Fed's delay in tapering QE is short-term fix

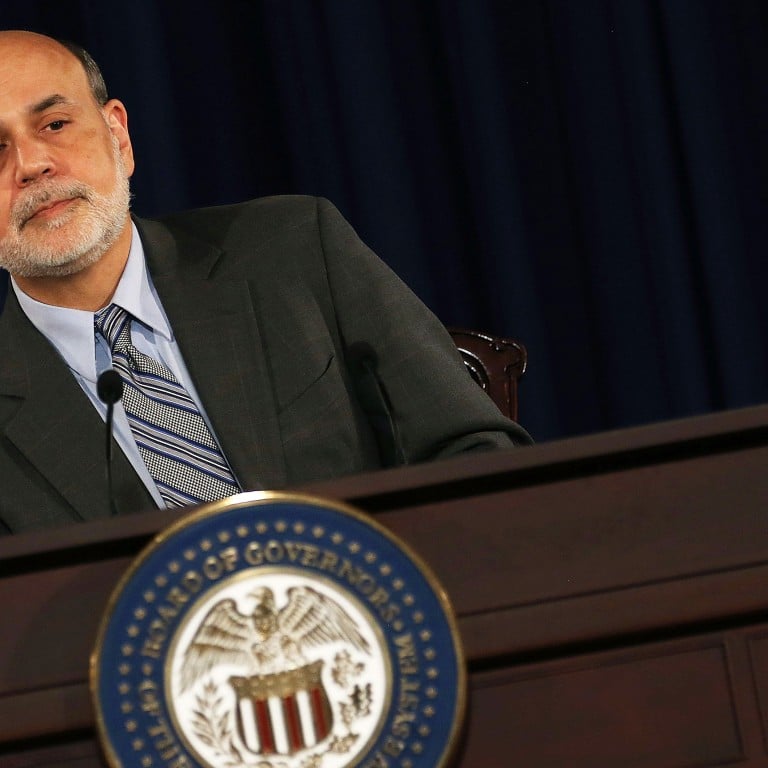

Financial markets had a pleasant surprise this week when the US Federal Reserve held off its widely expected tapering on its massive US$85-billion-a-month bond and mortgage-linked securities purchases. This was certainly big tradable news as punters pushed up asset markets in the US and around the world. But will it change the thinking of policymakers in emerging markets, which have been especially hard hit since Fed chairman Ben Bernanke first mentioned tapering in late May?

Financial markets had a pleasant surprise this week when the US Federal Reserve held off its widely expected tapering on its massive US$85-billion-a-month bond and mortgage-linked securities purchases. This was certainly big tradable news as punters pushed up asset markets in the US and around the world. But will it change the thinking of policymakers in emerging markets, which have been especially hard hit since Fed chairman Ben Bernanke first mentioned tapering in late May?

Despite the economic downturn and falling currencies, developing markets are much better prepared and in more robust shape today than they were when they headed into the Asian financial crisis more than a decade ago. Their leaders, regulators and bankers have demanded clarity about the timing and pace of tapering but, by and large, most are making adjustments to a world in which the easy money of the last few years created by the US Fed's extraordinary programme of quantitative easing will be a thing of the past. After all, if not now, tapering still has to start sometime, with some experts predicting the beginning date likely to be in December or early next year.

Keep in mind that economies in Asia will still benefit from Japan's own massive quantitative easing while the European Central Bank and the Bank of England will continue their highly accommodating monetary policy in the conceivable future.

Talks of tapering have certainly caused massive capital outflows from the emerging markets as they are repatriated back to the US to seek higher and more profitable yields. But the equity and currency plunges have stabilised and in many emerging markets, the down trends have even reversed since late August. The real problems such markets face lie deeper than the threat of tapering.

Fundamentals have deteriorated in many developing economies as the easy money has shielded them from the Western economic meltdown, while weakening incentives to introduce meaningful structural reforms. China and Northeast Asian countries such as South Korea have worryingly high debt levels while countries such as India and Indonesia have large trade deficits. The delay in tapering is certainly a positive for these economies, but only for a short while.

QE is not a magic bullet but a dangerous drug. To let sustainable growth take off, those economies must introduce structural reforms to enhance productivity in a post-QE world.