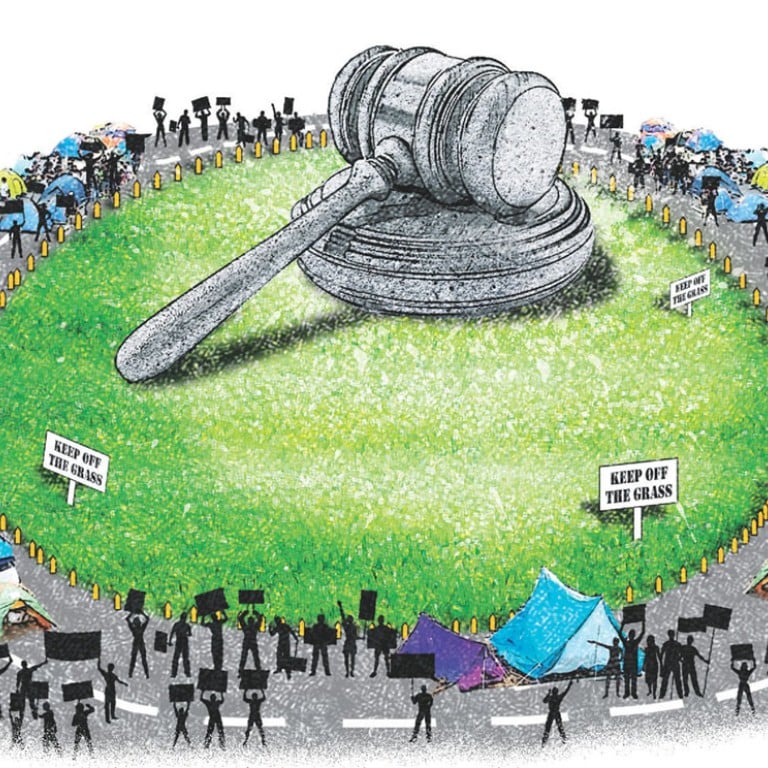

Occupy protests breaking law, but not undermining Hong Kong's rule of law

Michael C. Davis says while Occupy protesters are clearly breaking the law, they are arguably not undermining the rule of law through their peaceful civil disobedience campaign

A small group of lawyers has added to the chorus of establishment figures denouncing the Occupy movement as undermining the rule of law. Are they right?

As the protests stretch well into their second month, we are hearing increasing calls for them to end. Some of these are calls of prudence, suggesting withdrawal and alternative strategies to promote the protesters' cause. On the other side, officials and now a small group of establishment lawyers have accused protesters engaged in civil disobedience of undermining the rule of law.

Do protesters using civil disobedience to promote democracy and better secure Hong Kong's core values pose the risks to the rule of law that officials and pro-government lawyers claim?

It is important here to distinguish between breaking the law and undermining the rule of law. The non-violent protesters have clearly broken the law by not complying with the Public Order Ordinance and, further, by not clearing those areas covered by court orders. Both are purposeful law-breaking in furtherance of a non-violent civil disobedience campaign. We should bear in mind that civil disobedience by definition involves breaking the law in support of a higher ideal that is the aim of the civil disobedience campaign.

Some argue that the anti-Occupy demonstrators who physically attack protest sites are comparable, but these attacks appear to have been neither civil disobedience nor non-violent. Clearly, the scales shift heavily against any protesters on the street employing violence and the police would be duty-bound to protect other protesters from such violent attacks.

The police also have a duty to investigate fully the widely publicised alleged attack by a group of officers on an already subdued and handcuffed protester.

Rampant law-breaking in a society may sometimes contribute to undermining the rule of law, in that it may create a situation of distrust towards lawful authority, degrading general adherence to the law. Examples might include rampant corruption, cronyism or high levels of violent crime and lawlessness.

But not all law-breaking effectively undermines the rule of law. The case for civil disobedience not doing so may be especially high when the civil disobedience itself is non-violent and reasonably confined, and is a protest against the government undermining democracy or the rule of law.

A more direct threat to the rule of law typically comes from government. As the term "rule of law" suggests, the ruler may more readily put the rule of law in jeopardy. The commitment of the rule of law is that nobody is above the law and everyone is subject to the law applied in the ordinary manner. Further definitional refinement may include notions of justice, adherence to human rights and so on.

The white paper and the National People's Congress Standing Committee decision call the government's adherence to basic principles of the rule of law into question. The white paper, claiming that sole authority over the Basic Law resides in the central government and comprehensive jurisdiction in the NPC Standing Committee, appears to abandon Hong Kong's internationally guaranteed "high degree of autonomy" and put the Standing Committee above the law.

Why should the Basic Law make distinctions between matters of central authority and matters of autonomy if all are matters of central authority? The Standing Committee decision makes mincemeat of the promised "universal suffrage", thus further degrading the human rights guarantees in the Basic Law.

By putting the Standing Committee above the law and redefining basic human rights guarantees in an unrecognisable manner, the State Council and the Standing Committee have put Hong Kong's high degree of autonomy and rule of law in jeopardy. The failure of the local government to guard Hong Kong's high degree of autonomy and its seemingly complicit role in the Standing Committee's decision implicates it as well.

The pro-democracy civil disobedience campaign aims to correct this situation by putting in place a government that will better represent Hong Kong people. Such a government may be more responsive to local concerns and better guard Hong Kong's high level of autonomy. Beijing and Hong Kong officials might be persuaded that such a circumstance may be more favourable in an open society such as Hong Kong than the contentious situation their policies now encourage.

Even the Hong Kong Bar Association recently acknowledged that there is a division of opinion among jurists over the legitimacy of civil disobedience strategies that aim to support such basic human rights. Judges may sometimes be reluctant to strictly enforce laws against such non-violent protests due to regard for competing free speech concerns. Academic debates on this have identified the lack of democracy as one of the conditions generally thought to support a degree of legitimacy for civil disobedience.

So, overall, there is a good case to argue that the two recent Beijing decisions and related policies present a greater threat to the rule of law than does the civil disobedience campaign. Is either one desirable? Of course not. But when protests are a product of poorly considered government policies, the way out is for the government to change the policies.

If pro-government lawyers and politicians want to do a special service for our community, they could accomplish much more by using their access to Beijing and Hong Kong government leaders to better convey the concerns so eloquently raised by Hong Kong's young people.

As a professor who teaches our young people about the foundations of our legal system, I have been amazed at how clearly our youth, even at the secondary school level, have appreciated the risks the recent Beijing white paper and the Standing Committee decision entail.

In this context, leadership by those in government, or if not, by those close to the government or Beijing, will be crucial to turn around the failed policies and better represent Hong Kong concerns. The lack of such leadership vision explains a lot about the current impasse and threats to Hong Kong's rule of law.