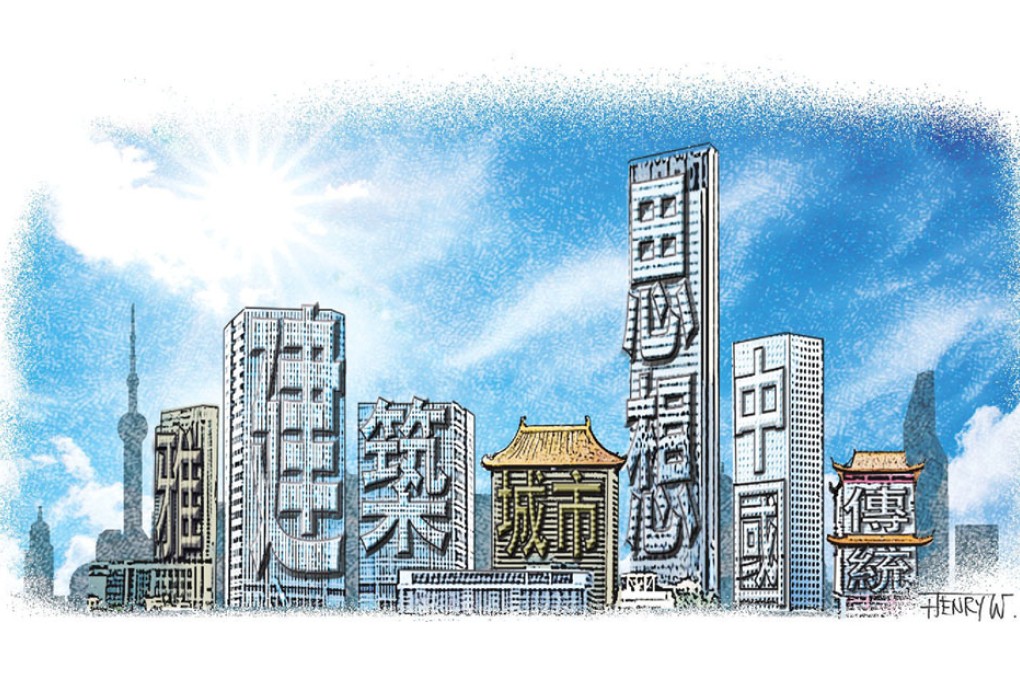

How Chinese cities lost their elegance

Shiqiao Li says a reason for the bad architecture that litters Chinese cities is a failure to connect the cityscape with the essence of traditional Chinese thought, as seen in its writing system

In the past 100 years, China has marginalised its own intellectual and institutional frameworks developed over 2,000 years. It happened through the successive revolutions and reforms in the 20th century, sometimes for good reason, sometimes as acts of defiance.

Legitimate or not, it happened amid tremendous pressure to acquire the technological, scientific and institutional efficacy that the West had demonstrated. The sweeping changes included the ways in which Chinese cities were designed and constructed, thus defining in many important ways our daily lives.

Today, one question lingers: have we overdone it? One thing is clear: in marginalising Chinese tradition and falling short of wholesale importation of Western cultural and political ideals and institutions, Chinese cities have become, in one sense, the scrapyard of half-hearted emulations and acts of resistance, appearing to be neither here nor there.

In the meantime, traditional cultural and political ideals haven't just gone away; in their marginalised position, they reappear quietly and persistently in modified forms. For instance, traditional courtyard houses and gardens, so exquisitely described in literary works such as the Dream of the Red Chamber, returned in the forms of the work unit ( danwei) and the residential compound ( xiaoqu). The act of circling and walling spaces in cities corresponded to the ward system that had been central to the traditional Chinese image of cities, at least since the Tang dynasty.

It is, of course, both impossible and unnecessary to undo the development of scientific knowledge and cultural institutions in China over the past 100 years. We should imagine the Chinese city in multiple dimensions; there is an excellent chance today to reintroduce dimensions of Chinese culture, not as something canonical, vernacular, exotic, supplementary or alternative - as they are routinely portrayed - but as something equal and legitimate, among all possible ideals of knowledge and politics.

As the French theorist Bruno Latour argues, imagining in a singular dimension of purified "scientific knowledge" is both illusionary and damaging; the root of our current global financial crisis and our suicidal exploitation of the environment lies in the mistaken belief in the fundamental divide between human and nonhuman. This divide has been constructed through the purification of scientific knowledge into ideology.

Chinese thought has never conceived this ideological purification of scientific knowledge, and thus offers an amazing chance to revise our way of life, perhaps to liberate us from oppressive monetary systems and relieve the pressure to further destroy our environment.