Hong Kong needs a political solution, not a legal one, to Occupy protests

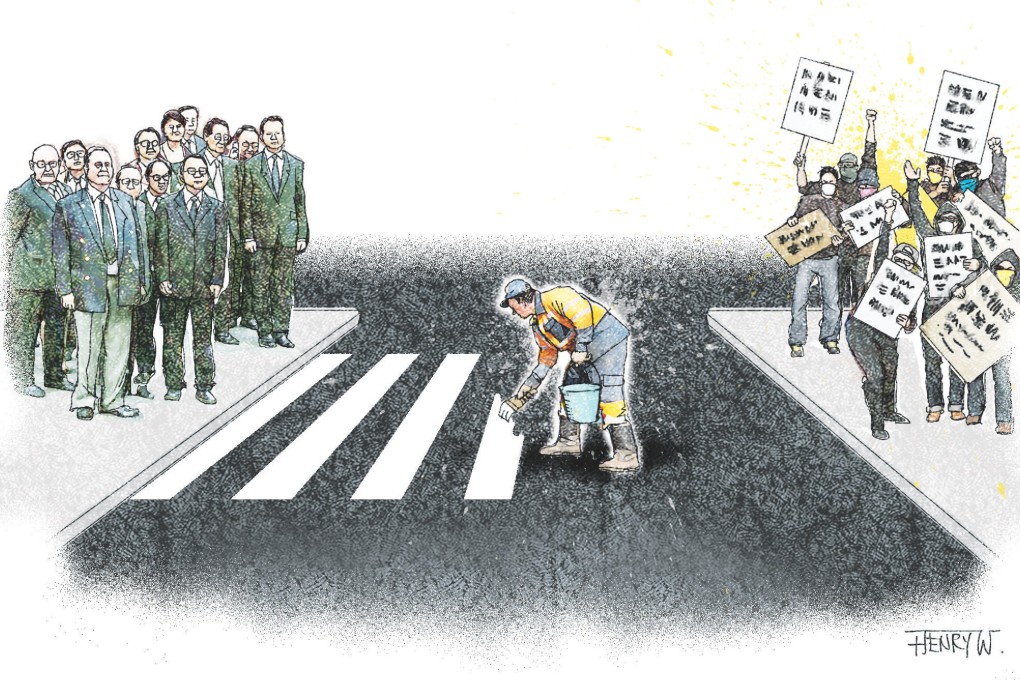

Stephanie Cheung says clearing the streets of protesters will only result in a hollow victory for the government. Rather, it should bridge the social divide by responding fully to the concerns raised

President Xi Jinping has made it clear that the buck stops with the chief executive for bringing the "umbrella movement" to a close. Chief Secretary Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has made it clear that there is to be no further room for negotiation with the students, while Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying has acknowledged that the Occupy protest is the biggest social movement Hong Kong has faced in its history.

With US President Barack Obama stating unequivocally that the US had no involvement in fostering the movement, blaming it on foreign instigation is no longer tenable. The government should at last face the fact that the movement is a social/political issue requiring a social/political solution, instead of pretending it is a law-and-order issue to be solved by the police, or a rule-of-law issue to be solved by the law courts.

The government has been playing the protest out like a court case, as it reckons that, on the one hand, by dragging it out, the movement will fizzle out naturally as support diminishes, while on the other, it always has the option of forcible eviction by the police. Either way, the government wins - or so it would seem.

However, a far-sighted government would realise that such an approach will lead to a pyrrhic victory.

In the 40-odd days of protests, only one formal meeting has taken place between government officials and the protesters, and that was at the request of the Federation of Students. The students have come up with lists of different demands, whereas the government declines negotiation. This is most frustrating, not only to the protesters, but also to the public, who have to suffer the consequences of this deadlock.

We need not take too literally the protesters' demands for a reversal of the electoral framework of August 31, and open nominations. Instead, we can be unified behind their cry for a more just society, where political power is better shared. We need to keep these youth engaged and motivated instead of alienating them and killing off their enthusiasm.