News of a children's commission will bring good cheer to Hong Kong

Grenville Cross says in a city with more than 281,000 children in poverty, the chief executive should announce in his policy address the set-up of a commission to advocate on their behalf

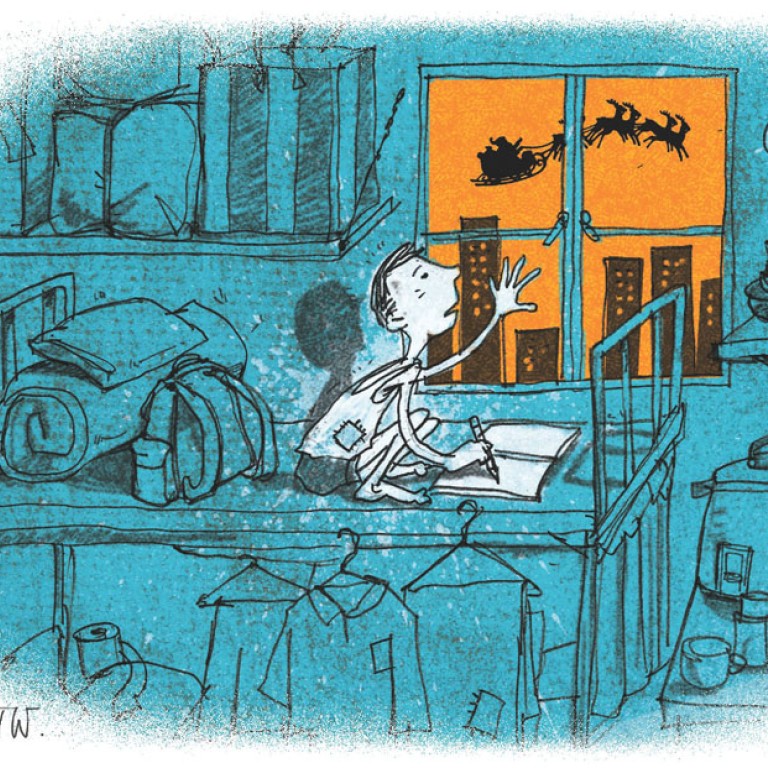

God bless us, every one," said Tiny Tim, in . Although Christmas is a time of joy and giving, there are many people in Hong Kong who will find it hard to possess the seasonal spirit. Poverty, unfortunately, is a fact of life in many of the city's households.

Hong Kong is, of course, a hugely rich city. In January, the government announced that its fiscal reserve had reached HK$709.1 billion by the end of last year. Money is not a problem, although allocation is, and the government has ruled out using its resources to lift people out of poverty, claiming that funds must be distributed prudently.

However, the scale of poverty is truly shocking. Last year, for example, in its poverty report for 2003 to 2012, Oxfam Hong Kong found that the situation of poor working families had deteriorated over the period, with one in every six people living in poverty. Poor families remained trapped in poverty, despite some members having jobs, with the number of poor households standing at 400,000.

This year, the Commission on Poverty set the poverty line at half the median household income, before taxes and social benefits. About 1.3 million people, or roughly one in six of the population, are, therefore, below the poverty line.

Last month, moreover, researchers from Hong Kong's City University and England's Bristol University, based on a six-month study of 600 Hong Kong households and comprising 1,900 people, went even further than the commission. They reported that whereas 21 per cent of Hong Kong people were poor and 20 per cent were vulnerable, defined as being on the edge of poverty, the situation of the young was worse, with 27 per cent of children being deemed poor, and 22 per cent considered vulnerable.

Some families were found to be experiencing difficulty in providing three square meals a day, in buying fresh fruit and vegetables, in participating in public holidays, and in arranging extracurricular activities for their children.

The Hong Kong Institute of Education also recently noted that the distinction between poverty and severe poverty is often overlooked by the government, and that more than 40 per cent of people living in severe poverty now have to survive on less than HK$120 a day. Given that groceries are estimated to account for over 50 per cent of expenditure in some of the poorest households, there is precious little left for basic child welfare, let alone education.

According to the Society for Community Organisation, many youngsters have to do their homework on beds in tiny flats, cannot afford to participate in some school-related activities and have to undertake menial jobs after school to help their parents make ends meet.

Too many children now find themselves trapped in a cycle of poverty, with little hope of escape. They are missing out on the chance to realise their potential, which, in an affluent society, is intolerable. After all, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which applies to Hong Kong, enshrines the child's right to development, participation and survival, and all these rights must be fully honoured. This, in turn, requires the creation of a dedicated children's commission, to act as an agent of change and, where necessary, of protest.

In January, when the Society for Community Organisation with other non-governmental organisations made their submission to the UN on children's issues, by way of comment on the government's report on the implementation of the UN convention, they highlighted the importance of a comprehensive and integrated child policy, which included a centralised body to safeguard children's rights.

They revealed that, due to financial difficulty, 60 per cent of underprivileged children do not see a doctor when sick and that 20,000 children live in inadequate housing, and that about 281,900 children are now living in poverty.

Reading this in Geneva, the UN officials must have felt incredulity, given that Hong Kong is one of the world's richest cities.

However, all is not lost.

Last month, the Legislative Council voted unanimously, just as it had in 2007, in support of Dr Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung's motion to establish an independent children's commission, to advocate the rights of the child, to give children a voice in their own affairs, and to ensure they receive a fair deal.

Whereas the administration of the former chief executive, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, ignored the 2007 vote, his successor, Leung Chun-ying, who has acknowledged that "the problem in Hong Kong is poverty", must avoid making the same mistake. Leung must heed this latest vote and include establishing a children's commission in his policy address next month.

Children's commissions are already functioning effectively in many places, including Australia, Britain and Canada. The Leung administration, which has already done much for the underprivileged, will earn lasting praise if it now embraces this proposal.

Hong Kong already has in place a youth commission, an equal opportunities commission, an elderly commission and a women's commission, and it beggars belief that children, as the most vulnerable group of all, have been denied a dedicated body of their own.

No cogent reasons have ever been given for this omission, but myopia and timidity will, undoubtedly, have played their part.

Quite clearly, a children's commission cannot possibly solve all the problems children face, let alone poverty, but that is not the point. A commission will stand up for children, argue their corner and campaign for their rights. Action is needed, and time is running out.

Although the announcement of a children's commission, in the policy address on January 15, will come too late to be of any cheer at Christmastime, it will at least ensure that the Year of the Horse gets off to a more hopeful start.