Outside In | Your next meal depends on 14 choke points in the world’s food supply transport chain

‘The most alarming message is not that these 14 choke points exist, but that the danger of something going wrong is extremely high – and rising by the year’

In 2000, China imported 10 million tonnes of soya beans. Today, imports have risen to 80 million tonnes – about 40 per cent of the world’s soya trade – and by 2025 it is expected to be 106 million. In the process, soya has overtaken maize, wheat and rice as the world’s most traded food commodity. From the farm cooperatives of Iowa and North Dakota to the smallholders in Sorriso in Brazil, wealth has been built on China’s burgeoning appetite for the nondescript green bean.

But the very success the world’s food exporters in meeting the need being created by a rising middle class of Chinese meat eaters is creating a wholly new challenge: rising worldwide reliance on food trade has created deep dependence on the road, rail and sea routes used to get farm products like soya to places like China.

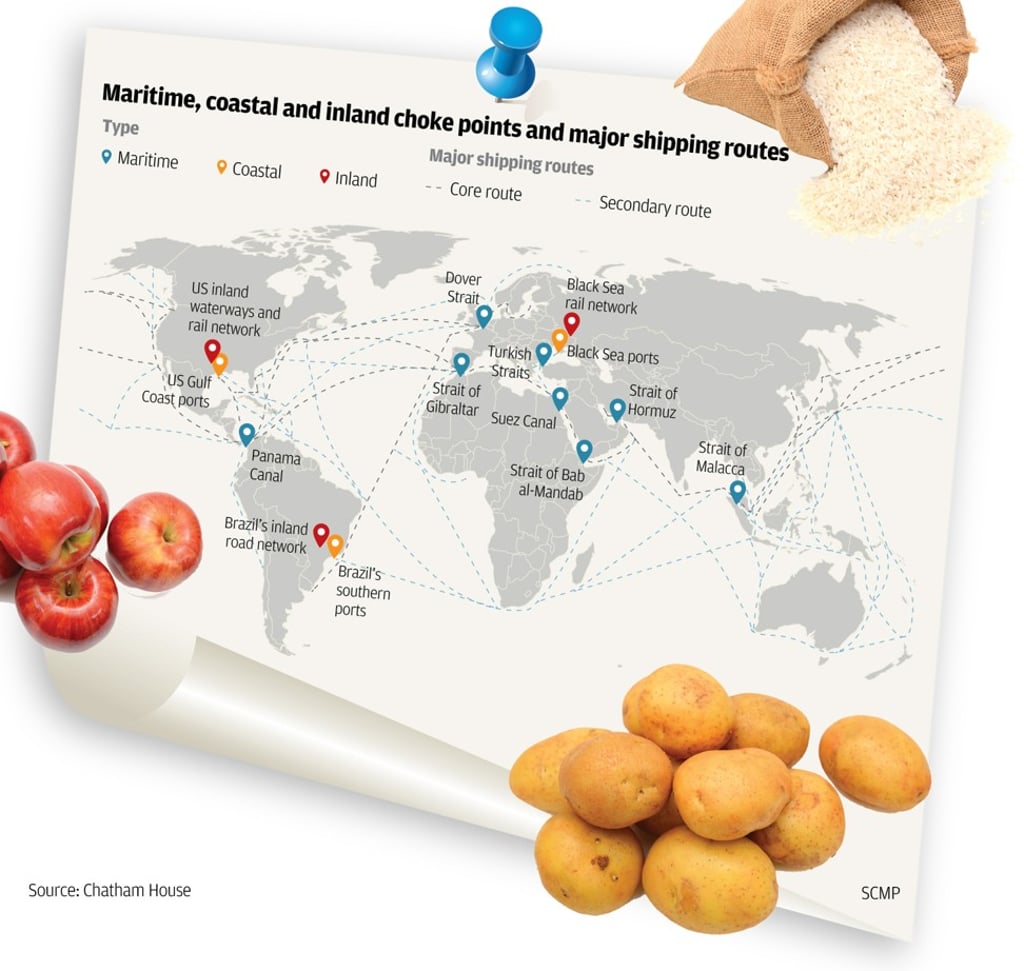

This has created crucial “choke points” across the world – a total of 14 in all – where, if anything goes wrong, millions will go hungry and even starve.

In a fascinating new study from Chatham House in London, which perhaps for the first time examines in detail the vulnerabilities of the world’s food supply chains, the most alarming message is not that these 14 choke points exist, but that the danger of something going wrong is extremely high – and rising by the year. They are “likely vectors and potential epicentres of systemic disruption”, the report claims.