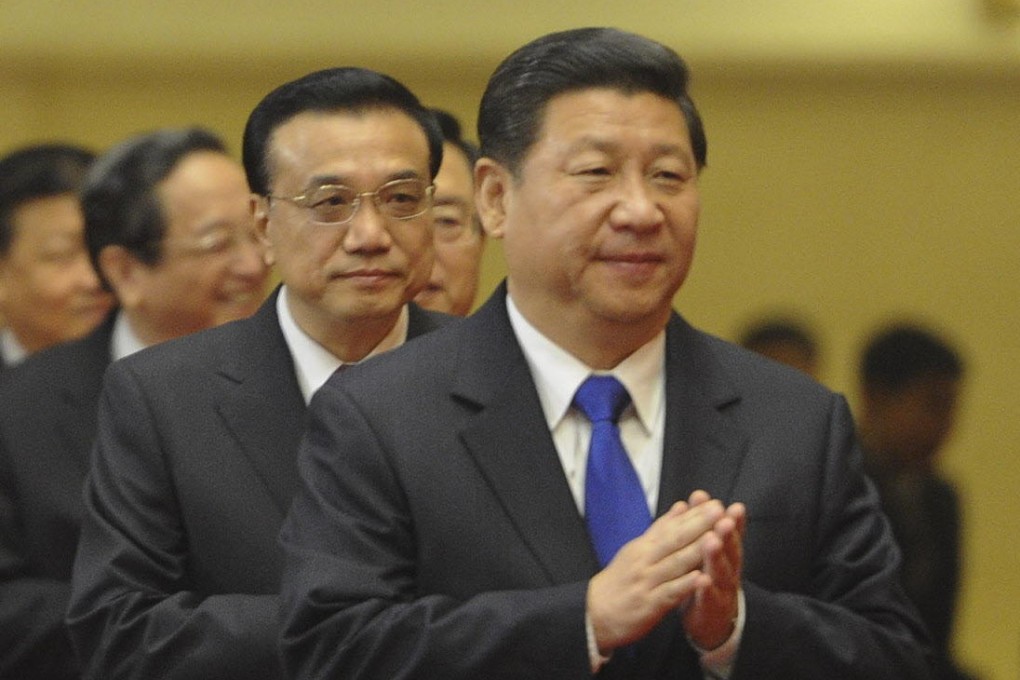

Opinion | Xi moves closer to becoming another paramount leader

State leaders may have stumbled in roll-out of plenum measures, but president's ascent is undeniable as Premier Li takes back seat

The disappointment among business leaders, analysts and even junior mainland officials was almost palpable on Tuesday after Communist Party leaders emerged from a secretive four-day meeting and outlined their much-anticipated plans to move the country forward.

The communiqué from the third plenum of the party's 18th Central Committee was full of lofty slogans including a vow to allow the market to have "a decisive role" in the economy and to achieve "decisive results" by the end of the decade.

But the document's vague language fell short of expectations driven up by the state media and senior leaders, such as Yu Zhengsheng , the No4 member of the Politburo Standing Committee, who predicted "unprecedented reforms". Many had drawn parallels to the landmark third plenum in 1978, when Deng Xiaoping laid the groundwork for the country's decades-long economic boom.

The next day, stock markets on the mainland, Hong Kong and elsewhere in Asia fell sharply. The declines continued on Thursday.

State leaders were perplexed and worried by the reaction, as plenum communiqués are about announcing a consensus and not meant to spell out specific reforms. Indeed, the 1978 document provided no grand blueprint and didn't even mention the words market economy. Concrete measures that would give rise to the so-called socialist market economy came months or even years later.

The country's leaders tend to forget they now control the world's second-largest economy. Their policy announcements can have far-reaching implications for the rest of the world. High-sounding slogans without specifics no longer cut it.