How climate change makes winner and loser of the world’s vineyards

European wine production has fallen by 14.6pc last year because of ‘adverse weather conditions’, according to global industry trade group OIV

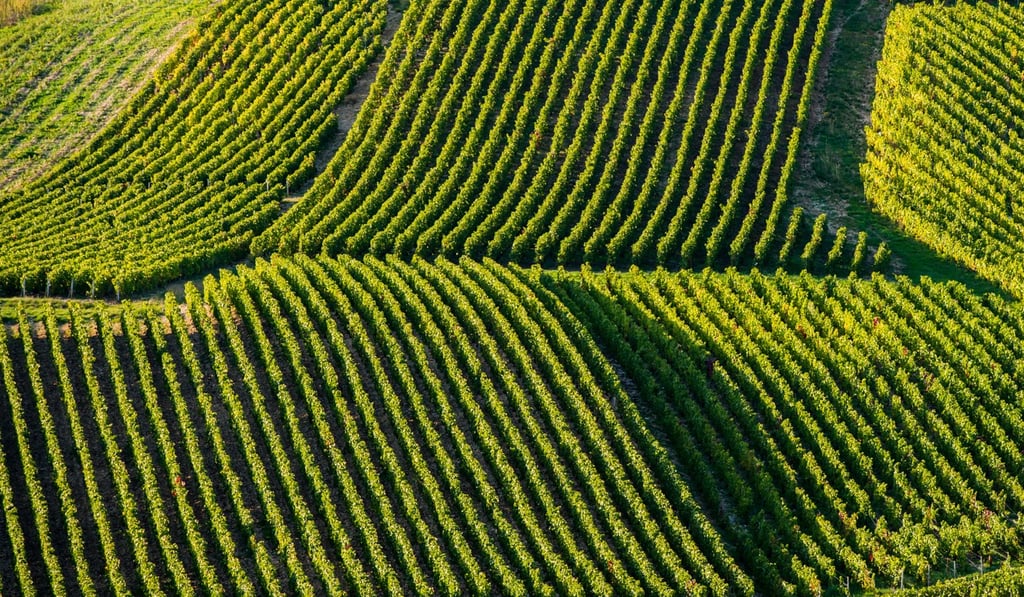

A wine’s success is often predicated on its terroir – whether it is from one of the most renowned vineyards in Bordeaux or Napa or a less auspicious producer in southern England. Wine depends as much on the plot of land from which it was plucked as it does on the method in which it was made. Until recently, the effects of a changing climate are causing dramatic impact.

The 2017 wildfires that swept through northern California, incurring an estimated US$3 billion in insured losses were an example, though the vast majority of wine producers were relatively untouched. Nonetheless, the region’s wine producers recently met to discuss collective crisis management for the coming year. Less noticed but perhaps far more damaging was the drought that destroyed 40 per cent of last year’s crop in Provence, France, the world’s premier source for rosé wine, a favourite among millennial drinkers.

Figures by the Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin, a global industry trade group, recorded a 14.6 per cent drop in European wine production in 2017 from 2016, blaming “adverse weather conditions” in Europe’s main wine producing regions. Meanwhile, global consumption has been rising, adding price pressures for wine drinkers.

A disruption is transforming the wine world, thanks in part to climate change. Wine watchers believe the most renowned regions in the world – Bordeaux, Napa Valley, Tuscany – are in peril, while other previously derided grape-growing regions – England, Canada, China, New York – are hailed as the future of wine.

“If you pan back and look at the big picture, how we make wine hasn’t changed since Roman times,” says Julien Fayard, co-founder and winemaker at Napa’s Azur, who trained at France’s grand Chateaux, including Lafite Rothschild. “But what has changed is the way we do it, the machines we use, the chemicals, what we know about varietals and how different techniques can affect the final product. Also, the climate in which we grow the grapes.”