In one household, a losing battle to keep the Chinese language alive

Kelly Yang believes the Chinese language is so important a part of her son's heritage that she won't let him lose it without a fight

Every day, I wage battle with my son. The subject of this battle is Chinese. It is a battle my own parents lost decades ago. Raising me in the US, they gave up on teaching me to read and write Chinese when I was a child. They thought just speaking the language was enough. I rejoiced until, years later, it became my biggest regret.

I wish my Chinese reading and writing were better, not so I can get a better job or make more money but to have a better knowledge of China.

The stories the local Chinese people tell me say more about the current state of China than any headline. I remember once asking a local Chinese person whether he thought the one-child policy was cruel - and he laughed at me. "What difference does it make if I have the right to have more than one? I still have to feed them, don't I? And I can't!" he said. "Foreigners care so much about rights. This right, that right. Well, guess what, you can't eat rights!"

Thoughts raced across my brain when I heard this - thoughts like, "that's indoctrination for you". Most of all, I remember thinking I need to know more Chinese. I need it to ask more questions; without it, we're getting someone else's opinion of China.

But Chinese is a ridiculously hard language to learn. Try talking to a Chinese person in substandard Putonghua and he'll immediately switch to English. Reading and writing are even more difficult. Not only are there tens of thousands of characters, but there are correct strokes, stroke order, radicals, traditional versus simplified, and countless other complications.

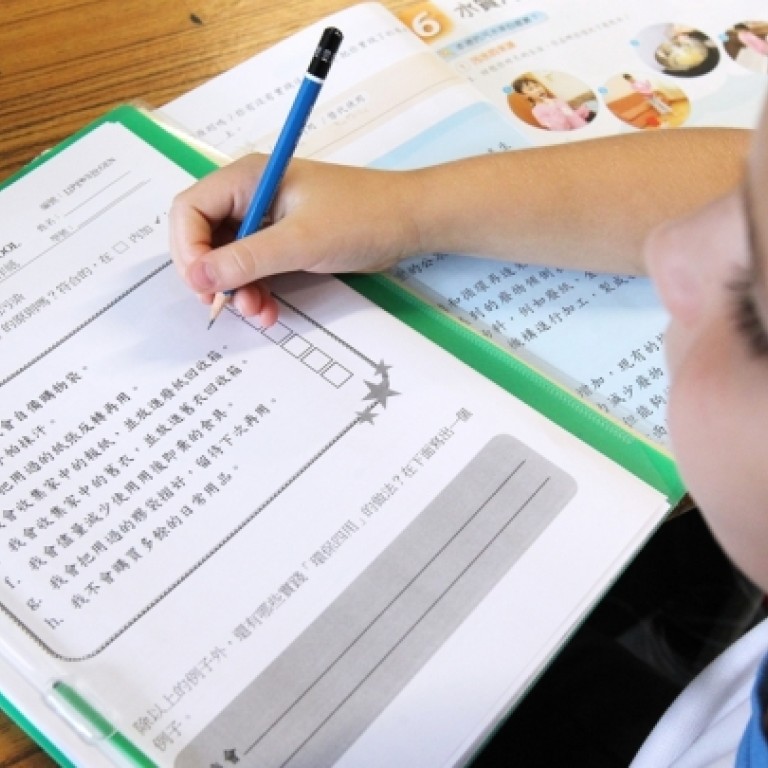

"Why can't you just let him write it however he wants?" my American husband asks me. My son and I have been sitting at the kitchen table for two hours - him, glaring at his Chinese journal, me, sighing as I erase his imperfect strokes and ask him to start over yet again. "Because I can't!" I hiss back.

Chinese is stubborn like that; there's no fun way to learn it. And if you're not going to write it perfectly, don't bother. That philosophy has been passed down from generation to generation.

To get it "perfect", we have had to change our lives. My mother moved to Hong Kong when my first child was born, mainly to teach our children Chinese. This move has come at significant cost - my father, still not retired, has had to live in California pretty much alone and my husband has had to live with his mother-in-law for the past six years.

Still, the battles continue with my son's daily chorus of "it's too hard" or "I just can't do it". At just six, he is a tough warrior with excellent debating skills. Whining, negotiating, crying and breaking pencils in frustration - these are his weapons of choice.

"Is it really worth it?" my husband sometimes asks me. It's hard for a non-Chinese speaker to understand why we're putting in such an effort.

Yet, even if one day all Chinese people can speak English, I'll still want my son to know Chinese because it's who he is; he's half Chinese. I fear if he loses the language, he'll lose a part of himself.

And so, I continue to wage battle every day to protect a king that I myself once overthrew.