Hong Kong must get a real conversation going if it wants democracy

Jasper Tsang tells how his involvement in the early days of democratisation in Hong Kong has impressed on him the importance of dialogue across the political spectrum, particularly now

I never intended to become a politician. I never wanted to get involved in politics when I was in school. I went to the University of Hong Kong during the late 1960s, the years of Hong Kong's riots. The Cultural Revolution was in full swing and there were violent student movements worldwide. But even then, I was never a student activist.

When I finished my degree, I went to teach in a leftist school. But even then I had not intended to get involved in politics. I went to teach for practical, rather than ideological, reasons as I wanted to become a scientist and work in China. But the Cultural Revolution was going on. I never expected it to last 10 years. I was 30 when it was over and had forgotten almost everything I learned at university.

A few years later, China and Britain started to talk about Hong Kong's return to China in 1997, which led to the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984. Extensive consultation exercises followed and many were involved.

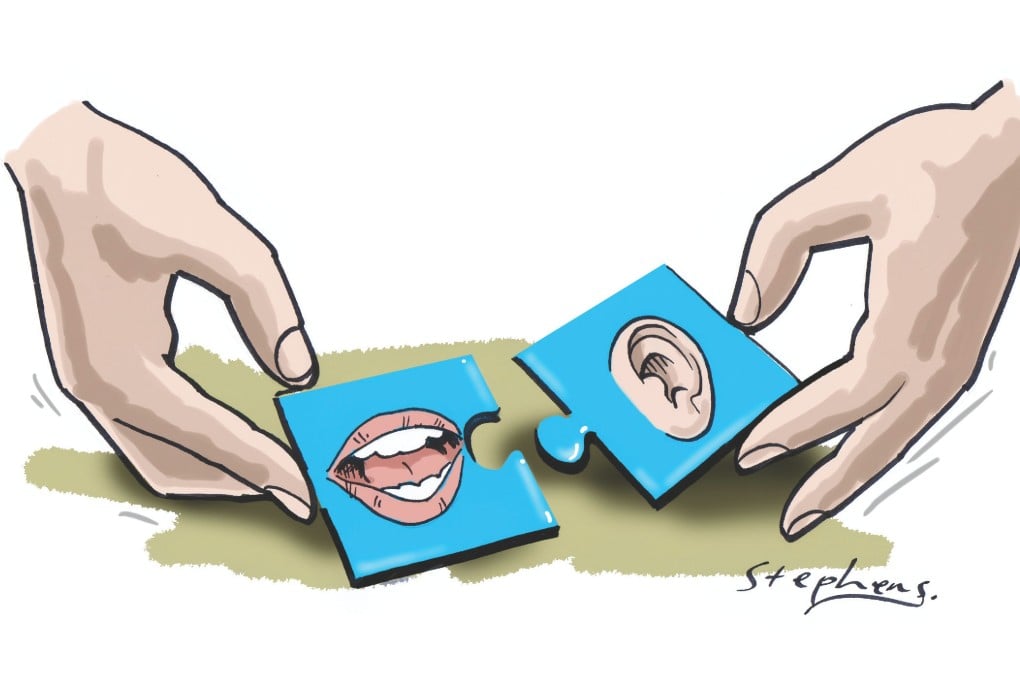

I still remember when we could sit in roundtable discussions with people from different backgrounds and political beliefs, and officials from Beijing came and listened. There were democrats, businesspeople and moderates. I took part and, looking back, I'd say those were the best years of dialogue between Hong Kong people, Beijing and consultations with the public. We were able to narrow the gap gradually and we moved towards a consensus.

All of us believed that for "one country, two systems" to work, we must have a democratic system. That was the first consensus. At the same time, most of us believed we should move towards that goal in steps; we believed the benefits of the existing systems should be kept. Thus, we were able to narrow our gap and I'd say that a lot of the proposals and views of those taking part in the public discussions were incorporated in the final draft of the Basic Law.

Four years and eight months later, and suddenly, there was June 4 and everything stopped. And all those who were working together with Beijing to bring democracy to Hong Kong after 1997 suddenly turned against Beijing. And the Chinese officials who had come to Hong Kong regularly and talked to activists suddenly began to regard them as subversive. For the first time, Beijing called Hong Kong a base to subvert China. Of course, there were one million people marching and shouting slogans against the Chinese government. When the dust settled in Beijing, we became divided. Two camps emerged. If you're a politician in Hong Kong, you must belong to one of the two camps: you're either pro-Beijing or pro-democracy. That is the unfortunate situation that came from June 4 and has continued until today.

The first direct election for the Legislative Council took place in 1991, two years after Tiananmen. Three candidates with a pro-Beijing background stood. They all lost. All the headlines said that being a friend of Beijing was a kiss of death; no one who's seen to be a friend of Beijing could be trusted by Hong Kong people and they would not stand a chance in elections. That was the general belief.