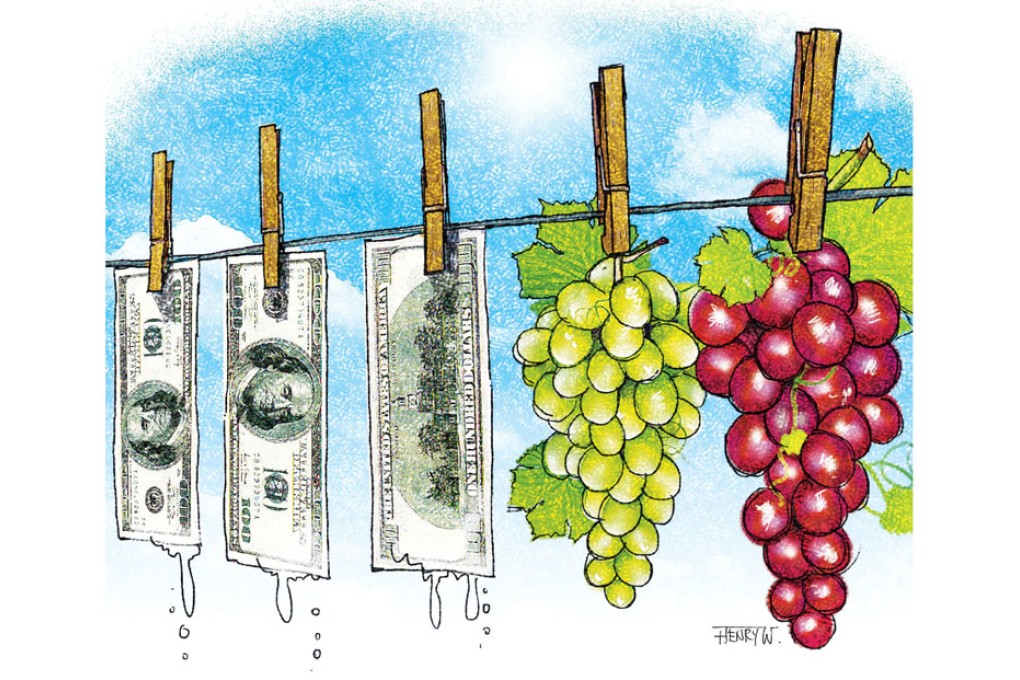

Money laundering taints wine trade

Avi Jorisch says while vineyards in France are favoured investments for Chinese and Russian money launderers, it's only the tip of the iceberg in terms of trade-based 'dirty money' schemes

Bucolic regions in the south of France represent the newest frontier for law enforcement and intelligence officials searching for dirty funds. Since 2008, thousands of people with alleged criminal connections have reportedly arrived in southwest France from eastern Europe, Hong Kong and mainland China to snap up vineyards to launder their money. European and Asian officials must take steps and curb this trend, including establishing trade transparency units to combat trade fraud.

In its latest annual report, the French anti-money-laundering unit, Tracfin, singled out Chinese, Russians and Ukrainians who buy vineyards, voicing concern that they might be using this type of investment to clean their ill-gotten gains. According to wine analysts, Chinese purchasers are one of the largest groups of vineyard owners in France and have been purchasing so many estates in the Bordeaux region that the local Chamber of Commerce reportedly has a help desk specifically for them.

Chinese nationals own as many as 50 wine estates and vineyards in the region, and there are reports of Chinese purchases in Burgundy. Russian investors are following suit, but according to wine experts, they prefer the Cognac region.

Prospective vineyard owners in France [are] offering to pay in cash, which should throw up a red flag

Global Financial Integrity, a respected organisation in Washington that monitors money laundering, reports a significant amount of illicit money leaving China and Russia, which partially explains these types of investments. According to its estimates, between 2000 and 2011 nearly US$4 trillion left China's economy, principally for tax evasion purposes, and between 1994 and 2011 over US$200 billion flowed out of Russia.

The vast majority of this tainted money was moved using trade-based money laundering schemes. According to Global Financial Integrity, developing countries are losing about US$100 billion every year to trade mispricing, which represents approximately 4.4 per cent of the developing world's total government revenue.

Typically, trade-based money laundering schemes involve invoice fraud and trade manipulation, principally via misrepresentation of price, quantity or quality of imports or exports. Specific tactics include over-invoicing, under-invoicing, double invoicing, and false invoicing. With these methods, large amounts of money can be moved while avoiding taxes, tariffs and customs duties, greatly complicating law enforcement efforts to follow the financial trail.

Purchasing vineyards is an excellent method to launder money. Reports have emerged of prospective vineyard owners in France offering to pay in cash, which should throw up a red flag. Moreover, the price of wine is never fixed; it is easy to over- or under-invoice. Paying in cash is not atypical; and perhaps best of all, it has all the trappings of high society.

According to Tracfin, foreign investors are buying wineries through multiple holding companies and complex legal structures involving tax havens and jurisdictions known for money-laundering. Often a legal French company is established whose shareholders include foreign shell companies, making it almost impossible to determine who actually owns the company or what the source of their money is.