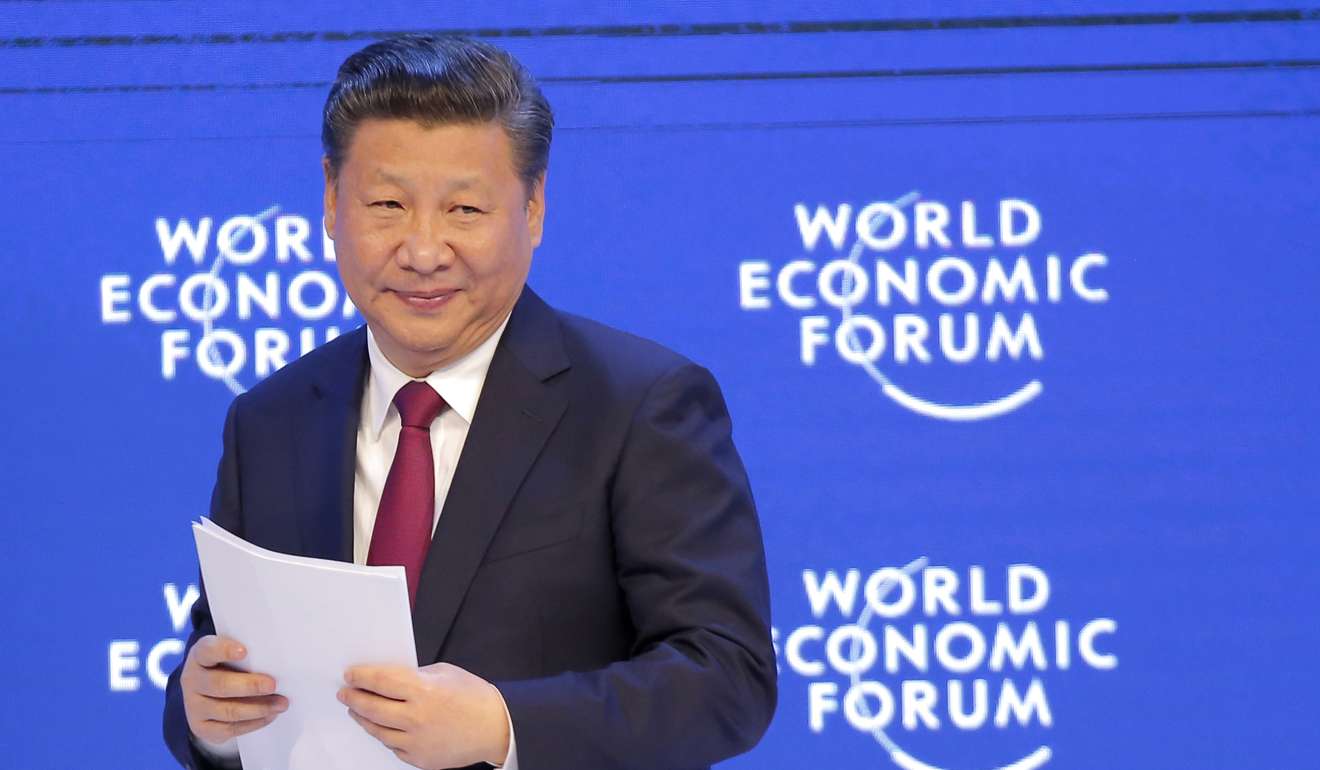

Some of his more extreme tweets have been softened by what seems to have been a modestly constructive meeting in Mar-a-Lago a week ago with China’s President Xi Jinping. Trump has at last agreed that China is not after all a currency manipulator.

This has given some of the adults in the room on global trade an opportunity to put their heads together to begin the process of building what I hope can be a robust defence of the overall merits of liberalising international trade and investment.

These include three leading global economic institutions – the World Trade Organisation, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank – which last week released a dull, dense but powerful and not too lengthy report delivering some important messages about the broad and deep benefits of global trade.

Of course, these are experts, and we know what Trump acolytes like Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro think about experts that do not hold their views.

But I am encouraged nevertheless and think their report will provide useful support and comfort to ABAC members as they gather in the South Korean capital, and prepare to express concerns to the region’s trade ministers who will meet in Hanoi in three weeks time.

The report, entitled “Making Trade an Engine of Growth for All”, provides a valuable reprise of the gains arising from trade and investment liberalisation over the past three decades and cautions that the world economy is at a critical juncture, following a decade of weak trade growth since the 2008 crash. It warns of the harm that would be done by a slowdown in trade reform and an uptick in protectionism.

It illustrates in a sometimes painstakingly dull yet expert way that trade liberalisation has generated higher living standards worldwide through greater productivity, increased competition, knowledge exchange, more choice for consumers and better prices in the marketplace.

At the same time it has lifted into the global consuming classes, communities in many developing economies that would otherwise today still be struggling with severe poverty.

The report recognises that technological change is responsible for the lion’s share of job losses that advanced economies have seen in recent decades

In the words of the WTO’s director general Roberto Azevêdo: “Trade has had a very positive impact on the lives and livelihoods of many millions of people in recent decades. I recognise that there are very real concerns, but the answer is not to turn against trade, which would harm us all.”

Apart from showing that trade leads to productivity gains and to significant benefits for consumers, especially the poor, the report recognises that technological change is responsible for the lion’s share of job losses that advanced economies have seen in recent decades.

The report at the same time acknowledges something that trade officials, economists and a large body of business leaders engaged in international trade have until recently failed properly to recognise: that the benefits of open trade have not been shared widely enough, and that adjustment to more open markets has hurt certain communities and workforces quite harshly.

At the same time, it reminds us that trade is just one factor contributing to economic change and labour market disruption, alongside other drivers such as technology and innovation.

At some length, the report calls for governments to review labour practices and “transitional programmes” that can help the unemployed get back on their feet and mitigate adjustment costs due to trade, and technology change.

Drawing on research by the 31-economy OECD, it notes that economies with comparatively generous policies towards the unemployed, and on adjustment back to work – like the Scandinavian economies – show very positive attitudes to trade liberalisation and regional economic integration.

By contrast, those with limited unemployment and adjustment funding – like the US and Britain – have seen the greatest level of recent public disquiet over open trade. The US ranks 29th out of 31 in terms of transitional adjustment, for example.

A recent WTO, IMP World Bank report ...fails to recognise the benefits of open trade have not been shared widely enough, and that adjustment to more open markets has hurt certain communities and workforces harshly

The report reminds that when the US in 2009 slapped punitive tariffs on Chia for allegedly dumping tyres in defence of US tyre manufacturers, the cost was US$900,000 for each US job saved – equivalent to 22 years of salary for an average tyre worker.

In other words, the US could have gifted a 22-year payout to those tyre workers, and saved American tyre-users the punishing cost of having to buy more expensive tyres.

The report called for well-structured active labour policies, such as training programmes, job search assistance and wage insurance, that can facilitate the reintegration of displaced workers into the job market, and passive labour market programmes, such as unemployment benefit and income support, which help to stabilise working families in the short term until those who have lost their jobs can get back to work.

While Hong Kong is nowhere specifically mentioned in the report, I reckon the points it makes are as relevant to us as they are to anyone. Our transitional stress due to technology change, and the radical transformation occurring in the Pearl River Delta, call for much more clever attention than we have seen from our recent leaders.

Our ABAC meetings in Seoul could be more than usually instructive – so long as we can keep the dogs of war at bay.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view