China extends its censorship reach

Paul Letters says China is expanding its influence in the developing world through a network of state-sponsored media that is giving global reach to communist party censorship

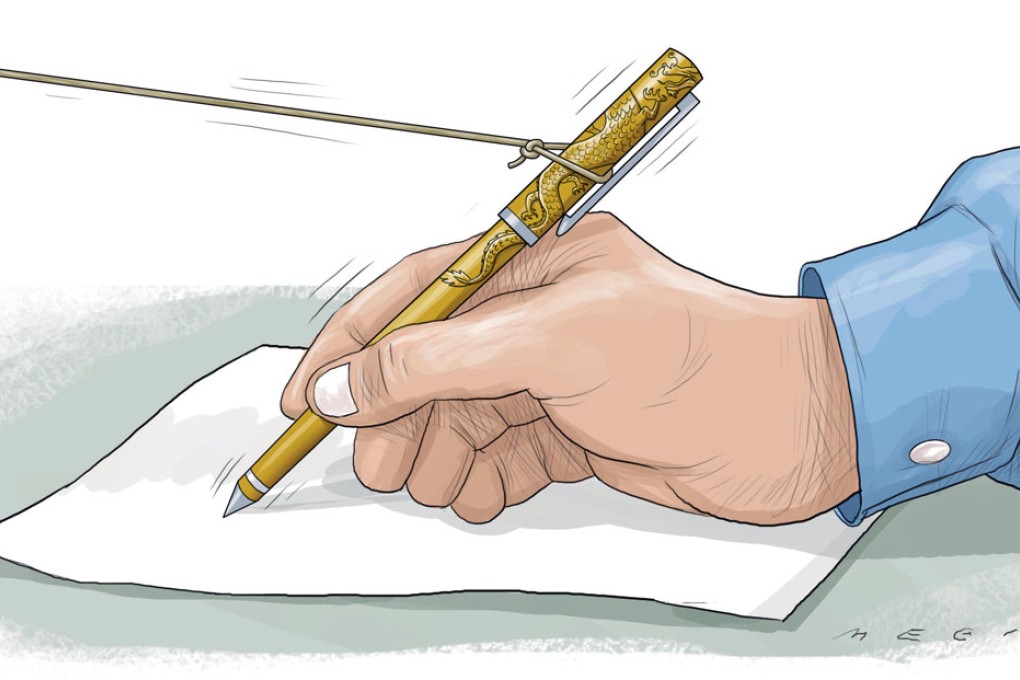

A recent report entitled "The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship" criticised the growing global reach of China's censorship and its unrestrained investment aimed at spreading state-sponsored media abroad.

The report, by the US government-funded National Endowment for Democracy, asserts that China's "efforts to influence reporting by foreign and overseas Chinese news outlets have intensified and expanded over the past five years", and points to a set of targets internally labelled "the five poisonous groups": Tibetans, Uygurs, the Falun Gong, Chinese democracy activists, and Taiwanese separatists.

Foreign correspondents' attempts to scrutinise issues such as party leaders' finances, Aids compensation, land disputes and environmental pollution have also encountered well-documented interference, from visa denials to cyberattacks against Western news organisations. China's array of economic carrots and political sticks, utilised across the globe, have now been exposed under one light.

Chinese authorities offer free editorial content to any cash-strapped news organisations

In recent years, the state-owned China Daily has paid for news pages - faintly labelled "advertisement" - within publications such as The Washington Post and The New York Times. It has launched a US edition (2009), a European weekly (2010) and an African edition (2012). But in Europe and North America, China Daily - and the new CCTV bureau in Washington - will not sway the mainstream news conversation. In the developed world, China has never looked like superseding American soft power. However, in vast tracts of the developing world China is making its mark. Media organisations there rely on foreign sources, so why not China, the world's leading developing nation?

Chinese authorities offer free editorial content to any cash-strapped news organisations seeking to avoid the cost of stationing correspondents in China and even fly their journalists to Beijing for all-expenses-paid training. In parts of Asia, Latin America and Africa, China has invested heavily in various economic sectors and is now buying shares in the media.

In South Africa, Beijing has bought major stakes in satellite television provider TopTV, and in Independent News and Media, a powerful newspaper group.

A show of goodwill often helps. In Zimbabwe earlier this year, CCTV provided President Robert Mugabe's state-monopoly television ZBC with new equipment - including giant city-centre screens - to broadcast his election campaign rallies. In return, ZBC has agreed to air CCTV news bulletins. In Cuba - China's biggest trading partner in the Caribbean and a leader in presenting an alternative world view to that of the US - Chinese companies have modernised Soviet-era infrastructure, and CCTV is replacing Russia's long-standing dominance in television programming.

Western media companies blanket the globe with a Western news agenda and often project an anti-China bias. The 2012 opening of CCTV's Africa centre in Nairobi is both an arm of China's broader expansion of influence in Africa and a step towards confronting Western outlets on the world stage. CCTV news scripts are skewed to adulate China's aid and trade in Africa and to avoid critical reporting of Chinese affairs. Reports of Zambian mine workers rallying against unfair treatment from their Chinese bosses is a story you won't see on CCTV. Another is the illegal slaughter of African elephants, driven by Chinese demand for ivory.