The unknowns in China's great urban change

Kam Wing Chan says China's bold new urbanisation plan raises many questions, not least how the increased social costs will be funded and whether the focus on small cities can achieve the desired result

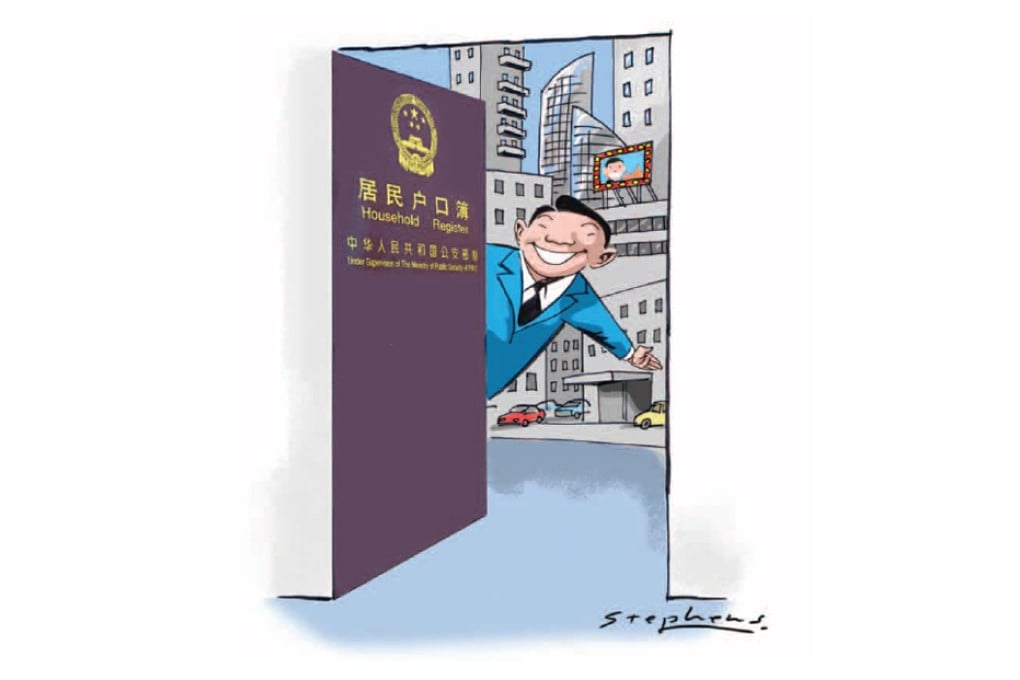

After more than a decade of mostly empty talk, China has finally announced a bold move to grant urban hukou status to 100 million people by 2020. The target is a major component of China's new urbanisation plan, which represents a significant commitment towards achieving genuine urbanisation.

In the past two to three years, urbanisation has been refashioned to drive growth and remake the Chinese economy in the coming decades. To accomplish that, it is essential to allow migrants living in cities to have a full urban hukou, and thus be able to access basic urban services.

For the past three decades, "urbanisation" in China has often meant allowing millions to move into cities without giving them an urban hukou, thereby excluding them from using social services. In recent years, it has also meant local governments borrowing huge amounts of money against land (much of it expropriated from rural people) to build infrastructure, some necessary, some not. Impressive GDP growth is generated, some of it suspicious.

More dangerously, such urbanisation has led to mass environmental damage and social unrest. Critics have dubbed this China's new Great Leap Forward.

About two years ago, in response to widespread criticism, then vice-premier Li Keqiang began to push for a "new-style" urbanisation, focusing on the human aspects, rather than construction, and emphasising growth in urban household incomes rather than local-government investment spending on buildings.

At the third plenum last November, it was recognised that China's dual rural-urban social structure, set up in the 1950s, remains a major obstacle to development. The system of hukou, or household registration permits, for rural and urban residents separates them into two disparate social, economic and political spheres, resulting in many problems. Recognition of this opens up the possibility for a bolder and more innovative strategy to guide the latest urbanisation drive. For a more holistic, human-centred approach to succeed, three interrelated reforms are crucial. First, hukou reform, to enable rural migrants to build more secure lives for themselves and their families in the cities and towns where they now live.