The Italian job

The raging optimism of equity bulls was stopped in its tracks last week by shock Italian election results

Just when investors thought it was safe to get back into equities, the euro-zone crisis returned with a vengeance last week, with Europe's benjchmark Euro Stoxx 50 dropping 3 per cent on February 26, its worst daily loss since mid-2011. The severity of the correction following Italy's shock election results suggests the bulls were caught by surprise.

The question now becomes whether the equity bulls can recover their poise and continue to buy; or whether the "Italian job" has fatally undermined their carefully constructed optimism.

In other words, should we use the dip as a buying opportunity now or should we wait for further market consolidation?

My view is that equities are set for a decline. But before I get to that, let us look at the bulls' case for optimism for stocks, be it the Hong Kong market or globally.

The base case is predicated on three compelling views: that mainland growth will accelerate; that central bank activism (read quantitative easing, money printing) in the United States, Europe and Japan will continue; and that the big macro risks that plagued 2011-12 - such as the mess that surrounded Greek elections and concerns over the US fiscal cliff - are diminishing.

Let's take each in turn. Mainland stocks took a hit last week with the unexpected slump in China's purchasing managers index (PMI), a keenly watched economic indicator. While a large part of the decline reflected seasonal distortions, the index also reflected a deeper-than-expected slowdown in output that analysts now believe could continue into the second quarter. One or two data points do not tell the full story about China's economy, but the decline reminded investors not to take the country's growth for granted.

Equity markets also stumbled in mid-February after the market interpreted comments released by the Federal Reserve, that hinted the central bank may soon be winding up its quantitative easing programme. The third round was launched in September, and kicked off the recent rally in global equity markets.

The merest hint of a so-called exit strategy among central banks is enough to give the market heart palpitations, so in testimony last week before the US Congress, Fed chairman Ben Bernanke went out of his way to calm those fears.

But, as we all know, quantitative easing cannot last forever.

The Fed subtly communicated this fact in its minutes, forcing equity investors to contemplate the day when the market is not propped up by the monthly injection of US$85 billion-plus of fresh credit.

All of which brings us neatly to Europe and the vexing implications of Italy's election results. Is it really as bad as the markets initially made out? In fact, I think it really is. The majority of Italians voted against austerity.

Under such circumstances, the European Central Bank will find it difficult continuing with its own version of quantitative easing, which has done much to calm market jitters about the euro-zone sovereign debt crisis. But if euro-zone electorates appear set to ignore the diktats imposed by the European Union, where does that leave Germany's leverage and by extension, the ECB's credibility? With such profound questions going begging it appears only a matter of time before the fuse of euro-zone calamity reignites.

All of which is a way of saying I suspect the equity correction under way has further to run.

Given the head of steam built up by the bulls over the past few months, it was always going to need a combination of sell catalysts to slow them down; which is exactly the scenario we're looking at now.

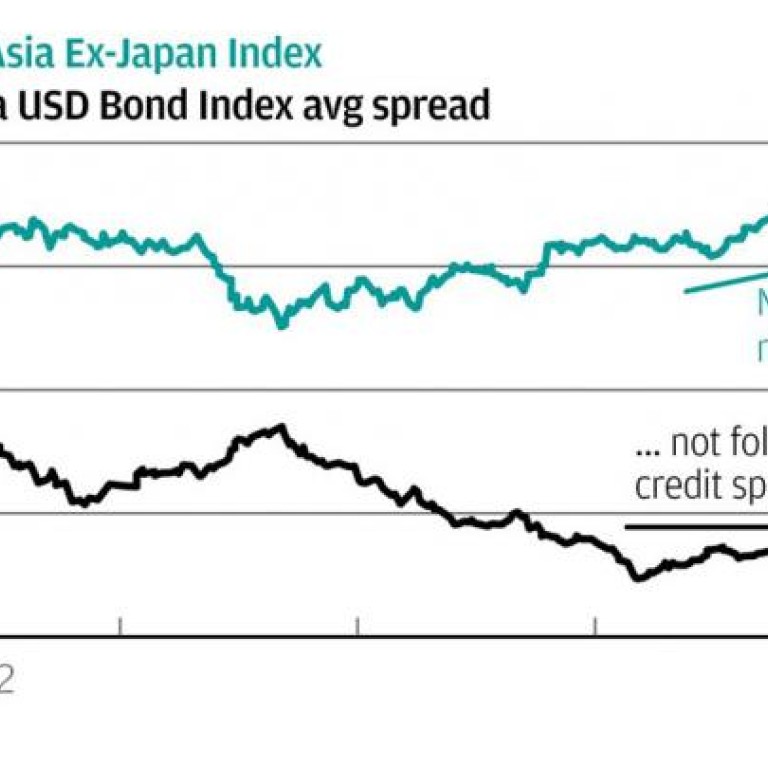

But don't just take my word for it - look at the less-than-exuberant behaviour of Asia's credit spreads. Credit spreads measure the yield paid on corporate bonds over a low-risk benchmark, typically government bonds. Higher spreads suggest investors see greater risk in corporate bonds and therefore require more yield to buy the debt.

Credit spreads are a kind of anxiety index for investors. When the spread goes up investors are expressing a more fearful view of the outlook for corporate bond issuers.

Usually spreads and equity markets trade in negative relationship to each other. When spreads rise, share prices fall. In recent months however, both spreads and equity markets have trended up (see chart). Analysts called this phenomenon "divergence". It's unusual and unlikely to last. Either equities or bond spreads will decline, and my bet is that it will be equities.

John Woods is the chief investment strategist, Asia-Pacific, for Citi Private Bank