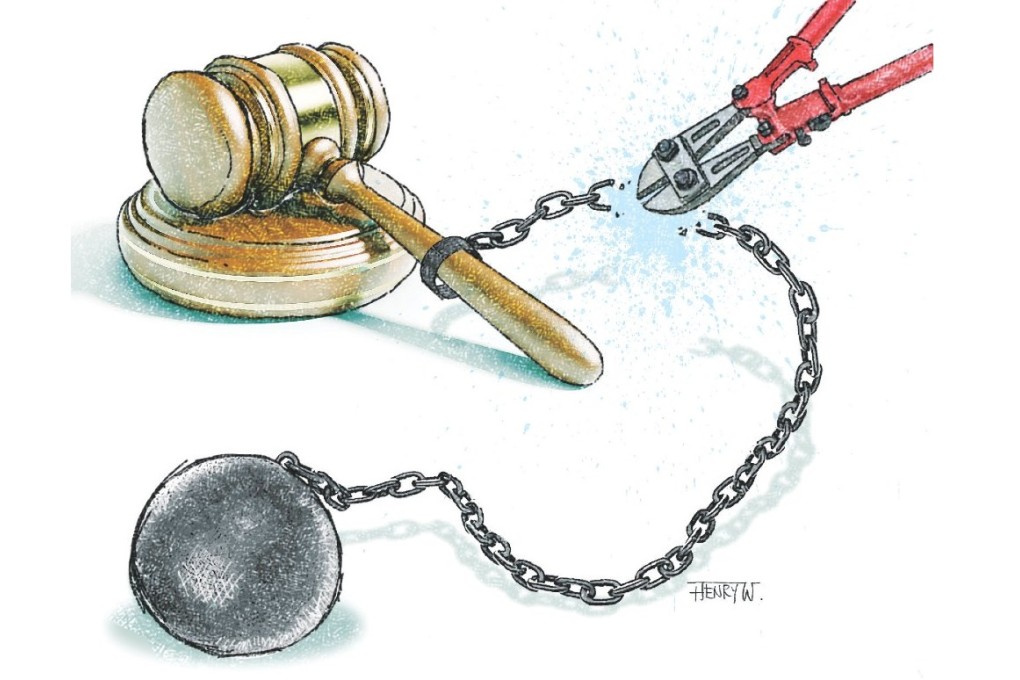

China needs a robust constitution with bite

Winston Mok says China's promised new era for the rule of law will help balance power at the local and provincial levels, reducing corruption and conflict, while boosting economic growth

More than three decades after the passing of its 1982 constitution, China is commemorating its first Constitution Day this week, heralding a new era for the rule of law. As argued by economist Friedrich Hayek, the market can only work effectively under the rule of law. Businesses and individuals will invest with confidence under known and clear rules, free from capricious government action.

According to the World Economic Forum, China has weak property rights and intellectual property protection, and even weaker investor and minority protection. While China's economy has enjoyed spectacular growth for decades, it may soon be trapped under a glass ceiling unless it makes the transition to a more rule-based economy.

China has been making practical steps to improve the rule by law. Local courts were made financially independent from local governments. Court administration has been streamlined and judges now have greater professional independence. At the recently concluded fourth plenum, China made the rule of law the new modus operandi for governance.

Beijing needs to look no further than Hong Kong as a model for legal reforms. Hong Kong is ranked fifth by the World Economic Forum in judicial independence, the highest in Asia. In fact, the city ranks among the world's top 10 in various indicators, from property rights (sixth) to investor protection (third).

But the rule of law has a much more fundamental meaning. Hayek defined it as the opposite of arbitrary government. In the report of the World Justice Project, mainland China is ranked very low on constrained government. To address this, the fourth plenum decisions outlined reforms in the legislature, executive and judiciary - including greater separation of the three.

On the mainland, the key checks on the government have been the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the National Audit Office. The legislature and the judiciary may become increasingly important balancing forces.

Local governments will be made more accountable, and are expected to govern in accordance with the law. In a nutshell, the age of local administrations interfering with the judiciary has passed, and the time of administrative power checked by the judiciary has come. Such a transition may hopefully be completed by the end of the decade - the time frame President Xi Jinping has set for the modernisation of governance.