Jake's View | China's big spenders on infrastructure must generate better returns

Fixed capital formation stands at a record high of 46 per cent of gross domestic product in China. A free bottle of Scotch goes to the first person who can show me any country with a higher ratio.

Academics and bankers are split over whether Beijing is spending more than it should on investment, with levels far higher than rivals

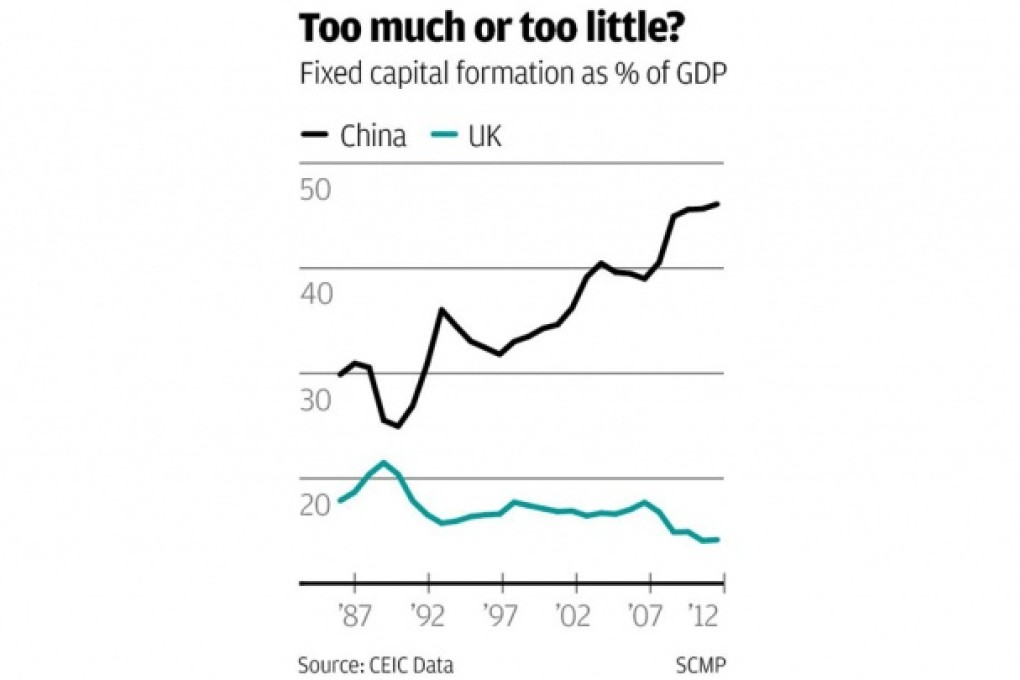

The arguments here are easily stated, and we start with the chart because a picture is always worth a thousand words.

The line at the top of the chart shows you that fixed capital formation stands at a record high of 46 per cent of gross domestic product in China. A free bottle of Scotch goes to the first person who can show me any country with a higher ratio.

The bottom line shows you the same ratio for the United Kingdom, a mere 14 per cent of GDP. I don't know if it is possible to get any lower, except, perhaps, by drinking my bottle of Scotch in one sitting. Surely this comparison suggests that China is spending too much on infrastructure and Britain too little.

But perhaps not. China is a poor and developing country. It needs to spend a great deal on infrastructure to provide the framework for greater wealth. Britain has already built its infrastructure and needs only to maintain what it has built.

Perhaps we should measure not just how much capital investment a country makes every year, but its capital stock - the value of all past investment adjusted for depreciation. Do that, we are told, and we may see that China's capital stock per person is as low as 8 per cent of America's. Thus China is still under-invested and should indeed have high ratios of capital investment.