Beijing has failed to honour its promise to Hong Kong

Michael Davis says the pan-democrats have every reason to reject any political reform proposal based on a Standing Committee decision that clearly violates the Basic Law

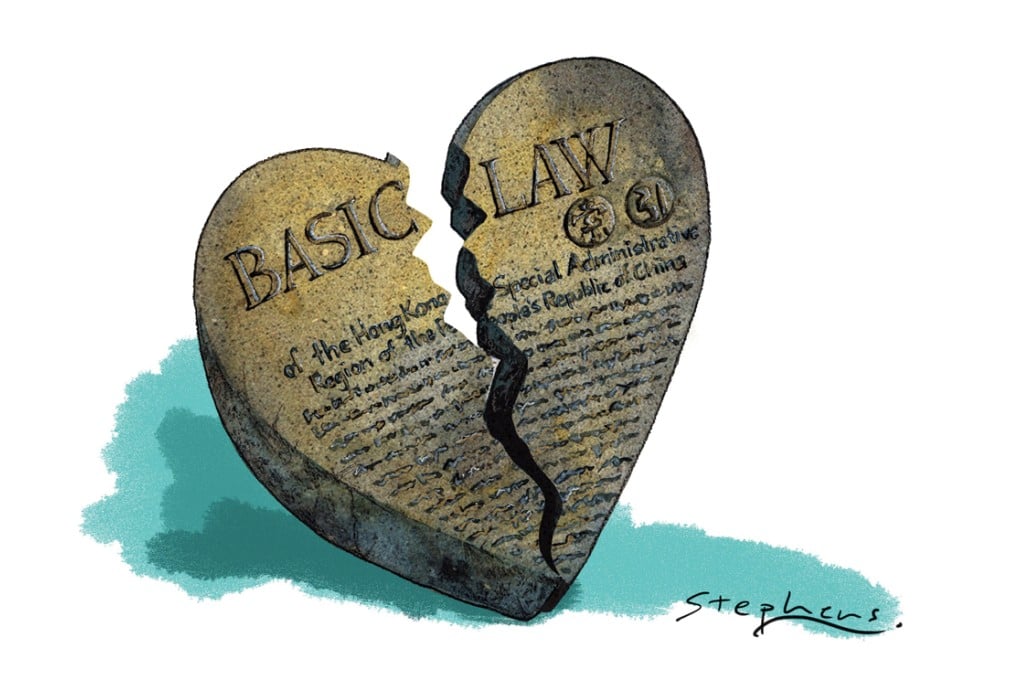

Beijing's decision on universal suffrage marks a dark day in Hong Kong history. The shortcutting of its firm commitments in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law signals a broken trust. Both sides have long struggled in their arranged marriage, agreed on in the Joint Declaration and sanctified in the solemn vows of the Basic Law.

By requiring a majority vote in a highly unrepresentative 1,200-member pro-Beijing nominating committee, the central government is effectively blocking candidates from the more popular pan-democratic camp. Any token legislative manipulation in the make-up of that committee will not avoid this failing. A limit of two or three nominees further secures this unfortunate blockage of the voters' free choice.

In the recent white paper, Beijing effectively disavowed its international legal commitments in the 1984 Sino-British treaty by claiming that the 12 articles of the Joint Declaration were merely 12 principles crafted by China before the declaration. Along with exclusive authorship, Beijing claims exclusive authority.

Accordingly, Beijing argues that the Basic Law can now be interpreted or amended as it prefers, presumably without constraint. Beijing has long claimed such a power in principle but the legal constraint in using such power is now little evident.

In Sunday's decision, the central government took full advantage of this claimed authority, giving the Basic Law's solemn commitment to universal suffrage an interpretation nobody but Beijing and its supporters would recognise. It is unfortunate that neither Hong Kong officials nor the anointed Hong Kong National People's Congress delegates who attended the Standing Committee proceedings adequately represented Hong Kong concerns. Their practice has been to lecture Hong Kong on Beijing's concerns.

The liberty of interpretation Beijing claims not only denies Hong Kong its promised universal suffrage, but also puts in doubt the city's greatly cherished rule of law. Such wide official discretion on such fundamental human rights matters cannot be consistent with the rule of law.