China's future lies in its people

David Tang, who has travelled on the mainland for 35 years, says to become a superpower, China must realise its future lies in its citizens, not in state power that operates in opacity

Today, we Chinese in Hong Kong feel thoroughly Chinese, and regard ourselves as living in part of China. Even foreign residents in Hong Kong must be very conscious of living in a Chinese city. But not so long ago, it was not the case. I remember distinctly the Chinese television soap called , in which a mainlander was caricatured as a country bumpkin, frowned upon as ignorant, unworldly and awkward.

It was with contempt that the Hong Kong populace regarded the mainlanders. Nor did it like the way the British colony was being handed back to the motherland. It is easy to forget today that all the tycoons were trying to persuade the British government to return Hong Kong sovereignty to China. Of course, precisely those tycoons who expressed scepticism then are now professed and ardent patriots!

But all that is history, and I do not intend to dwell on it. Nor would I dwell on my very first visit to China nearly 35 years ago, climbing the highest peak at Huangshan , when I felt distinctly Chinese with an acute sense of homecoming. Suffice to say that, at the time, I had not appreciated that China was at an absolutely critical juncture. The death of Mao Zedong , whose terrible legacies of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were finally beginning to subside, had effectively placed China in a vacuum.

Thank God we had Deng Xiaoping , who extraordinarily transformed the whole nation with a tiny economic experiment that was almost laughable with hindsight, at an ugly small town across the border of Hong Kong called Shenzhen.

But where do we go from here? What are the next 30 years going to bring? It is inevitable that our destiny in Hong Kong will be totally dependent on the destiny of China. So I might share with you some thoughts on the factors which will determine the next generation of China, drawing on my knowledge and experiences there from my 30-odd years of travels to all the major cities as well as remoter parts.

Consider first the very basics of land, air and water in China. Land: there are only 900 square metres of arable land per inhabitant, which is less than 40 per cent of the global average. Even more alarming is that wholesale rural areas are being turned into urban cities.

Air: totally polluted and appalling. It got so bad that, last summer, the Chinese authorities asked foreign consulates to stop publishing "inaccurate and unlawful" data on air pollution - which was a direct reference to the quality measurements posted on Twitter by the US Embassy in Beijing, which registered descriptions such as "crazy bad" and "beyond index".

Then there is water. The over-extraction of ground water and falling water tables are huge problems in China. The exploitation of dams and other irrigation infrastructure has almost halted the Yellow River's natural course, threatening to dry up the entire river valley.

Therefore, with regard to the simple essential conditions of livelihood with land, air and water, China faces enormous problems, aggravated by its vast population of 1.3 billion - and further aggravated by its demographics.

First, there is a population explosion of the older generation: by 2030, there will be 240 million aged 65 or over, with four older workers for every three younger ones. So the workforce in China is going to keep falling. With this smaller and much greyer Chinese workforce, the growth rates of the recent past are not going to be sustainable. Secondly, this swelling class of the senior citizens will undoubtedly place enormous economic pressures on China. Third, because of the one-child policy, which tends to favour boys, China will have a great male-female imbalance. The result is going to be a growing population of unmarried and frustrated young men. Fourth, the one-child policy has also meant that, for this generation, there are no more brothers or sisters, no more aunties or uncles, no more nieces and nephews, which goes directly against the traditional Chinese family structure of relying heavily upon blood relatives at home and in business.

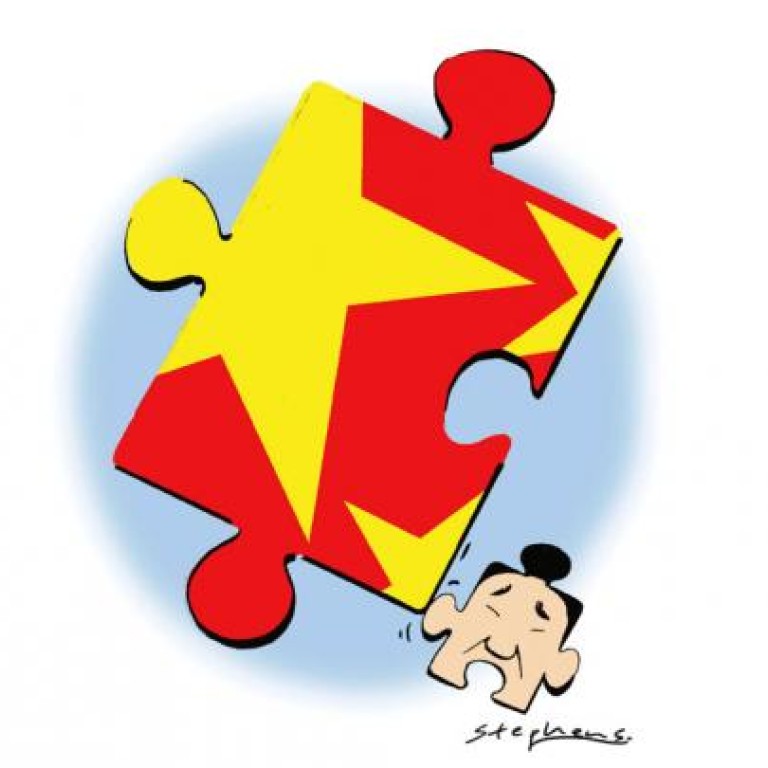

But perhaps the most critical question on China's advancement rests with the leadership, or the seven members of the Standing Committee of the Politburo. So little is known about how these few work together, or even what they think, or how they come to their conclusions. In all the major decisions, there is a blanket of opacity, which has not changed since the Communist Party took control on the mainland in 1949. This has created an enormous amount of mistrust, and, not surprisingly, there are continual protests over abuses of power, involving much bribery and corruption and social injustices. There seems to be a total disconnect between government and the people. This dysfunction can never be the basis of a great nation.

But what I would most like to highlight is the plight of the individual. Far too often, we have conferences and articles about China as a country. Yet seldom do we focus on the individual.

It is all very well to talk about the progress of the Three Gorges Dam, but how about the plight of the million people who have been displaced?

It is all very well to talk about the great 2008 Olympic Games - with the diversion of water into Beijing for the enjoyment of visitors and for the world to see. But how about the places from which the water had to come, namely Hebei and Shanxi provinces, which have been devastated by drought and severe shortages?

It was exactly 100 years ago when China became a republic with the promise of democracy - bringing to an end 4,000 years of dynastic rule. Maybe China needs another 100 years to secure real democracy and achieve the status of a superpower. After all, it took America roughly 200 years to become a superpower from an impoverished beginning. Meanwhile, to put it mildly, there is a little bit of homework to be done.