Empress Dowager Cixi gets a makeover - regardless of the facts

Angelo Paratico says Jung Chang's book praising Empress Dowager Cixi as a reformer glosses over the fact that she was self-serving and ruthless

Yeung Kui-wan, a native of Dongguan but raised in Hong Kong, was a close collaborator of Sun Yat-sen, a great intellectual and a great patriot. He was shot at his Hong Kong home on January 10, 1901 by hitmen sent by the Qing government headed by Empress Dowager Cixi. He died in hospital the next day.

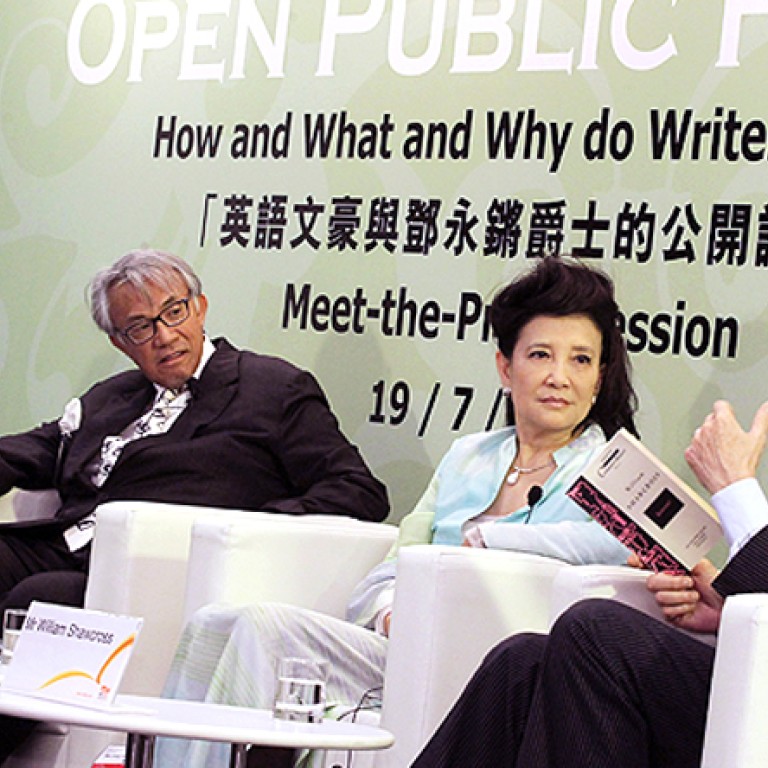

Yeung's name and the image of his grave in Happy Valley came to mind while reading Jung Chang's new book, , which has received glowing reviews all over the English-speaking world. The author is in Hong Kong this week to speak at the Foreign Correspondents' Club and the Asia Society.

Niccolò Machiavelli, the author of , wrote five centuries ago: "The tragedy of mankind is that we cannot find a man completely good or a man completely bad." Jung Chang, by her own admission, fell in love with her character and clearly decided to excuse all her crimes, praising Cixi's mettle and blind nationalism. With Hong Kong being a product of history, and history of a particular kind, clever distortions should not be welcomed.

Sun Yat-sen and Kang Youwei - a revolutionary thinker who saw the beheading, on Cixi's command, of his brother and several other friends - were both in favour of a reformed monarchy, while Yeung Kui-wan was a republican to the core.

Does Chang's affection for Cixi stem from the fact that she was vilified by Chinese Communists? If so, then she ignores the fact that she had been hated even more by Republicans and the Nationalists.

The book is undoubtedly well-written, both engaging and well structured, but it reads to me more like an apologia - in the classical sense of the term.

Historical facts seem to have been used only when they were useful and tossed away when they contradict the main theme of her work; that the heretofore-vilified Cixi had been a brave and forward-thinking reformer.

Chang has to jump through hoops to justify Cixi's actions and decisions. Cixi, it must be remembered, staged a coup d'état. She then clung to power through corruption and death threats. When her nephew, the emperor Guangxu, acted independently, aided by some forward-thinking reformists, she had them arrested and executed. Chang's justification for her behaviour was that they were planning to kill her: as well they might have been, given that she was, by the standards of the time, committing high treason.

It may be fashionable today to create a feminist heroine out of thin air, even if in fact there was none. Cixi was not a reformer - at least not in a way that mattered - and she could not have been one, either by instinct or education. Her hold on power was illegal and therefore shaky, so she was left with no choice but to surround herself with rabid and corrupt conservatives and listen to eunuchs - all people unable to offer dissenting voices to her suicidal and self-serving policies.

If there is a lesson to learn out of this fictional character created by Jung Chang, it is that a ruler, no matter woman or man, should embrace reforms put forward by younger people, or at least openly discuss them. Otherwise, being a reformist at heart - as Jung Chang tells us she was - will not change or improve the conditions of a country.