Financial crisis highlights need to focus on asset side of balance sheet

Andrew Sheng says the solution to financialisation is not more debt, but structural reform

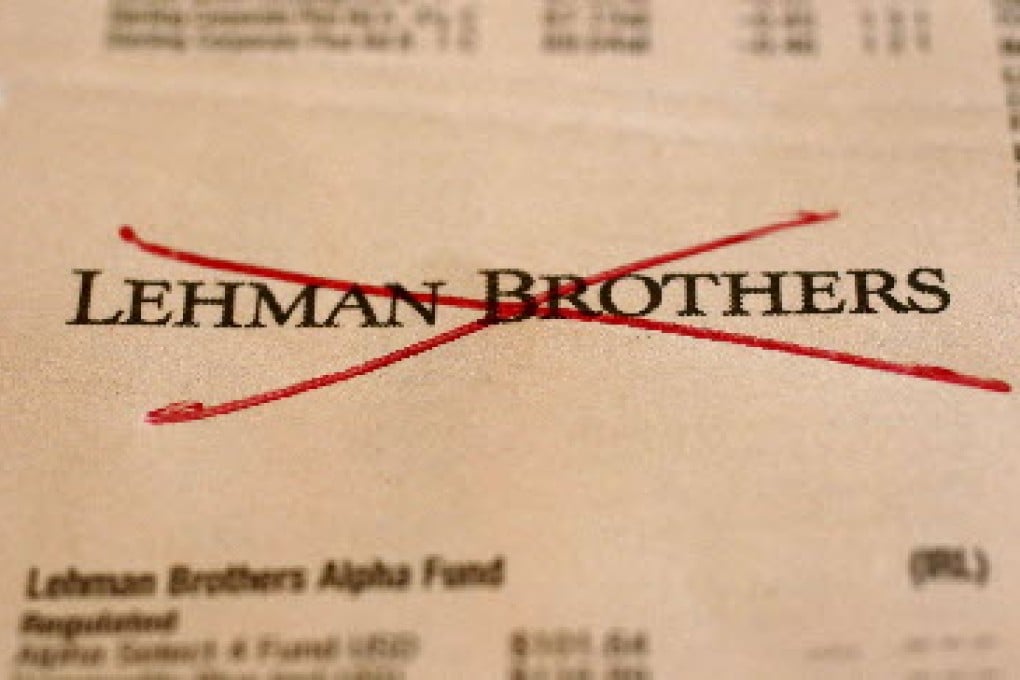

The failure of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008 marked the beginning of the end of the world's love affair with financialisation, one of three mega trends that has swept the world in the past 30 years - the others being free markets and globalisation.

Financialisation is defined as the growing importance of finance in daily activities, both at national and global levels. The effect has been massive credit creation and financial turnover in terms of scale, speed and geography that has turned finance into a power in its own right.

The dream was that financial innovation was creative, supported economic development and contributed to global market efficiency. The outcome was a massive bubble, inflated by hidden leverage and a collapse requiring massive public sector bailouts, from which the world has yet to totally unwind.

Flirting with finance diverts attention from what really matters – the real economy

Finance theory taught that risk is best diversified, but geographical diversification through globalisation disguised the fact that everything was interconnected and became more and more co-related. Borderless finance meant that no firm, no country, was an island. The failure of one hub, like Lehman, led to a cascading failure across the board.

Financial supervisors were the convenient scapegoats, for a lack of supervision, or oversight of the shadow banking-banking nexus. No one noticed that massive credit was being generated below the line, moved off the balance sheet to special investment vehicles or totally offshore.

Because it was a systemic crisis, no single banker, regulator or anyone was held personally accountable. The ensuing public anger was assuaged through massive regulations and rules as a substitute for action. The two key responses were to fight financialisation with more financialisation through quantitative easing and fight complexity with more complexity, meaning new rules. After five years of QE, a strong global recovery remains elusive.

If we agree with Nomura's chief economist, Richard Koo, that the global financial crisis is a balance sheet crisis, then financialisation has focused on the wrong side of the balance sheet. As one wise cynic reminded us, it was a crisis where, on the right side of the balance sheet nothing was right, and on the left side, nothing was left. While it is understandable that QE was a "tool of last resort", the printing of more central bank debt to prevent the bubble deflation was to use more debt to cure debt, sustainable only under lower and lower interest rates.

The threat of tapering means that if real interest rates rise, the current asset bubbles and value of sovereign debt will deflate, causing more huge losses and forcing central banks to again print more money. Real interest rates are rising despite the fact that QE is holding the so-called risk-free rate low, because the market perceives that risks and uncertainty are rising.