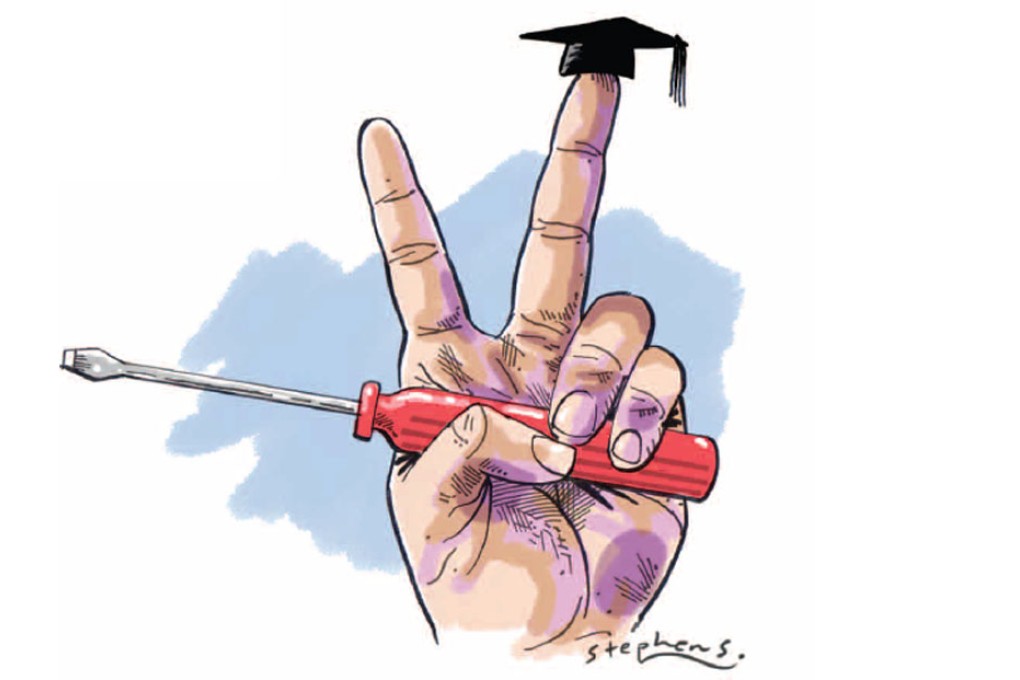

Time to move past stigma of vocational education

David Lim welcomes the recent recognition of the role vocational education can play to provide meaningful work for Hong Kong's young people, while catering to the needs of the economy

Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying pointed out, in his policy address, the importance of vocational education and training for Hong Kong. He made the obvious but often forgotten point that academic education is not for everyone and more guidance should be given to the young in their choice of careers. Accordingly, it will take a number of initiatives to promote it, with the Vocational Training Council playing a significant role.

This is welcome, and some would say about time too, because vocational education and training has too often played second fiddle to academic education, and the role of the council in training young Hongkongers has never been properly recognised. It is also consistent with the central theme of Leung's address to help the poor because many students of vocational education and training come from poorer families.

An efficient labour force must consist of a number of related parts; one will not function well without the other. Vocational education and training is integral to this. The growth of many economies has been hampered by the absence of such skills. In Australia and Canada, many university graduates now enrol in vocational institutions to improve their employability.

The relative importance of the parts must be consistent with the economy's requirements. In the poorest economies, the labour force structure resembles a pyramid, with a large number of workers with basic literacy and technical skills, and low incomes, at the base. In richer economies, where repetitive, routine, low-skilled work is done by machines, the structure is more like a diamond. The demand for workers with low skills is small; it is large for workers with higher skills on good pay. In Hong Kong, the structure across all age groups resembles an hour glass, especially so among the 15-24 age group.

Vocational education and training is also not appreciated because of its stigma. People in Hong Kong prefer academic education, seeing vocational education and training as a last resort that is good enough only for "academic failures", which is reinforced by its traditional omission from mainstream education.

There is a historical reason for this. Workers with vocational education and training skills were produced by the apprenticeship system, where apprentices, usually working-class children, learned skills in artisan and industrial trades under master craftsmen. But this system could not produce the large numbers of workers needed by the Industrial Revolution and, in Britain, vocational education and training schools were set up as an alternative to provide working-class children with basic technical skills. These schools existed side by side with highly exclusive schools for children of the upper class, and general schools for children of the middle class to equip them for civil service jobs.

As vocational education and training originated as the main avenue for working-class youth, it acquired a stigma among those who aspired to move out of that class. It fell further from favour with the introduction of egalitarian education, as its narrow emphasis limited opportunities for future access to higher education and occupational positions, and reproduced the very social and occupational stratifications that spawned it. The latest data from Unesco shows a consistent fall worldwide in the share of vocational education and training in total secondary education enrolment , from 24 per cent in1950 to 11 per cent in 2010.