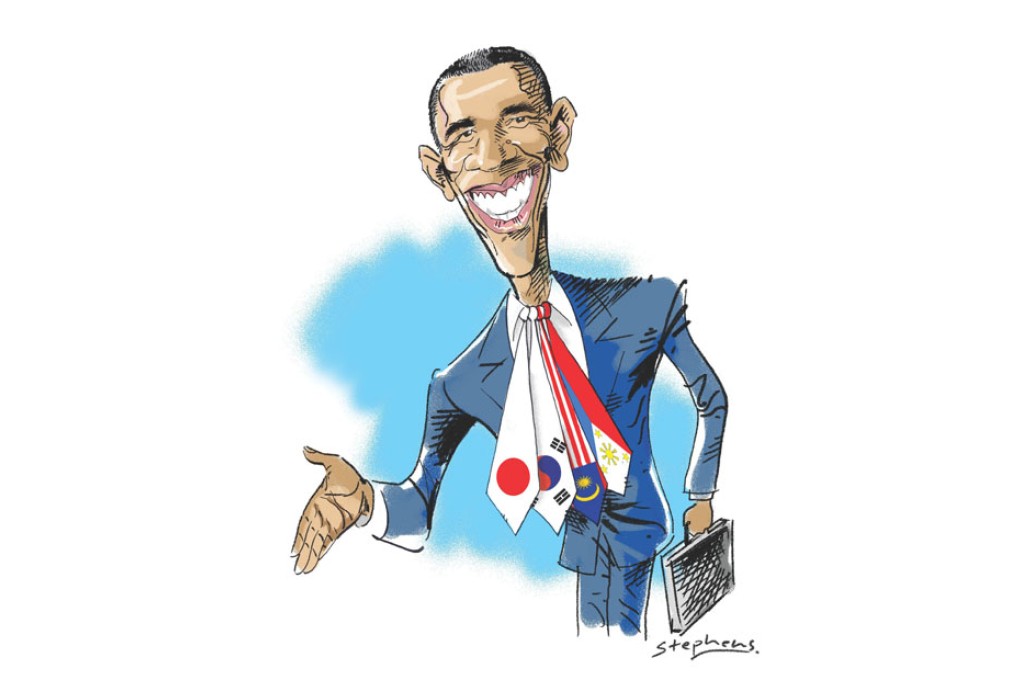

Obama's quest to cement Asian ties

Andrew Hammond says following an aborted visit last year, Obama is certain to redouble efforts during his visit to the region to reassure allies that the US pivot is very much alive

Barack Obama touches down in Japan on Wednesday to start an important week-long trip that will also take in three other countries: South Korea, Malaysia and the Philippines. His overriding goal will be to reassure these allies about enduring US commitments, while sending a clear message to neighbouring states, including China, about US intent to maintain its Asia-Pacific pivot.

This is a simple but crucial message at a time of significant geopolitical turbulence and tension - both in the region and beyond. The trip, for instance, comes when US foreign policy attention remains diverted by events in Ukraine, which many in Asia are also watching closely as a potential signal for how Washington might respond to any future Chinese belligerence.

However, the need for US reassurance comes in a broader context of the postponement of Obama's planned Asian trip last autumn during the US government shutdown. There has also been substantial regional change in the past 18 months, which has seen a once-in-a-generation transition of leadership in China, the subsequent rise of a more assertive Beijing, plus the election of the conservative, nationalist Japanese prime minister, Shinzo Abe.

Careful management of deep-seated problems is key to realising US objectives

The fluid, unpredictable environment this has generated has caused continual headaches for Washington since Obama was re-elected in 2012.

Indeed, the president currently faces the most significant array of obstacles towards realising his goals in the Asia-Pacific region than at any other time during his presidency. For instance, progress towards securing the landmark Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement may be stalling, despite Washington's ambition to secure a deal this year featuring at least 12 countries that collectively account for around 40 per cent of the world's gross domestic product.

Moreover, there are significant bilateral tensions, including between Japan and South Korea (Washington's two leading regional allies), which Obama is fire-fighting. Only last month, he made some potentially important progress in this regard at the Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague, where a three-way meeting with Abe and South Korean President Park Geun-hye was the first high-level contact between the countries for months. As in much of East Asia, underlying bilateral tensions between Seoul and Tokyo reflect the legacy of a troubled past. In this instance, significant distrust and anger remains from the period when Korea was under Japanese rule, including as an annexed colony from 1910 to 1945.

These issues have been given new impetus by the election of Abe, whose conservative, nationalist agenda emphasises greater pride in the country's past, and also overturn remaining legal underpinnings of the country's post-second-world-war pacifist security identity, so that it can become more actively engaged internationally. While this is all largely aimed at countering Beijing's growing power, it has alarmed Seoul, too.