Asian nations should increase dialogue over economic concerns

Simon Tay says that Asian nations, faced with capital outflows to the US and Europe and slowing growth, should step up dialogue over shared economic concerns to avert crisis

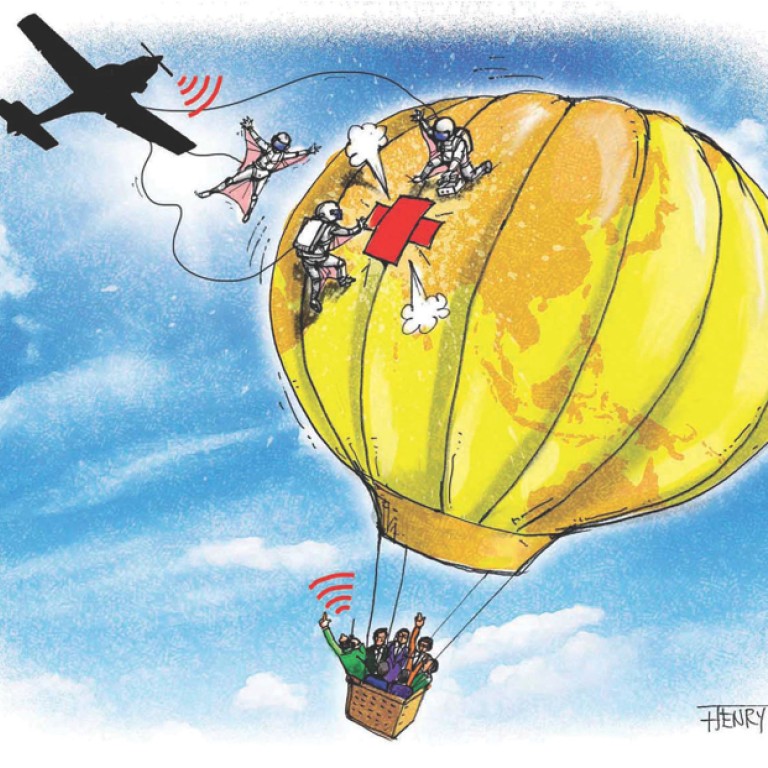

After the global financial crisis, Asia grew at more than 6 per cent each year, outperforming a troubled world. And not just China, but also India, Asean and others. While the United States and Europe floundered, the gravity-defying feat substantiated the idea of Asia's rise to close the gap with developed economies.

Now gravity seems to be catching up with Asians.

Growth in China has slowed as the new leadership rejigs policies to discipline credit and spending - much needed reform to cut wasteful projects and secure the financial system. The government targets 7.5 per cent growth. Still good, but a far cry from the days of double-digit rates.

Indian expectations are even lower after visible missteps combined with a current account deficit around 5 per cent of gross domestic product. Spooked investors and capital outflows have led to the rupee tanking.

Similar symptoms show in Indonesia with the current account deficit shooting past 3.5 per cent of GDP in the second quarter. In past weeks, the rupiah has fallen below the psychological threshold of 10,000 to the US dollar even as officials offer reassurance.

Asian capitals promise action and deny crisis. Perhaps. Triggers for the slowdown do differ from one country to another. Emerging signs, however, show macro conditions are changing, and bringing Asian economies under new stresses.

The key factor is American policy. The Federal Reserve is tightening its loose-credit spigot. This is the right response for America with the US economy looking up, but implications elsewhere bear watching.

Some start to feel the bottom and anticipate better days ahead in the US, so capital is returning the world's largest economy and, to a lesser degree, Europe. Exits from emerging markets are felt. As the big waves of easy money recede, the rocks of local problems loom more prominently.

Even kings cannot command the tide, and Asians cannot artificially stem this global financial outflow. Efforts must aim instead to adjust to the coming deceleration and ensure no crisis results.

The key responses will be domestic. At the national level, current account deficits must be trimmed or else currencies may shift to find new levels. At the sectoral level, inflated assets, especially in property, must be reined in.

Over the past 15 years, since the Asian financial crisis, most of the region cleaned up their banking sectors. The excesses of Western banks that triggered the 2008 crisis were largely avoided. But after the influx of capital in these post-crisis years, reviews would be prudent.

Reviewing regional co-operation is useful too. Legacies from the Asian crisis include the Chiang Mai initiative - now a multibillion multilateral currency swap to address balance of payments and short-term liquidity difficulties - and the Asian Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) to monitor regional economies.

These are not automated response mechanisms, however. Even if an emerging problem is signalled, governments in the region would need to take decisions. That's a potential gap - understanding and concerted action among Asian governments may not to be guaranteed.

Take China and Japan, each currently preoccupied with quite unusual fiscal policies. Beijing is tightening credit to discipline bad practices even as Tokyo pursues "Abenomics", starting with a yen quantitative easing and increased fiscal stimulus. Both must also pursue domestic reform.

The yen and yuan can affect other regional currencies, as well the propensities of Japanese and Chinese companies to invest and trade. There is, as such, good reason for dialogue. Yet Sino-Japanese political and security tensions run high over competing claims to islands in the East Asian Sea.

Japanese leader Shinzo Abe recently called for a summit to be convened between leaders but Beijing has yet to reciprocate. Tokyo's proposal is to meet without preconditions, whereas sensitivities over sovereign claims may mean that the Chinese would expect some concession.

Rather than try for a summit about fraught and quite irresolvable issues of politics and security, a dialogue about financial and economic concerns would be more acceptable - indeed, more timely. This could begin with finance ministers, rather than leaders. Such a Sino-Japanese bilateral meeting could be embedded in a larger framework convened by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

The region must brace itself for changing and turbulent global conditions. A slowdown can be managed, but if there is an abrupt stall in one country, a wider crisis could be triggered. Dialogue is needed to share Asian perspectives on the coming challenges and prepare intra-Asian co-operation for rougher times ahead.