Keep our children safe from harm by sex predators

Grenville Cross says the rise of social media and availability of online child pornography have emboldened sexual predators to prey on children, and Hong Kong's youngsters are far from immune

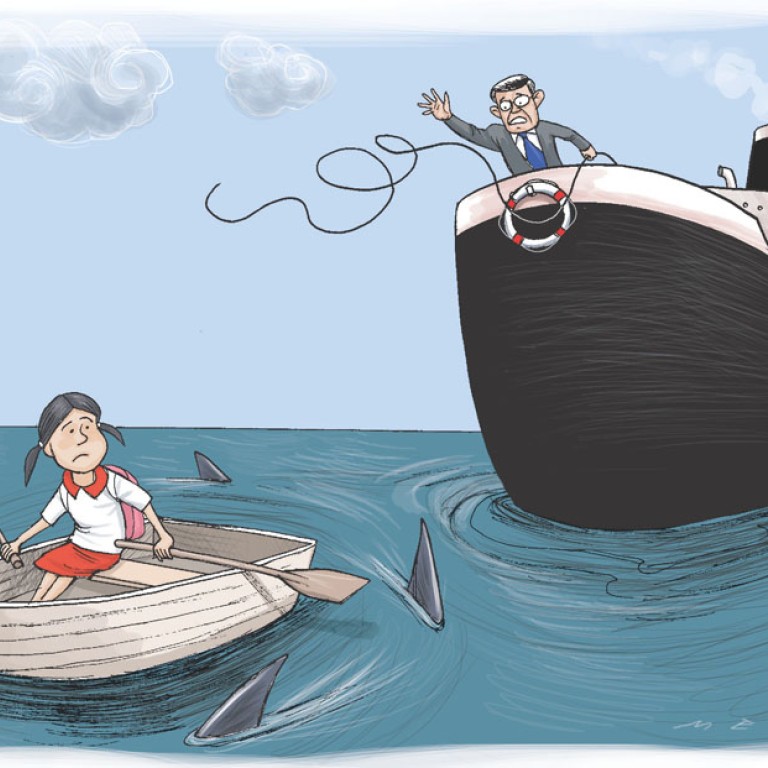

The fundamental condition of childhood," said writer Jane Smiley, "is powerlessness". When Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying delivered his first policy address in January, there were hopes it would contain the long-overdue commitment to a children's commission, to champion the interests of the child. After the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child was applied to Hong Kong in 1994, activists have campaigned for a commission, as the convention's corollary, and Leung's genuine concern for the most vulnerable people seemed to bode well.

Once the programme was unveiled, however, hopes were dashed. This was a tragedy, as the need for a powerful children's commission, such as exists in Australia, Britain and Canada, has never been greater.

Once Hong Kong has a children’s commission, it will be able to provide a voice for the child

Last month, the Census and Statistics Department revealed that the number of reported child sexual abuse cases rose to 336 last year, up from 307 in 2011 and 189 in 2004. Most of the victims were girls, and a spokeswoman said that one possible reason for the increase was "the popularity of social networking websites on the internet where children are susceptible to sexual abuse pitfalls". Predators, it appears, are targeting potential child victims through social networking sites. Online activities now pose a real threat to the young, although this has yet to be fully quantified in Hong Kong.

In England, however, it was recently revealed that Mark Bridger, who murdered April Jones, aged five, and Stuart Hazell, who murdered Tia Sharp, aged 12, had both watched child pornography on the internet. Britain's Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre has disclosed that, in 2012, there were over 70,000 photographs and videos being exchanged by some 8,000 offenders, often using encrypted websites to cover their online tracks.

The centre's chief executive, Peter Davies, commented that "there are still too many children at risk and too many people who would cause them serious harm", and there is no reason to suppose the situation in Hong Kong is any less alarming.

In 2008, when the Court of Appeal issued sentencing guidelines for the offence of possession of child pornography, the maximum penalty for which is a fine of HK$1 million and imprisonment for five years, the then chief judge of the High Court, Mr Justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li, noted that "the prevalence of child pornography only encourages paedophiles and their activities".

Although the actual production of child pornography may not be a significant problem in Hong Kong, its online availability to paedophiles undoubtedly contributes to the dangers children face.

Earlier this month, the police arrested 19 people for the alleged possession of child pornography, with 21 computers seized, and each year the number of prosecutions for child pornography offences, mostly internet-related, runs well into double figures.

There is a heavy responsibility on internet service providers to police the web, which is sometimes used for child exploitation. There has, for example, been an increase in the incidence of poor children, usually from developing countries, engaging in sexual activity on live webcams, in return for payments to organised criminal groups, who, in turn, pay off the children's minders.

Google, to its credit, has announced a zero-tolerance policy towards child sexual abuse imagery, and has pledged US$5 million to combat the problem. A global database of child abuse images is being created by Google, which will be shared with other online providers, and the technology will allow search engines and web firms to exchange information about child pornography. Pornographic images identified by child protection bodies, such as the Internet Watch Foundation, will be removed from the web.

However encouraging, this does not mean that local law enforcers can now put their feet up, and the Security Bureau must ensure that the police are fully equipped to tackle secret networks and trained to understand all their permutations.

Once Hong Kong has a children's commission, it will be able to provide a voice for the child, liaise with stakeholders, analyse data, study developments, raise the alarm, and advocate reform.

Last month, for example, British Prime Minister David Cameron announced sweeping measures to counter online pornography which, he said, was "corroding childhood". These include requiring search engines to block illegal content, greater controls on secretive file-sharing networks, creating a secure database of banned child pornography images which can be used to trace illegal content and the people viewing it, and blocking pornography to households which choose not to receive it through the use of "family-friendly filters".

Although Hong Kong can learn from elsewhere, there is a real danger that, as things stand, lessons may be missed, and, if so, children will be the losers. Of course, a children's commission cannot possibly solve all the problems, but the case for a commission to stand up for children is nonetheless overwhelming, and further delay could be fatal, at least for some.

Under its dynamic executive secretary, Billy Wong Wai-yuk, the Hong Kong Committee on Children's Rights is currently organising its "1.1 Million Children's Campaign" to galvanise the community behind its vision of a dedicated children's commission. People of goodwill will wish to provide this noble initiative with every possible support.