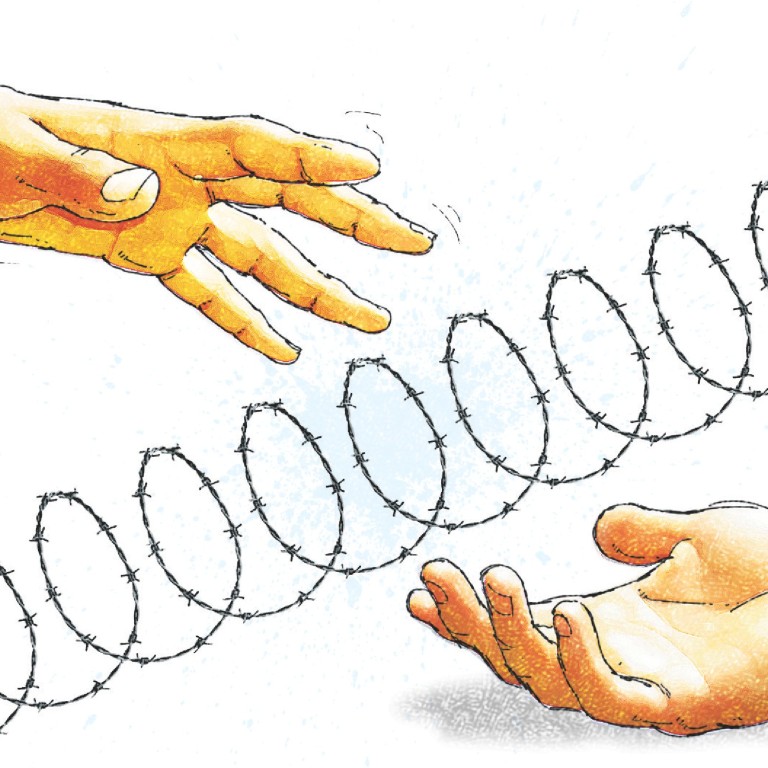

In China, trouble is too often the reward for being a Good Samaritan

Mattie Bekink says soul-searching over the Chinese capacity to help strangers - renewed by a recent case on the Shanghai subway - should open debate on the treatment of Good Samaritans

As reported last week, a Chinese crowd on a subway in Shanghai ran away from a fainting foreigner. He slumped over, eventually fell to the ground, and was left alone in the subway car. This has once again sparked debate about the callousness of the Chinese public and whether modern society has somehow made China's citizens unwilling to aid those in obvious need.

This soul-searching is ongoing. It was perhaps never so anguished as after the death of Wang Yue - a two-year-old girl who was hit by two vehicles in Guangdong and ignored by at least 18 passers-by before anyone assisted her - but the capacity of crowds in China to turn a blind eye to basic human suffering is nothing new.

I passed out on a subway in Shanghai in 2001. It was rush hour, so I was standing: a smartly dressed 21-year old foreign woman commuting to my office. It was a full subway car, but nobody broke my fall, causing me to land on my face. When I was treated for my injuries, I was told the only reason I still have real teeth is thanks to a permanent retainer which spread the impact across my mouth.

In my case, people didn't flee the car. But when I regained consciousness, lying on the floor in a small pool of my own blood, I noticed we were stopping and the doors were opening. I asked, in Putonghua, whether this was Dongfang Road, my stop. The responses from my fellow passengers were to shout to each other, "Hey, that foreigner speaks really good Chinese!" One person did address me, telling me my Putonghua was great. I managed to read the signs outside the car and crawl off the train myself.

Thankfully a colleague was in another carriage on the same train and ran over to assist me, alerting the station employees as she did so.

At the time, I felt as though needing to have my jaw reworked was the lesser of my injuries. I was hurt that, even after spending a good portion of my young life in China and speaking the language, I was still seen as a foreigner first, a human bleeding on the floor and in need of assistance second. The case of Wang Yue, however, makes plain that it is not just foreigners who cause crowds to turn away.

The public discourse on these cases tends to take a philosophical bent, focusing on questions of common decency, modernity's destruction of traditional values, or whether increased wealth has caused a decline in compassion and morality. But a more nuanced view may require examining Chinese law and its treatment of Good Samaritans.

My first exposure to how the law can influence citizens' behaviour came well before law school. As a teenager in Beijing, I vividly recall a trip to the countryside with my family.

As we were driving along a winding mountain road, we suddenly came across a crowd peering over the edge. Since we could drive no further, we also got out to see what had happened. We were informed that a small truck had lost control and tumbled over the cliff. The gathered crowd informed us they were "watching the passengers die".

I was horrified, but a Chinese family friend with us explained that the people were too afraid of being implicated in the deaths to assist the people below. Most of the crowd were poor farmers without a sophisticated understanding of the law. They were not callous or bad people, but they knew the risks and were fearful of getting involved.

China is notorious for its poor treatment of Good Samaritans. Individuals who have tried to help injured people can be accused of injuring the victims themselves. There have been instances where courts have found those who offered assistance liable. In 2006, for example, a 65-year-old woman was trying to board a bus in Nanjing when she was knocked down and broke her hip. A young man went to assist her and took her to hospital.

The woman later said the young man had knocked her down. He said someone else caused her fall and he assisted her out of the goodness of his heart. She sued him and he was required to pay her about 45,000 yuan (HK$56,000) to compensate for her medical expenses, bodily injury and emotional suffering.

Cases like the young man's are a serious deterrent to Good Samaritans in China. There is an understanding that good deeds can lead to punishment. Despite the national outcry over the death of Wang Yue and the release of a video showing people seeing the child but refusing to help, 71 per cent of participants in a national survey thought that the people who didn't aid the toddler were afraid of getting into trouble themselves.

Wang Yue's case prompted the Guangdong government to consider developing a Good Samaritan law. Such laws offer protection to people who assist those who are injured, ill, or in peril in order to reduce bystanders' hesitation to assist for fear of being sued or prosecuted. In some countries, these laws even encourage citizens to offer assistance. On August 1 last year, China's first Good Samaritan law came into effect in Shenzhen. This is a promising first step and it can serve as model to other jurisdictions in China.

Before we call the Chinese callous or lacking compassion, we need to understand the legal context in which they live. The failure to aid a seriously injured toddler or a fainting foreigner may not be a commentary on the character of a nation's people as much as it is an illustration of how its laws influence (in)action.

The latest incident has already sparked discussion in China. Let this be an opportunity to advocate greater legal protection for Good Samaritans nationwide rather than bemoan an alleged lack of morality.